'No plan' to address homelessness in Multnomah County, commissioner says

Commissioner Sharon Meieran thinks the lack of a cohesive governing body for the response to homelessness is hampering those efforts. She wants a major reset.

The issue of homelessness can be ideologically fraught; many people disagree on how best to address it. But perhaps most residents of Multnomah County can agree that however it's addressed here, it's not being done well. That's certainly the opinion of one county commissioner.

In the run-up to 2022 midterm election, many Portlanders received mailers from a well-heeled group called the "Portland Accountability PAC" laying out their preferred candidates for local office — Rene Gonzalez for Portland commissioner and Sharon Meieran for Multnomah County board chair.

The two candidates were linked by their comparatively tough rhetoric on addressing homelessness and crime in the greater Portland area — Gonzalez perhaps more so than Meieran due to his explicit focus on law and order.

Gonzalez went on to win his race against then-Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty. But Meieran, already a county commissioner, lost her race to fellow Commissioner Jessica Vega Pederson. Meieran remains on the county board, having first won election six years ago. Her current term ends in December 2024.

Meieran is actually Dr. Sharon Meieran. She's an ER doctor with degrees in economics and English, also receiving a law degree before going to medical school. She's served on several boards focused on medicine, opioid abuse and others.

Recently, The Story's Pat Dooris sat down with Meieran to discuss an editorial she wrote for the Oregonian in late April. In it, she celebrated the hiring of Dan Field as new director for the Joint Office of Homeless Services — the Multnomah County-helmed agency that's supposed to coordinate resources with the city of Portland.

But alongside that optimism, Meieran criticized how the response to homelessness is being handled in Multnomah County — backed by a budget in the hundreds of millions of dollars each year, much of it coming from taxpayers.

Meieran highlighted the human misery that the homelessness crisis perpetuates, for the unsheltered and sheltered alike, and local stakeholders that aren't sufficiently organized to address it.

Despite the existence of JOHS, Meieran says that there is no master plan to end homelessness in the greater Portland area — and it shows.

An imperfect union

So how can it be that there's no plan?

"That is a question that I ask frequently and put it in the op-ed, because what I've heard often is people saying that, 'I don't know what the plan is ... it's not communicated well,' and sort of foisting it onto communication," Meieran said. "But the reality is there's actually no plan, no overarching plan, and that is because there's no like cohesive, united governing body that is creating a plan."

If there is no plan and no coordination, Dooris asked, how will we ever know if we're making progress?

"That is a question I've been raising for quite a few years now, and that I really wanted to highlight in the op-ed, because we truly need outrage," Meieran replied. "We need pushing of our city and county now that we have new leadership at the county, now that we have a new director of Joint Office of Homeless Services. We have an opportunity to maybe reset, put these pieces together, but until now it's ... we haven't had the structure, the political will to combine forces, unite and create a common plan."

It's a case of one hand not knowing what the other is doing, Meieran described, between the county, city and nonprofits — and she's been trying to figure it all out since she first became commissioner six years ago.

"At first I thought there was a governing body, and then I thought the Joint Office of Homelessness was an actual joint office of homelessness between the city and county," Meieran said. "What I learned over time as I peeled back layers of the onion was that the joint office is actually now a county department exclusively, with no oversight or governance by the city.

"And so the city, we have an agreement — the city puts a whole bunch of money into the joint office, you know, they offer their ideas and try to work with the leadership of the county to see if their ideas can be can be implemented, but they have no say — they don't have the power over the joint office. And so for the past, for the six years prior to our former chair leaving, there's not been that desire to coordinate and collaborate, and it's not been a joint office — it has been the chair leading the joint office and directing all of that."

And the lack of coordination between the city and county has become more apparent within the past few months. When Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler succeeded in having his plan for large-scale sanctioned homeless camps adopted by the city council, he expected Multnomah County to pitch in to the tune of $21 million. The board of commissioners shot that idea down. Meanwhile, Portland will withhold $8 million that it would typically contribute to JOHS in order to put it toward those sanctioned camps.

For better or worse, JOHS is insulated from some of the big swings that come out of Portland city government. Portland's contribution is a drop in the bucket compared to the funding the office gets from Metro's Supportive Housing Services Tax.

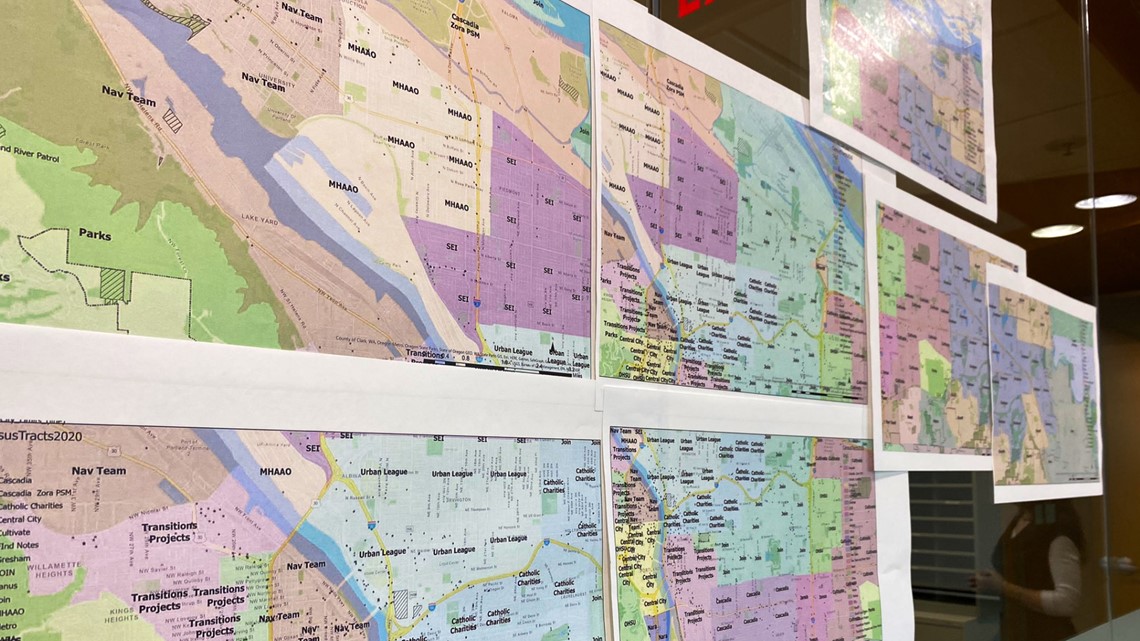

To be fair to JOHS, it has its fingers in a lot of pies. It supports a constellation of homeless shelters of all types throughout Multnomah County, plus rental assistance, eviction protection and rehousing programs, navigation services and outreach — much of this directly operated by a long list of different nonprofit providers that the department interfaces with.

Theoretically, the spectrum of services propped up by JOHS are supposed to meet people experiencing housing insecurity wherever they're at and help them back to stability in a way that's sustainable, which is pretty much what Meieran describes as being needed. But it's unclear to what extent they hang together.

And JOHS does track performance. It produces an annual report each fiscal year with outcomes from that year, in addition to quarterly performance data — like how many people have been moved into permanent housing and even how many of those have returned to the streets.

Despite all this, Meieran's perspective is that there is no clear-eyed assessment of what needs to be done for homelessness in the Portland area and who will be responsible for doing it, even though JOHS has been funded with more than $738 million dollars since it was formed 7 years ago.

If the proposed budget next year of $265 million for JOHS gets adopted, then taxpayers will have spent more than a billion dollars on the homelessness issue in Multnomah County within the space of 7 years — through JOHS alone.

A more recent development hints at some of the dysfunction Meieran has identified. When Gov. Tina Kotek in April announced disbursements to counties covered by her state of emergency for homelessness, she expressed hesitancy about handing over the funding for Multnomah County — citing vagueness in the county's plans.

"In the case of Multnomah County and the city of Portland, I'll be honest, I was disappointed that they didn't have more clarity," Kotek said at the time. "I've sat through several meetings about existing capacity, who's paying for what, where does the money come from, what's the city committed to, what's the county committed to ... they need to get their stuff together — we need to see stronger collaboration and detail."

A million little pieces

His mind somewhat boggled, Dooris circled back to Meieran's insistence that there is "no plan" for homelessness in Multnomah County, leading to the following exchange:

Pat Dooris: I'm sorry to interrupt, but I mean — I find it hard to believe ... it can't be that there's no plan. There's probably a million individual pieces of plans, that aren't all working together?

Sharon Meieran: There are a million individual pieces of plans, that's part of the problem as well that we get caught up — by we, I mean local government and then frankly in the media — once we come, you know, we have one little tiny piece of one big part of a plan, it sort of sucks all the air out of the room. It takes all the attention.

So for example, the mayor's concept of the large, you know, camp sites or whatever they're called right now ... can that be part of a cohesive, larger plan to address homelessness? Absolutely. But while we're busy arguing about that, it's like, what are we doing about the big pillars — prevention, shelter writ large — which is, you know, has to be a whole continuum, not just one little idea — permanent housing, and how are we tying all those together? There is nothing that ties them together. And by focusing on each little shiny new object that comes out with a little catchy name, we lose sight further and further of that big picture.

PD: Because at home, our attention span is somewhat limited. We've all got busy lives and so we're like, 'Oh, here's a news conference — this is going to be the solution now,' and we focus on that for a few months and then nothing changes. And then there's another new one.

SM: Exactly, and what I encourage people to do is take that step back. In thinking about homelessness what we want to see, it's three pillars. Like I said, prevention has its ecosystem of strategies. Shelter has its ecosystem of strategies; and housing. Those are the three components of a plan to address homelessness and instead of working on parts piecemeal of each of these, some cohesive body should be putting those together.

PD: Because then there could be accountability too, right?

SM: Well, that's a whole other thing as well ... we don't have the structure to create a plan. And absent a plan, we don't have accountability for any of the pieces of it. So, you know, how many shelter beds do we actually need? We don't know because we don't know how many people are living unsheltered. We don't know what they need. Could they be served best by motels? Most expensive, least sort of bang for your buck. Some people need motels, but most people do not. What's the option that can serve the most people most effectively? We don't know what people need, who they are, how many, so we can't even put that in place right now.

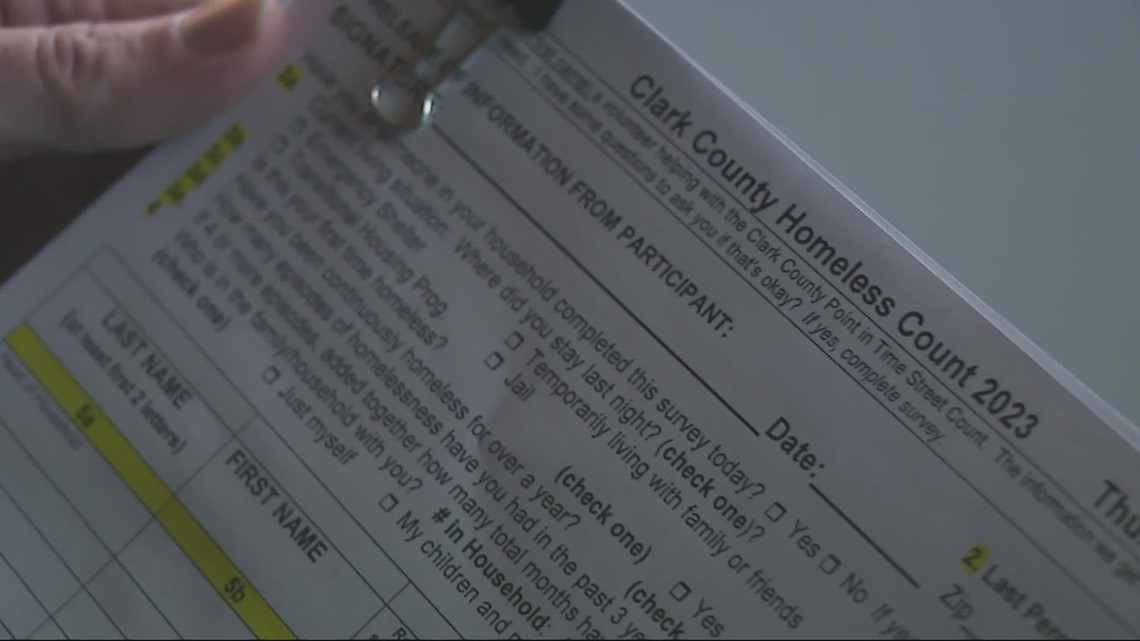

PD: OK. But to push back just for a moment, there is this point-in-time count — isn't that when we find out how many there are?

SM: No. The point-in-time count is not an actual accurate measure of really anything about who's living outside. It is, it's a snapshot. It's like a vague stab in the dark, and you can look at it over time to compare. But what it does, it goes to the places where you generally know people already are who are in the system. We reach out a little bit to those people and, you know, ask them questions. What it doesn't get to are all the people we don't know who they are.

So there are people — and I volunteer with Portland Street Medicine so I go out to places — who say they've never had any outreach worker come talk to them. They're in places that are not in the, you know, central city or places outreach goes to — no one counts those people who we desperately need to know who they are. And then even people we do count — if you're passed out if you are, you know, psychotic, if you're just feeling angry and depressed, don't want to talk to someone, or agitated — no one's gonna go up and count you. And so the people who are most in need of counting, aren't counted.

'A by-name list'

The point-in-time or PIT count is a federally-mandated survey of homelessness that each county in the U.S. has to conduct once a year. Counties have a lot of flexibility within that overall mandate, and the Portland metro area has made some strides of late in leveraging it for more useful information.

For the first time, 2023's count will fully integrate Clackamas, Washington and Multnomah counties in order to get a more comprehensive snapshot of homelessness in the Portland metro area.

But Meieran thinks it could be better. One of the things she's pushing for is a detailed name registry of who these folks are, so they can be better tracked and helped. It sounds difficult to achieve and potentially invasive, which could be a big issue for actually implementing something like that at the necessary scale. But she thinks it's sorely needed.

"Meanwhile, we have more and more people dying on the street. We have more and more people living on the street in squalor, and no one's focusing their attention on that," she said. "And we need to be saying, 'OK, go ahead, do these things with shelter, figure out how much shelter we need, what the best approach is, then invest in it' — that we need to be putting it all together in a big picture. How are we doing that?

"And that's what I feel that we should be doing every single day. There should be meetings between, you know, city, county, whomever to hammer that out — our partners — and make it happen."

In Meieran's opinion, a registry like this would include each individual's name, where they come from, what their needs are and what their barriers to housing have been. That would help, she thinks, in allocating funding where it needs to go.

"Built for Zero — you might have heard of that, but Built for Zero is a strategy to say, 'OK, now that we've identified who people are, let's build what they need to get to zero people living outside,' — functional zero, but fewer people living outside and ... where I worked with Commissioner Dan Ryan at the city, I think it's over two years ago now to get Built for Zero adopted by the Joint Office of Homelessness. There was a lot of reticence, but we were able to push it through."

According to the county's website, Portland, Gresham and Multnomah County committed to Built for Zero in late 2021. It's a national movement that includes more than 90 cities or counties "working to measurably and equitably end homelessness."

Keeping tabs on the population of chronically homeless people using a by-name list, then focusing efforts on those individuals, is a core aspect of the Built for Zero model.

But the announcement that Multnomah County has adopted this model doesn't mean that it's actually receiving the necessary follow-up, Meieran indicated.

"And then there was a lot of just sort of pausing and reticence to really implement it effectively," Meieran said. "Now there's a leaning in of saying, 'OK, we're doing Built for Zero because this is a strategy that has proved effective across the country and just makes common sense, which is what we need more of.' But as you know, now they're saying we're doing it but we're actually not. We're using our old lists. We're not reaching out to know who we don't know, like I was talking about earlier, and we need to be leaning in and doing that work. So I think there's an appetite to do that and I am heartened that we're going in that direction as more and more people truly understand it. We're not nearly there. We're not. We do not have a by-name list and we need one."

In the meantime, Meieran is encouraging residents of Multnomah County to show up at board meetings, get familiar with the conversations going on around these issues and testify if so compelled.

Regular meetings of the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners are held on Thursdays at 9:30 a.m. People can attend in-person at the Multnomah Building on Southeast Hawthorne, Boardroom 100. The first part of every meeting is reserved for public testimony.

People can also watch the meetings and even testify virtually from home. You can sign up to testify online here.