PORTLAND, Ore. — As Multnomah County's leadership faces immense pressure over its response to homelessness, behavioral health and addiction issues — and particularly the millions of dollars that the county spends yearly on each — the county auditor just wrapped a review of the county's budget process. The results could be illuminating for residents frustrated with how things are going.

Multnomah County Auditor Jennifer McGuirk started her second four-year term back in January. An elected position, the auditor's role is far from simple; it's a vital watchdog charged with ensuring that county government is efficient, transparent and accountable to the hundreds of thousands of people who live in the county.

The county's budget, a whopping $2.8 billion this past fiscal year, is a huge part of that oversight. It includes Multnomah County's general fund, nearly $750 million primarily made up of residents' property and business taxes, which commissioners determine how to dole out to different departments and programs year after year.

"We looked at how understandable is the budget process and how transparent is it for community members, and we found that, in many ways, the county's budget process really does meet best practices," McGuirk said. "But we would like to see better transparency in how the county reports on its budget, and we would like to see more time for really meaningful community engagement in the budget process, as our recommendations focused on those two areas."

Apples and oranges

McGuirk said that one of the reasons she wanted to get this audit done was because she's heard questions for years from community members who look at the county budget site request the documents detailing how some of that money is spent, then notice that the numbers do not always line up. There's a reason for that, and it doesn't have anything to do with mismanagement or criminal malfeasance — it's a result of the systems the county uses.

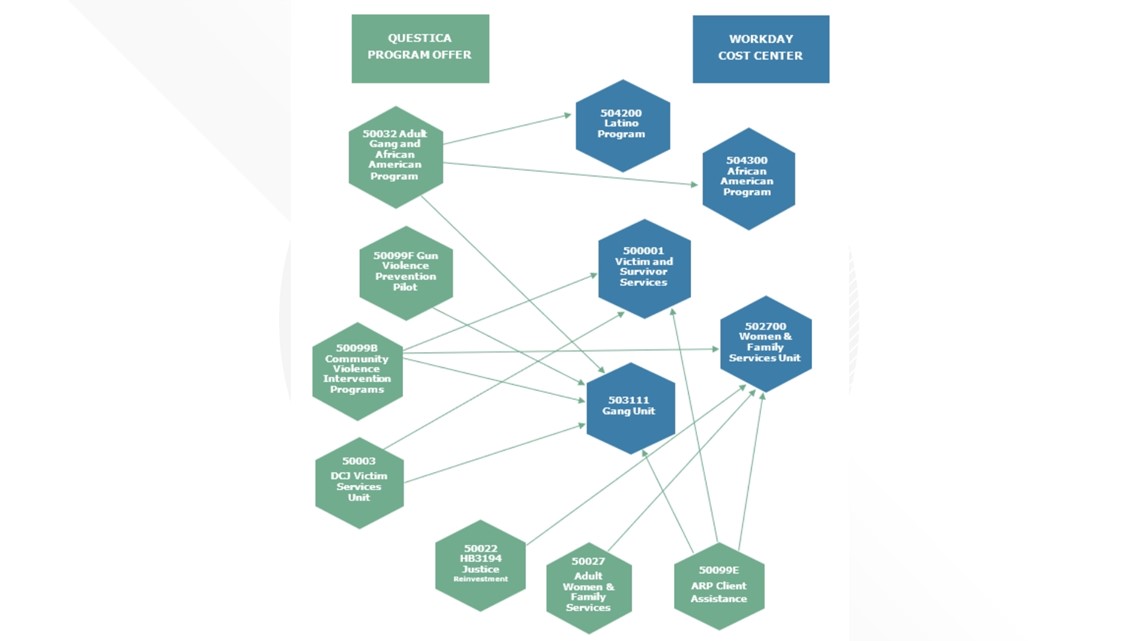

"When the county budgets, each county office or department submits what they call 'program offers,' which is a budget for programs in their portfolio, and that's how the board adopts the budget at that really low program offer level," McGuirk explained. "But the county's financial system doesn't work in program offers; it works in cost centers, and program offers and cost centers don't always line up."

In a recent year, McGuirk said, there were about 600 program offers, and over 130 of them didn't line up perfectly with the cost centers.

It's perhaps easier to visualize than it is to describe the relationship between the two. The graphic above is an example of the breakdown for Multnomah County's Department of Community Justice. While there are seven program offers (in green), there are only five cost centers (blue).

This distinction became the crux of McGuirk's audit. The county commissioners make their budget approvals based on program offers, but the reports that cover how the money is spent come from cost centers. That becomes a hindrance for the public's understanding of a clear cause and effect.

In fact, the audit concludes that the way Multnomah County does things now "makes it difficult, if not impossible, to meet best practices for financial monitoring."

Those best practices are outlined by a group called the Government Financial Officers Association, which stipulates that "a government should be able to show if it has actually purchased goods and has actually provided services."

"It's unfortunately more complicated than I think it should be," McGuirk said. "Which is kind of why we're saying, 'Hey, let's report it the same way we're budgeting,' so it's not that they aren't spending that money; it's that cost centers look at revenues and expenditures differently than a program offer does."

McGuirk gave a hypothetical example, similar to the real one above, that seven program offers might feed into five different cost centers.

"I think the issue is the budget system speaks in one language and the finance system speaks in another. And so it's very hard to translate between the two of them if you don't have an office that has one program offer and one cost center," she said. "It's not that those metrics aren't being met, but reporting it in a way that is easy to understand is difficult."

After untangling this web, it bears repeating that McGuirk's office did not find any evidence of mismanaged money or fraud. Instead, they found the challenges county staff have in trying to reconcile taxpayer spending in a way that's transparent for the public.

"No one wants that (lack of transparency)," McGuirk said. "It needs to be easy for us to understand how our taxpayer dollars are being spent."

One step the county can take, her office determined, is to periodically report on spending through the program offer lens to the board so that the public can actually compare the board's budget to the county's spending — apples to apples.

Feedback falls behind

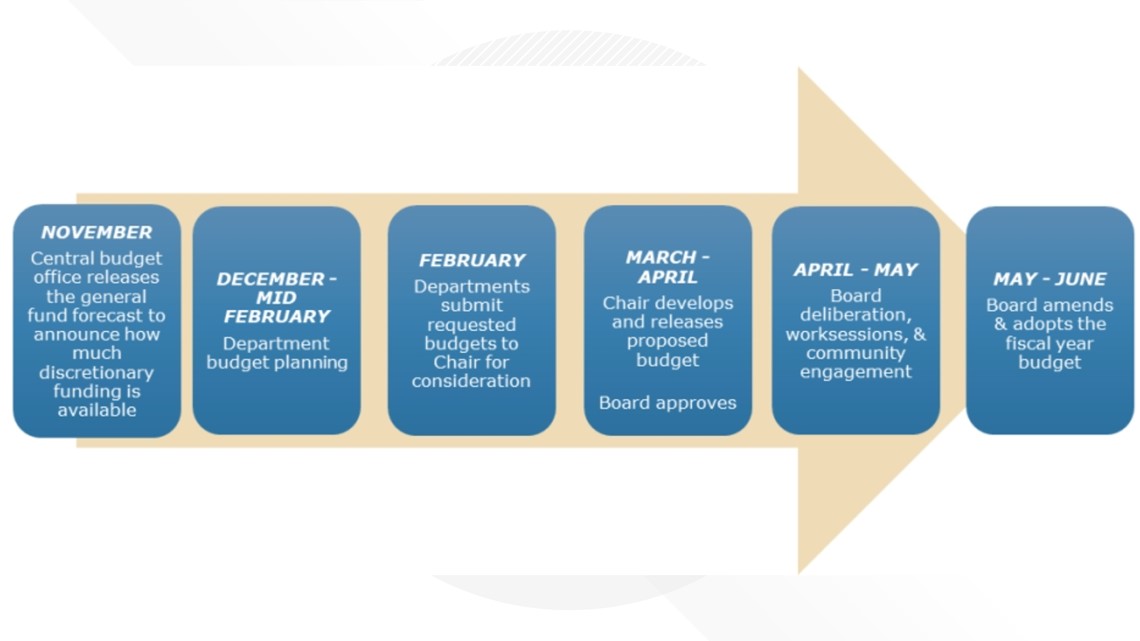

The audit also looked at the various "citizen budget advisory committees" that are supposed to give input on department budgets. McGuirk's office found that the timeline of the budget process makes it hard for those volunteer committees to actually have an impact.

Right now, the budget process starts in November with the general fund forecast. Then departments begin prepping their budget requests, submitting them to the county chair in February. Once that happens, these advisory committees are supposed to look over the requests and submit a letter to the chair with feedback — then, the chair is supposed to develop and release a proposed budget.

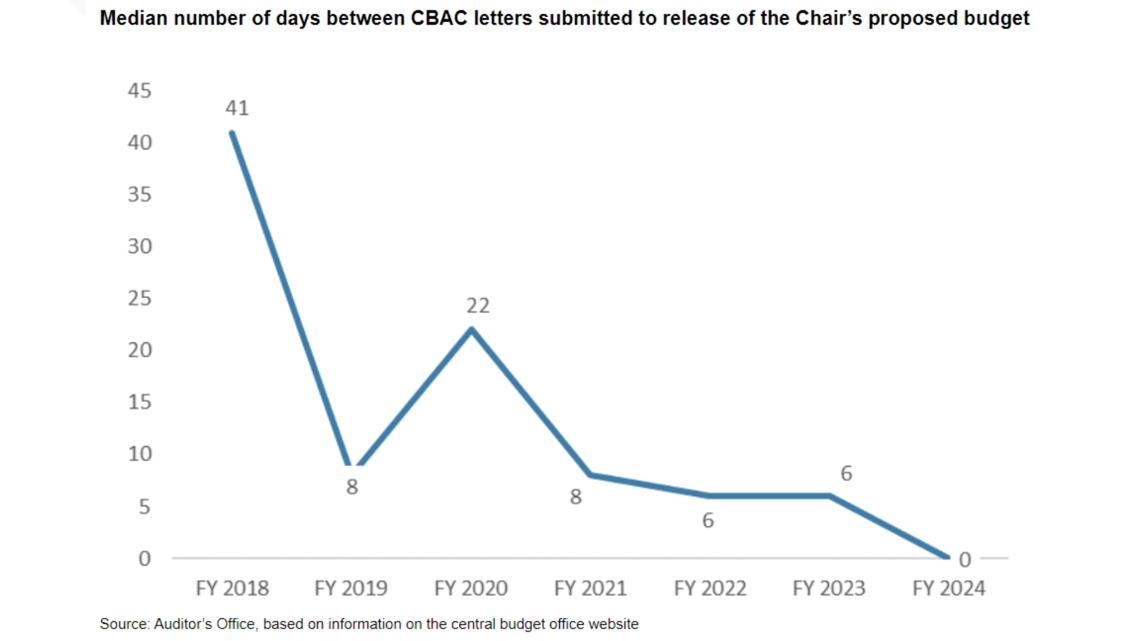

But the audit found that those committees "rarely get those letters to the Chair in time to have an impact on the budget."

"With this in mind," auditors went on to say, "it is not surprising that CBAC members surveyed by the Office of Community Involvement said they did not believe their input had an impact on the budget."

It isn't first time that this issue has come to light. Last month, The Story spoke to the leader of a budget committee meant to oversee the budget request from the Joint Office of Homeless Services. He did not have positive things to say about the county's commitment to listening to their feedback.

"The county doesn't want to have oversight on the way it's spending money, so that it can continue to spend money in a way that doesn't actually address the problems that Portlanders have," said Daniel DeMelo, advisory committee chair and now candidate for Portland City Council.

Auditors made a graph to show the median number of days between those committee letters being sent to the county chair and the chair releasing a proposed budget. In the last three fiscal years, those letters were sent less than a week before the budget's release. This past spring, there was absolutely no daylight between the two.

The audit suggests that Multnomah County could switch to a two-year budget process, much like the Oregon Legislature's biennial budget, which would allow more time for educating the public about budget options and would give these committees time to actually influence how tax dollars are spent.

The chair's response

Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson said she agrees that the confusion over that distinction between program offers and cost centers needs addressing, and she said that the county was already working on a process to fix that. They also plan to create a budget monitoring dashboard to show the actual operating expenses of departments.

As for switching to a two-year budget cycle, Vega Pederson said the county's chief operating, budget and financial officers will meet to discuss details on how to study the impacts of switching to a biennial budget and will report to the board of commissioners with what they find out.