PORTLAND, Ore. — Editor's note: This is one part of an ongoing series of stories exploring the impact of Measure 110 in Oregon from a variety of perspectives.

After overcoming addiction and serving a sentence in federal prison for a drug-related crime, Morgan Godvin knows the criminal justice system isn't the best way to help drug users get into recovery — because she's lived through it.

It's why she's a supporter of Measure 110, the ballot initiative that decriminalized small amounts of drugs in Oregon to prioritize treatment for individuals over jail time.

"I found recovery despite my incarceration, not because of it," Godvin said.

She now serves on the Measure 110 Oversight Oversight and Accountability Council, the volunteer board made up of citizens that is tasked with determining how grant funds are distributed. She's also a commissioner on the state Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission.

Godvin grew up in Gresham in a military family. She said her journey with addiction began after she joined the Air Force and was injured in basic training.

"I ended up back home and I was super depressed about that," she said. "It was the boom of the OxyContin era ... and when that got too expensive, like most of my friends from East County we switched over to heroin," she explained.

After an arrest for felony possession, Godvin ended up in Multnomah County drug court.

"Because of the life I'd lived, I really respected law enforcement, authority — and I believe this is a fair and just nation, so I leaned into the system. Because why else do we arrest people for drugs unless it's there to help them?"

Godvin said she volunteered to go to jail because she thought it would help her. She expected to be given the Suboxone medication that she'd been prescribed to help her treat opioid addiction.

"The medical staff that night laughed in my face and told me they do not prescribe Suboxone, they do not prescribe medications for opioid use disorder, even though I'd been prescribed it by my doctor. They made me kick cold turkey in an open dorm with fluorescent lights that never turned off, vomiting in a trash can in front of 77 other people," Godvin said. "Why? For what? I had asked for help, I had leaned in to the criminal justice system thinking it was there to help me, and instead it betrayed me."

Godvin said someone she met in jail ended up becoming her co-defendant in a federal drug-induced homicide case after acting as a middleman supplying drugs to a friend, who died of an overdose. She lost her job, descended into addiction and eventually ended up in federal prison.

She cited the resources available to her as a middle class white person and having a strong social network as the reasons she got sober and found success in her recovery. She said a friend helped her enroll in classes at Portland State while she was still in prison so she could start right after she was released.

"What I needed was hope for my future and a purpose for my life, and I created those things for myself and that is the foundation for my recovery."

She acknowledges not everyone is so lucky. Godvin said she has lost six friends to overdoses.

"Every single one of my friends that died of a heroin or fentanyl overdose was incarcerated repeatedly first. What if that money would've been spent on prevention?" Godvin said. "The government spent $1.2 million incarcerating my co-defendants and I. Where was that money while my friend Justin lived? Because all they did for him while he lived was call him a criminal, give him a dozen jail sentences and a prison sentence. The moment he died, his life became worthy of government intervention and resources."

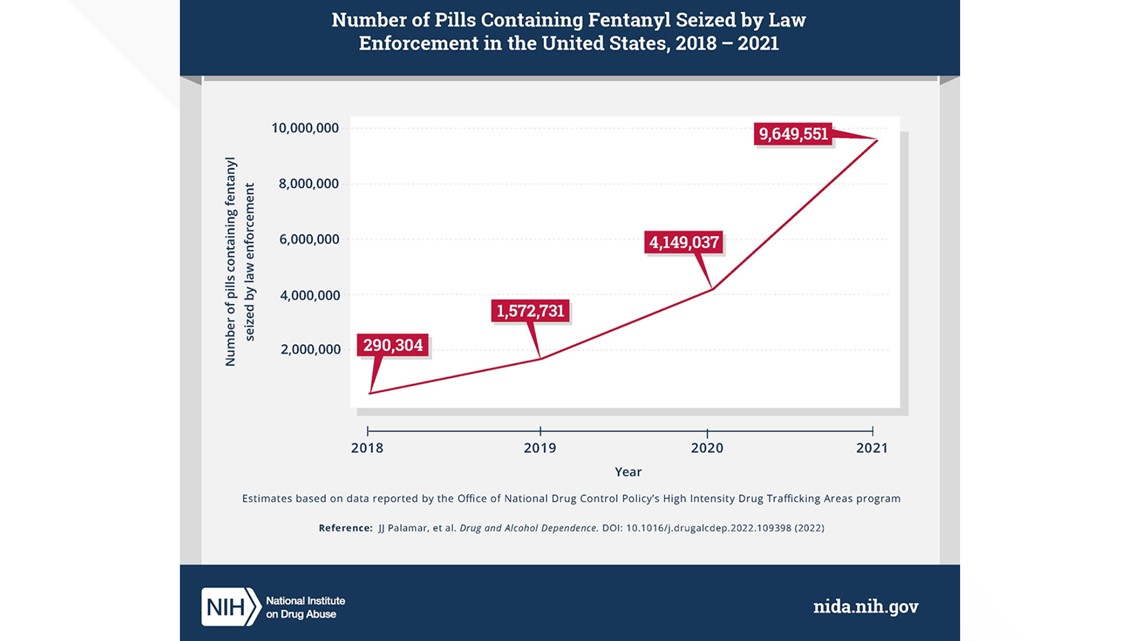

Godvin pushed back on the narrative from law enforcement that Measure 110 brought more drugs to Oregon, noting the entire country has seen a massive surge of fentanyl use.

"Because of the committees I sit on, I see the same data as all the other law enforcement officers. So they know very well that these are national trends, from the firearms to the homicide, which has absolutely nothing to do with Measure 110. That is a national scourge that we are experiencing," she said. "Oregon is not exempt from this national trend, but it is not unique."

Godvin pointed out that in Oregon, dealing drugs is still a crime, and Measure 110 only legalized possession of one day's worth of a user amount of drugs — someone with more than that could still be charged with a misdemeanor.

"The notion that decriminalization of incredibly small user amounts led to more higher level crime is just not backed up by the data. And we see this nationwide: a state's incarceration rate has no impact on its substance use rate," Godvin said. "The cartel does not care that we decriminalized drugs."

A major criticism of Measure 110 is the lack of implementation of the treatment side of the initiative, which provides grant money to organizations to form addiction treatment centers. So far, very little of that money has actually been doled out.

The slow bureaucratic process has frustrated Godvin, too.

"There was some changing goal posts, constant changing directives, bureaucracy, Department of Justice intervention. A lack of urgency on behalf on behalf of the Oregon Health Authority is what I perceive — very frustrating, because my friends are out here dying."

She said by the end of this month, the oversight committee will be done reviewing applications for grants, and she expects $270 million to be distributed across the state within a few months.

"When you give people better options, they make better choices," Godvin said. "I am a member of this community and I also value public safety. The way to reach true public safety, public wellness, is to give people better options so that they make better choices."

Godvin's advocacy for drug users and those in recovery goes beyond serving on state and local commissions — she also founded a group called Beats Overdose that brings harm reduction services to music festivals and concerts.

"You cannot punish the hurt out of someone, and hurt is so often the reason that we use drugs," Godvin said.