PORTLAND, Ore. — A new interactive model predicts that the heat waves we've seen in the Pacific Northwest over the past several years are not going away — in fact, they're going to get progressively worse year after year.

To help show us what's coming, a nonprofit created a tool called "Risk Factor." It allows people to get an educated guess on how heat, floods and fires will likely affect their homes within the next 30 years. It even includes how much we may have to spend on heating and cooling bills within that 30-year window.

The tool works like this: Input your address, and Risk Factor will tell you if your location is most likely to face flood, fire or heat risks in the next 30 years.

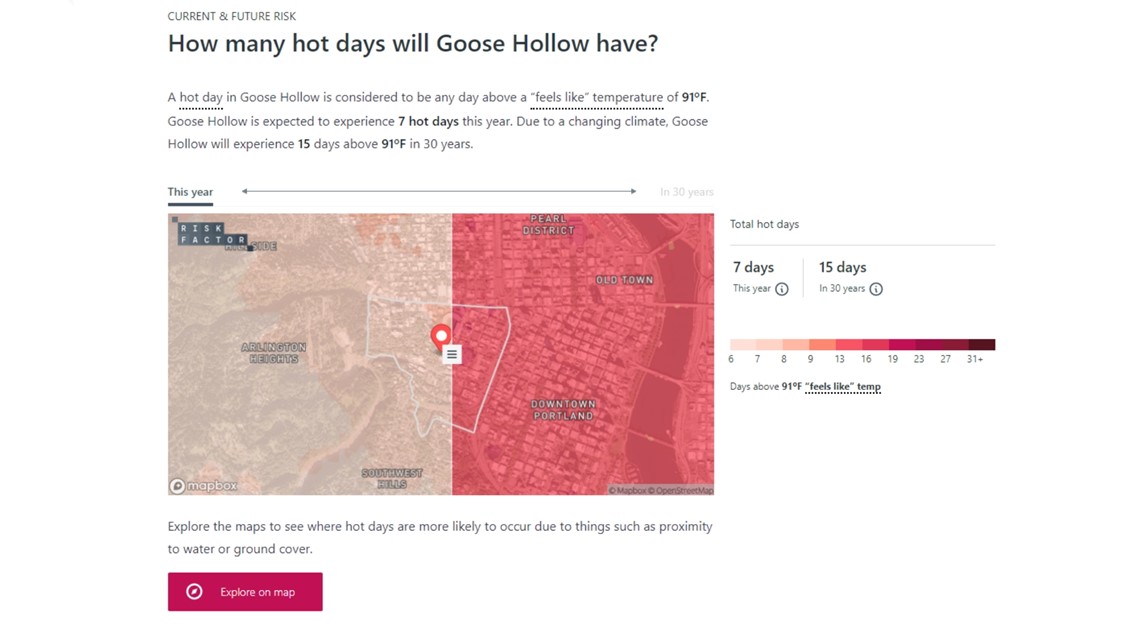

For example, KGW's studio is just on the edge of the Goose Hollow neighborhood in Portland. Risk Factor predicts that we'll likely see an impact from heat, doubling the number of days above 91 degrees within the next 30 years.

Heading east to Pendleton, all three factors — heat, flood and fire — are expected to make an impact. The address we used has a very small chance of wildfire impacting it this year, just 0.21%, but that percentage is expected to grow each year. Eventually that home will have an 8.5% chance of seeing a wildfire at least once over the life of a 30-year mortgage.

If we go even further east to the town of Wallowa, flooding is expected to be the biggest risk factor. We chose a random property off Highway 82, right next to the river. That home could see flood waters as deep as 8 feet during a major flood. In the next 30 years, the tool predicts that amount will rise by 6 more inches — spreading to more homes and neighborhoods. Even though the change sounds small, just one inch of flooding in your home can cause major damage to the structure, and of course, your belongings.

Jeremy Porter, chief researcher at First Street Foundation, helped create the risk map. We wanted to know why this specific tool matters to Oregonians. Porter said that they wanted to create a more impactful and easy-to-digest map for understanding climate change within the next three decades, rather than trying to look 100 years into the future. Regardless, he said, the heat is coming.

"On the Western half of the country, the temperatures are a little bit lower, but we do see what are called 'local hot day,'" Porter said. "Heat waves happen [at a] higher probability ... the Weather Service actually calls those local heat waves, 'lethal extreme heat events' because of the fact that people aren't acclimated to the temperatures. And what we saw in Portland last year, what we've seen in Seattle this year and last year are really the same — that sort of 'local hot day' heat wave effect. And in the Western part of the country, we actually see a high, the highest probability, of those heat waves relative to the rest of the country."

There's no denying how dangerous these stretches of heat can be. Nearly 100 people died statewide during the 2021 heat dome event. Upwards of a dozen people died during the milder heat wave this summer.

"The National Weather Service actually calls heat and extreme heat exposure the deadliest, or one of the most lethal climate perils. And it is because of that prolonged exposure to extreme heat events ... that have enormous health implications," Porter continued. "It only takes us getting to 80-degree health index where — or heat index — where people start to respond with dehydration and fatigue, heat cramps. If you go into the 90-degree and 100-degree thresholds, and you're starting to get in the heat stroke level. So people that are outside all day long, they're generally exposed to even higher temperatures than what we see on the heat index, because they're working oftentimes on concrete and in places that tend to be hotter, or on roofs or doing construction, and those types of things where they bear the brunt of the heat exposure."

Beyond the direct health impacts, Northwest infrastructure at the local, state and even federal level was built for the weather we've all been "used to." Porter explained that the increase in power usage for things like air conditioning units could also affect us on a larger scale.

"Some people may have air conditioners. The further north you go, the less and less likely you are to have people that actually even have air conditioners," Porter said. "So there's this chance of a prolonged exposure to extreme heat events without actually having protections from things — like in the south, air conditioning is ubiquitous, everywhere you go air there's air conditioning on and it's there to protect people in those areas from that extreme heat exposure. In places where that doesn't exist, there's both a lack of personal protection from having access to air conditioning, but there's also problems with the infrastructure grids, which are built to supply energy for a certain level of cooling degree days, which is the industry standard for how hard and how often air conditioners have to run during extreme heat events. If it gets warmer, the grid itself may not be able to keep up with the power load and you may see brownouts, you may even see blackouts in the worst-case scenarios. So there is, there is some concern over those areas where they're just not acclimated to that type of extreme heat event."