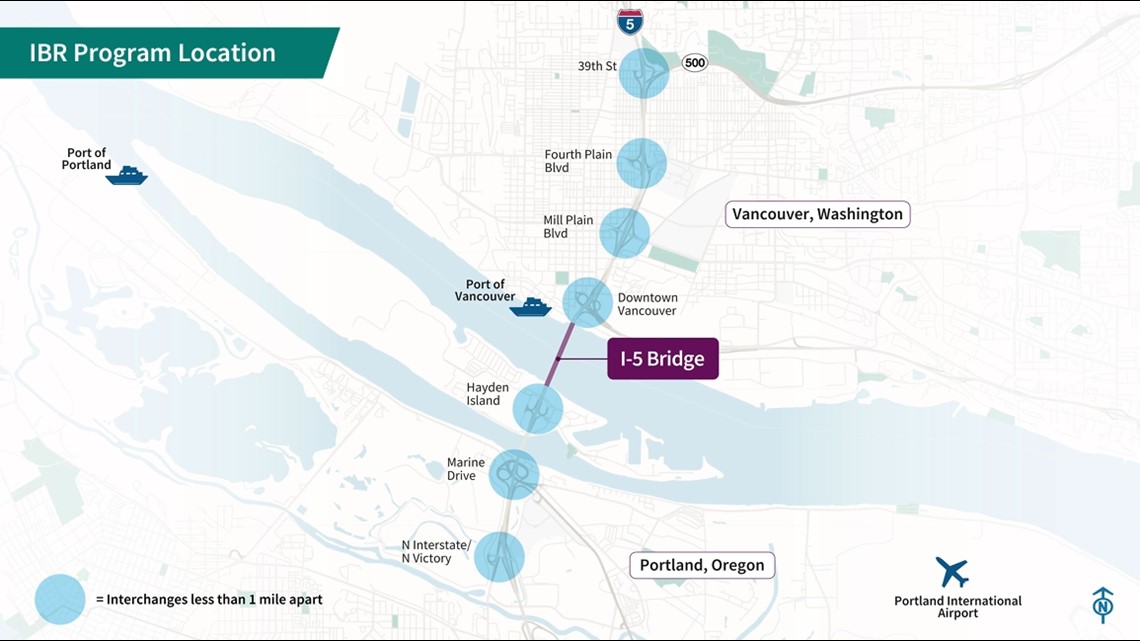

PORTLAND, Ore. — The Interstate Bridge Replacement Project aims to transform not just the I-5 river crossing itself, but several miles of the freeway to the north and south, rebuilding or adjusting a total of seven interchanges in Vancouver and north Portland.

Freeway interchanges aren't most glamorous topic, but it's important to keep an eye on them for a couple of reasons. First of all, according to the project team, more than 80% of trips through the corridor use one of these seven interchanges. So if you drive anywhere along this stretch of I-5 on a regular basis, your route could likely be impacted.

And secondly, taken together these upgrades are expected to cost somewhere between $2 billion and $3 billion, with the overall project cost expected to be about $6 billion. So these aren't small details — they represent as much as half of the project's price tag.

Simple and less simple

The IBR project team recently published a pair of YouTube videos — one for Oregon and one for Washington — that go through the plans for the rebuilt interchanges in detail, using animated arrows to illustrate every possible pathway that drivers can take to get on and off the freeway, and how they’re going to be different after the project gets built.

Many traffic movements will stay fairly similar, and some may even get less complicated. At Marine Drive in North Portland, for example, drivers heading onto I-5 northbound won't have to duck under the freeway and go through a looped ramp anymore — they can just make a left or right turn at an intersection.

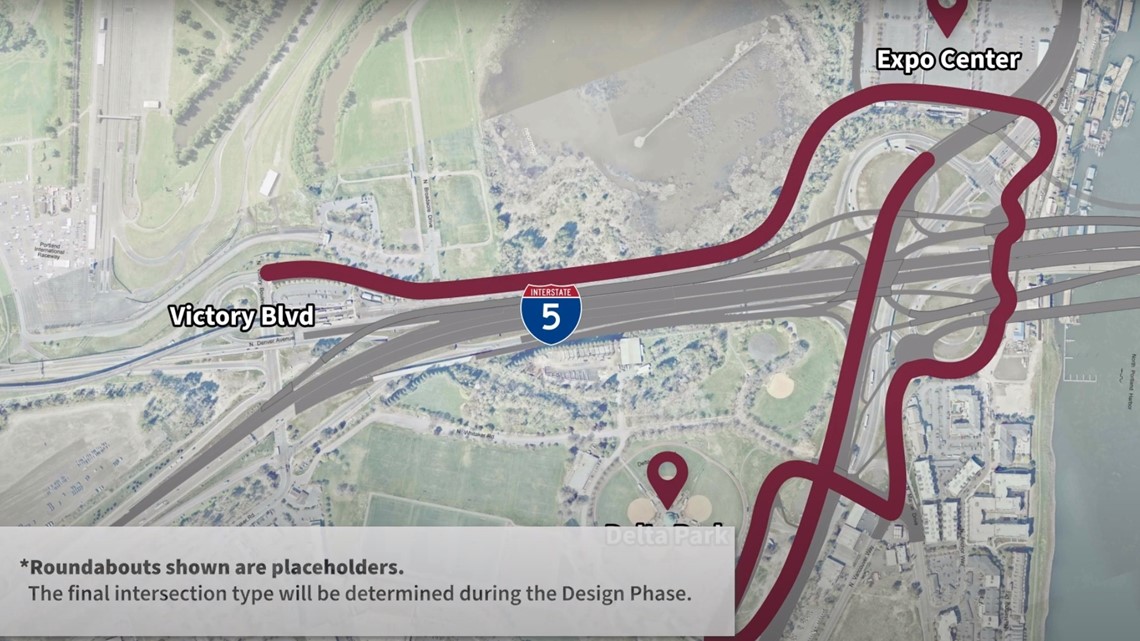

But there are some changes where the viewer might be forgiven for wondering, "Wait ... why are we doing this?" For example, if a driver is trying to get from Marine Drive to Victory Boulevard, it's currently an easy hop onto I-5 and then back off at the next exit. After the Interstate Bridge upgrade, that route becomes much more complicated.

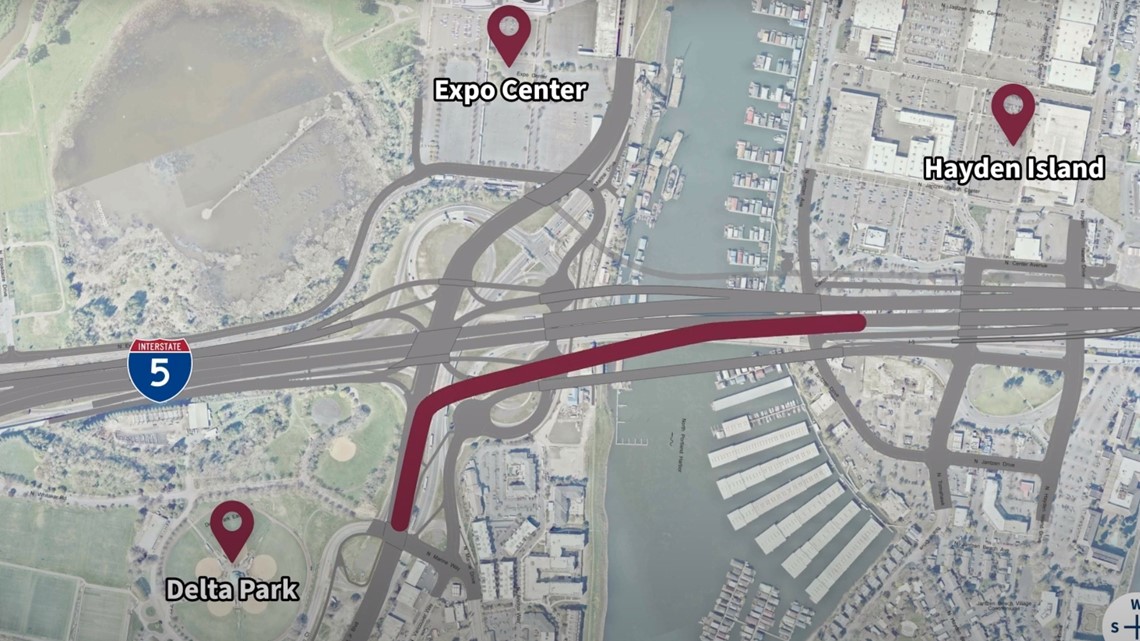

The same goes for getting onto I-5 southbound from Hayden Island, which would involve crossing a separate bridge to the Oregon mainland and then passing through multiple intersections beneath the freeway to get to an onramp, instead of just hopping directly onto the freeway from the island the way drivers can do today.

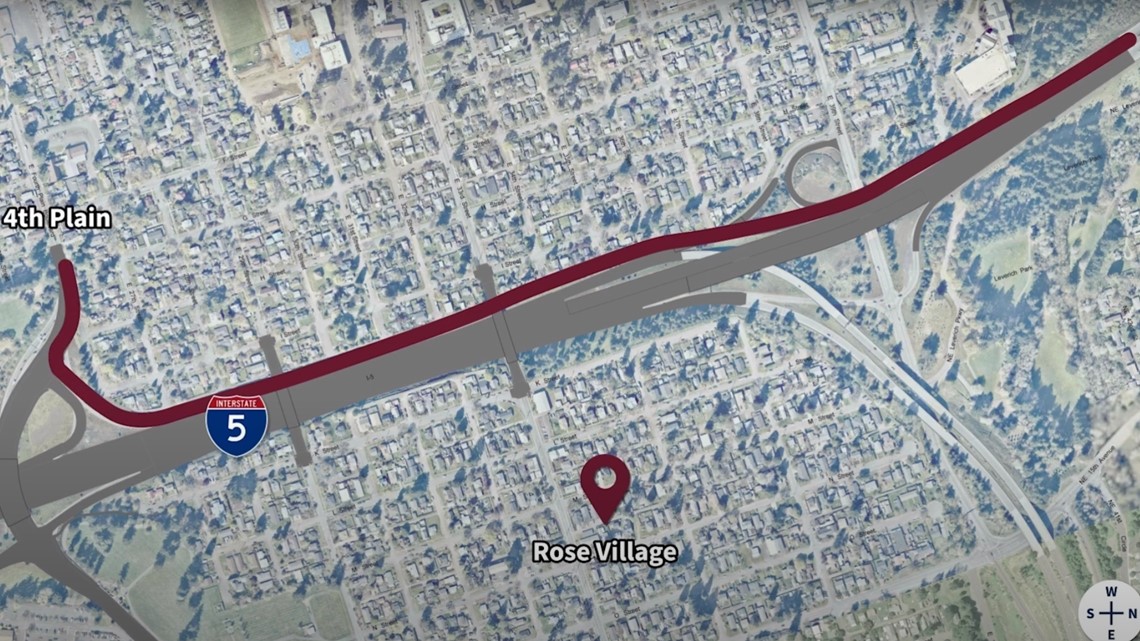

Some other movements will still be pretty straightforward, but stretched out. There will still be a direct exit from I-5 southbound to Fourth Plain Boulevard in Vancouver, but the exit ramp will start much farther back, to the north of the interchange with State Route 500.

Interchanges too close

IBR design manager Shilpa Mallem and delivery manager Casey Liles spoke to KGW to walk through the reasoning behind some of the planned changes.

One detail they stressed: none of the plans shown in the videos are locked in. They're early concepts being studied as part of the federal environmental review process, but they're not yet full designs and they can still be adjusted, including in response to public feedback. They said the project team wants to hear what Portland and Vancouver residents think about the plans.

As far as the changes currently on the drawing board, Mallem and Liles said a lot of the adjustments are aimed at addressing a core problem with the stretch if I-5 surrounding the Interstate Bridge: there are too many interchanges spaced too close together, in some cases overlapping.

"That creates the friction, either causing slowing or the safety concerns where people take chances and make decisions quickly," Liles said. "Maybe not look over their shoulder when changing lanes."

The result is that the corridor's crash rate is about three times the state average, Mallem added, and backups on the freeway tend to radiate out into the surrounding city streets on both sides of the river.

But if there are too many interchanges, why not just get rid of a couple?

"It's not as simple as taking away these movements," Mallem explained, "because people are dependent on those movements and they are providing a function. Today it's an urban area. Each one has their own unique function."

Without being able to take any interchanges out, the project is left with trying to make all seven play nicer with each other, and that's the driving force behinds some of the bigger changes.

Uncrossing the streams

The much-longer exit ramp from I-5 to Fourth Plain Boulevard is an example of trying to untangle the interchanges — in this case, separating the stream of cars heading off I-5 onto Fourth Plain from the stream of cars entering I-5 from SR 500 in the same space.

The new "braided" ramp will carry the exiting traffic over the entering traffic, reducing the friction caused by the two interchanges being so close together. I-5 northbound already has a braided ramp that jumps exiting Fourth Plain traffic over Mill Plain Boulevard. The IBR plan would add a couple more ramps like that throughout the corridor.

The tradeoff for the braided ramp is that drivers on 39th Street won't be able to hop on I-5 at the SR 500 interchange to reach Fourth Plain — they'll have to get there on city streets instead. But that's more of a feature than a bug — in some cases the plan is to further reduce the number of merges happening on I-5 by redirecting short trips away from the freeway altogether.

The route from Marine Drive to Victory Boulevard in Portland is another example — the new path will be more complicated, but it will also avoid I-5 altogether. Getting local trips off the freeway is also the reason for one of the biggest peripheral pieces of the project: a local bridge from Hayden island to the Oregon mainland, which will allow access to the island without having to use I-5.

"What we heard from the community is there's no other way of getting off the island (or) on the island in the state," Mallem said. "So that contributes to the local arterial bridge, where you have a different way of getting on and off."

Downtown Vancouver overhaul

The most complex rebuild by far will be the interchange immediately north of the main bridge, where State Route 14 connects with I-5 and both freeways connect with downtown Vancouver.

The design of the new bridge could still go one of two ways: It could be a drawbridge like the current one, or it could be a fixed span that doesn't move. It's ultimately up to the U.S. Coast Guard, but the IBR team is pushing for a fixed span, which would be much higher up — and that's why the videos depict the new SR-14 interchange on three different levels.

On the ground layer is the Vancouver street grid, which would be rebuilt through the area once the freeway is lifted out of the way. The middle layer has various ramps carrying traffic between the two freeways and downtown, and the top layer has the main ramp carrying I-5 and the included light rail line up to the bridge.

Several ramps will connect to different places on Vancouver’s street grid than they do now. Traffic flow is a factor there, according to Liles, but there's also a practical consideration: the new interchange has to coexist with the old one while it's being built.

"We have to be able to build this while keeping traffic moving, moving on the freeway in three lanes in each direction through our peak hours... in the entire duration of the program," he said. "So not only do we have to develop our design so that it's great and reconnects, we have to consider how that's able to be constructed while still having traffic move through the program."

One striking feature of the SR-14 interchange diagram is a large green paperclip-shaped line on the left side of the middle level diagram, which represents a spiral ramp to carry bike and pedestrian traffic up to the new bridge.

The ramp's design is due to a couple constraints, according to Mallem and Liles: the project team doesn't want it to be steeper than a 4.5% grade, but they also don't want it to stray very far from the bridge, in order to make sure Vancouver's rapidly-developing waterfront district becomes the hub for non-vehicular traffic to access the crossing — that's also why the IBR plan calls for a light rail station above the waterfront nearby.

"This is where trade-offs come back into play," Liles said. "In order to get bicycle and pedestrian active transportation down to the waterfront, we need to make something like this, either a ramp that goes down to the waterfront or something like elevators, escalators, stairs. Those trade-offs, all decisions all have to be made in order to get to active transportation on the waterfront."