PORTLAND, Oregon — Regular riders of Portland's MAX light rail system are all too familiar with the problem: the trains zip in quickly toward the city center along Interstate 84 and the Robertson Tunnel, but they slow to a crawl as soon as they hit downtown, often making it so the final couple miles of a trip take almost as long as the whole rest of the journey.

Portlanders who have visited New York, London or even Seattle may have noticed that those cities don't have the same problem, thanks to a key piece of infrastructure that Portland lacks: downtown train tunnels. The observation raises an obvious question: can Portland still catch up?

The answer is yes — it isn't going to happen anytime soon, but the idea of a downtown Portland MAX tunnel has been around for a long time, and TriMet and Metro have both taken some early steps to study what it might look like.

Speed and the Steel Bridge

Running on dense city streets and surrounded by mixed traffic, MAX trains are limited to just 15 miles per hour when they cross downtown Portland — and factoring in station stops and waiting for cross traffic, the average speed is even slower.

TriMet knows its a problem, and in recent years the agency has tried to speed things up by closing a few downtown stations that were spaced too close together and upgrading the tracks on the Steel Bridge so trains can cross a little faster.

Those improvements help, but the gains are marginal; it currently still takes an average of 22 minutes for a train to travel between the Goose Hollow and Lloyd Center stations and west and east ends of downtown. The next station on the chopping block is Skidmore Fountain, but TriMet estimates that taking it out will only save about 40 seconds.

Truly speeding things up would require a whole new route that takes the trains off the streets altogether, which is where the tunnel concept comes in. TriMet and Metro have both looked into the idea, first with a TriMet study in 2017 and then with a Metro study two years later.

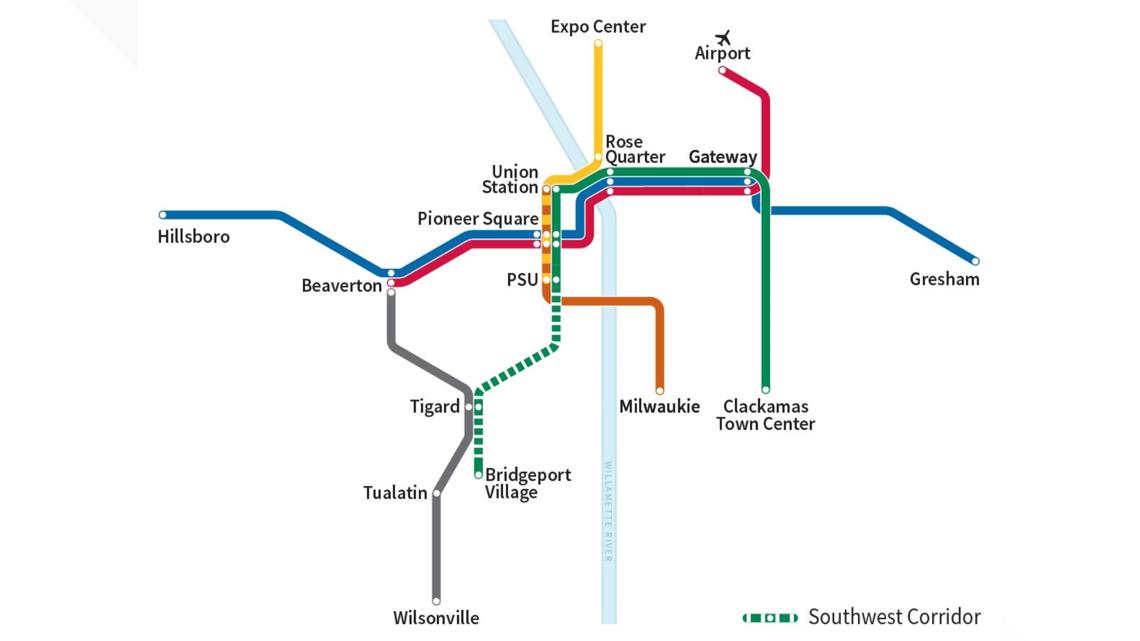

Train speed was definitely a factor in the studies, but the biggest driver was actually a separate problem: the Steel Bridge, where all of the MAX lines converge to cross the river on a single set of tracks.

The shared crossing makes the Steel Bridge a bottleneck, and any delays on the bridge can quickly ripple through the entire system — just a couple weeks ago, a derailed fright train on the lower deck caused the entire Steel Bridge to be closed for several hours, blocking every MAX line. And even when things are running smoothly, there's an upper limit to how many MAX trains can physically cross the century-old bridge per hour.

"We're not at the upper limit currently, but future changes and improvements to the system could put us towards the upper limit," explained Metro Urban Policy and Development Manager Eryn Kehe, who worked on the agency's 2019 study.

The TriMet and Metro studies were each focused on evaluating options to solve the Steel Bridge bottleneck, with the TriMet study screening down a wide range of options and the Metro study narrowing it down further to a final recommendation.

Some of the other ideas in the TriMet study included adding a second set of tracks on the Steel Bridge, building a second bridge to take over MAX traffic or split the load, or even rerouting one or more MAX lines to one of Portland's other bridges like the Broadway Bridge. But each one had drawbacks; a second set of tracks might have unbalanced the Steel Bridge deck, TriMet found, and any new bridge would require extremely long onramps that would be difficult to fit into surrounding blocks.

Metro's tunnel plan

The Metro study concluded that a tunnel would be the best option to solve the Steel Bridge bottleneck, in part because it avoids the problems with the above-ground crossing options, and in part because it would solve the downtown speed problem at the same time. It's also the only option that would allow for the possibility of running longer trains, because the underground station platforms wouldn't be limited by the length of Portland's city blocks.

The tunnel as envisioned in the study would be exclusively for the Blue Line, turning it into a sort of express route for riders passing through downtown. The other lines would remain on their current surface routes to keep serving existing stations, but they would still benefit from the removal of the Blue Line from the Steel Bridge.

"By reducing the number of trains using the bridge, you eliminate some of those reliability issues that you had before," Kehe explained. "And you have a great time savings for folks riding the tunnel. We found an 11-minute savings from the Lloyd Center to Goose Hollow on the Blue Line."

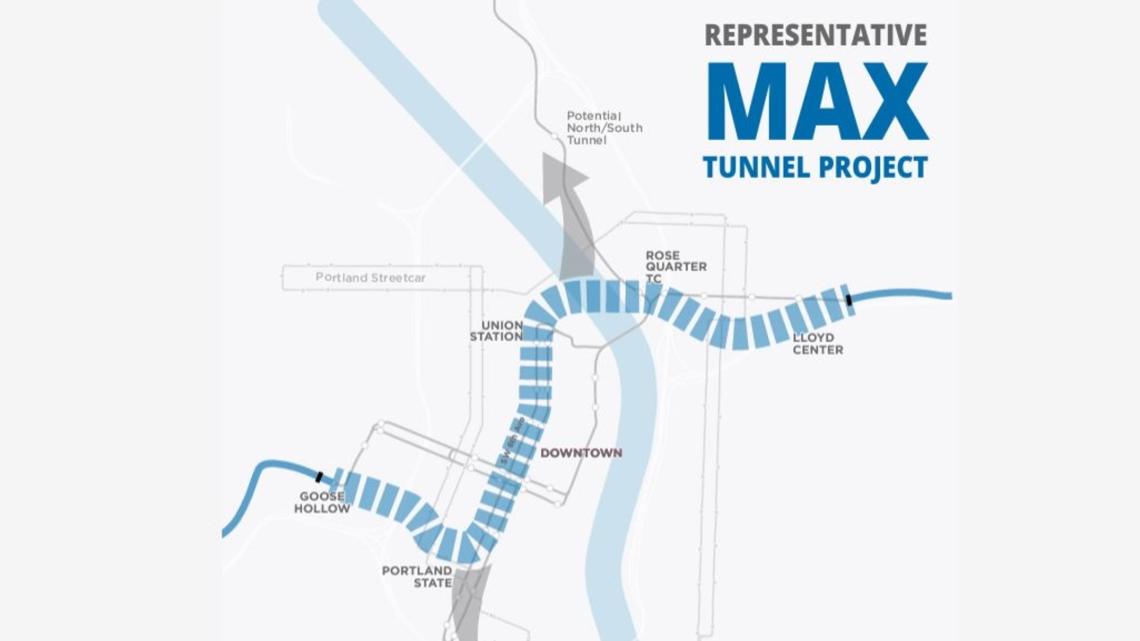

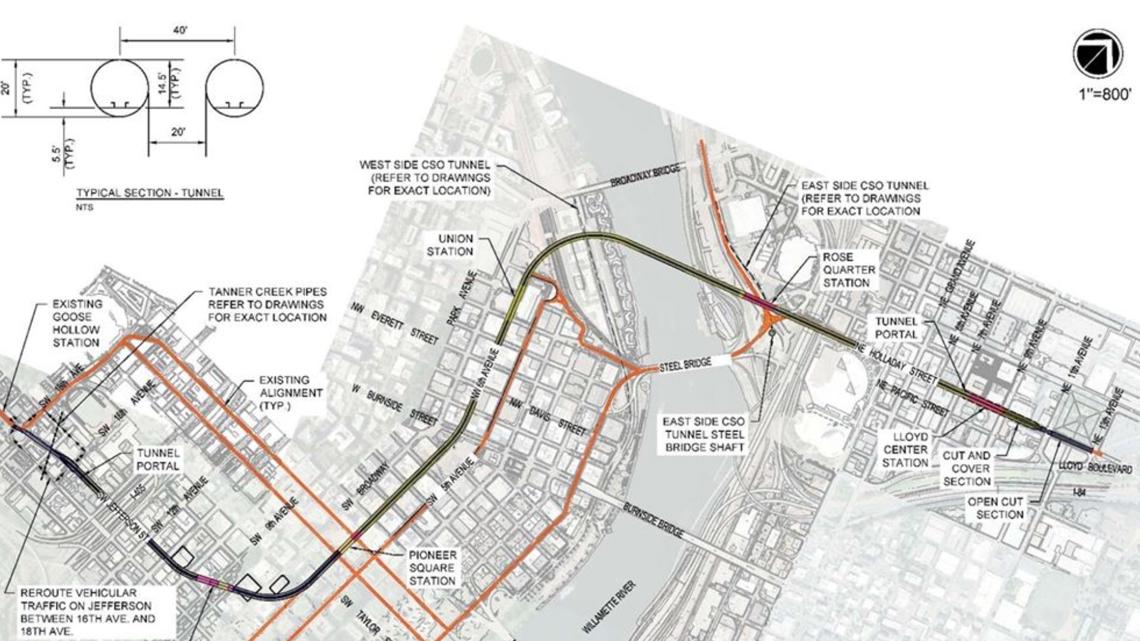

The exact tunnel route wouldn't be determined until the project got further into development, but the Metro and TriMet studies both mapped out similar example paths. The new tracks would split off by the Goose Hollow station and continue down Jefferson Street, diving underground to pass below Interstate 405.

The tunnel would continue east toward downtown, then turn and head north near 6th Avenue, roughly paralleling the Green and Yellow Line tracks above ground. Then it would turn east again, passing under the river and lining up under Holladay Street, popping back out and rejoining the current tracks at the Lloyd Center station.

The total tunnel length would be about three and a half miles. The number and locations of the underground stations would be determined further into development, but there would likely be fewer stations than on the surface line.

"Four underground stations is what we studied, what we looked at, but a lot more analysis is needed," Kehe said. "That's why we were ... we went to voters in 2020 with the Get Moving transportation measure, seeking funding to take this to the next step of environmental review and further design."

The 2020 setback

Metro's Get Moving 2020 ballot measure would have imposed a payroll tax to fund a host of regional transportation projects, including a new MAX line to Tigard and further development of the downtown MAX tunnel plan.

The Southwest MAX project was further along in development, with environmental review already completed and an exact route mapped out, so the ballot measure was intended to raise funding to begin construction. The downtown tunnel would only have received enough funding to go through environmental review; actually building the project would have required Metro and TriMet to seek out some other funding source further down the road.

But things never even got that far; voters rejected the measure, putting both MAX projects on an indefinite hold. Metro could pursue other funding sources, but Kehe said the agency is choosing to leave both projects on the shelf for the time being, reading the 2020 election results as a signal about voters' priorities.

"The voter approved the affordable housing bond focusing resources on building affordable housing in the region. And then, just one year, I think earlier in 2020, was the approval of the Supportive Housing Services measure," she said. "So those are important priorities for voters and important priorities for Metro, and the transportation measure's failure forced us to put a couple of projects on hold until voters are ready again to talk about future investments in transit."

And even if momentum for a tunnel starts building again, the project's price tag is likely to be a major obstacle. The 2017 TriMet study put the estimated cost of a tunnel at up to about $2 billion, and just two years later, the Metro study estimated the cost at up to $4.5 billion — and both estimates came long before the recent period of post-pandemic inflation.

Ridership is another factor that could decrease the urgency. MAX ridership peaked around 2013 and then plateaued for several years, and came crashing down due to pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and 2021. It's been growing again for the past two years, but still hasn't caught up to pre-pandemic levels. In the long run, Metro planners see the pandemic as a blip rather than a permanent change in the ridership trajectory, but it does suggest that Portland is still a long way out from the kind of capacity crunch that might boost the case for a tunnel.

Why not sooner?

A downtown MAX tunnel might be a pipe dream at the moment, but it's been close to 40 years since the first light rail trains started rolling in Portland, and there have been several big additions during that time — including the Robertson Tunnel through Portland's West Hills. So it's worth asking: Why doesn't Portland have a downtown tunnel already?

If you ask local transportation advocates, it's not for lack of trying. Jim Howell is the director of the Association of Oregon Rail Transit Advocates (AORTA), and he's been involved in Portland transportation planning since the 1970s, when activists pushed the city into ditching the planned Mount Hood freeway in favor of developing what became the original MAX line from Gresham to downtown Portland.

Howell said there was talk of a downtown tunnel all the way back then, but it didn't really fit with the vision for light rail, which was supposed to be more affordable than a full subway system by keeping trains on the surface.

"That's what the original concept of light rail was — you can have a 'metro light' — back when they were starting to do this," he explained. "And they were kind of a combination, because then you could put them on the street. Metro systems, as they should be designed, shouldn't have any grade crossings. And of course, light rail does have grade crossings ... that's why light rail — it's light rail because it was cheap."

Part of the original line was built to run next to I-84, allowing the trains to run at high speed even on the surface, but the downtown Portland portion was built on regular city streets. The western half of the Blue Line was built as an extension off the original line, turning the downtown portion into a slow segment in the middle of an otherwise high-speed line.

The Red and Yellow lines were also built as extensions branching off that core line, so each new addition continued to use the slow downtown tracks, and each one added more train traffic on the Steel Bridge.

Howell and other AORTA members said the biggest missed opportunity for a tunnel was during development of the Green Line, which opened in 2009. The line was going to follow a new route through downtown, and Howell said advocates pushed for that route to be a tunnel underneath 4th Avenue.

But it didn't happen; the bus transit mall on 5th and 6th Avenues was rebuilt with light rail tracks, creating a second surface-level route for the Green and rerouted Yellow lines. That choice also added a fourth line to the Steel Bridge crossing — doubling down on the problem instead of fixing it, in AORTA's assessment.

Howell criticized the system's overall development as too piecemeal, without enough long-range planning to consider how each addition would connect with what was already there, or the constraints it would place on future additions.

As a contrast, he pointed to the rail systems in Seattle and Vancouver, B.C., which mostly run in tunnels or on viaducts rather than city streets. Seattle in particular took much longer to start building its light rail system, but it's catching up — and Howell said the results in both of Portland's northern neighbor cities are better in the long run.

"If you ever want to see light rail as it should have been designed, you go to Vancouver," he said.

Short-term solutions

A downtown tunnel in Portland would help undo some of the constraints that have become baked into the MAX system over time, but Howell acknowledged that it's not going to happen anytime soon — now is the right time to plan for it, he said, rather than building it (he also favors a slightly more direct tunnel route than the one in the TriMet study). But he said there's something else Portland should be focusing on in the meantime.

"You notice we talked about Seattle. Seattle's run every 8 minutes," he said. "We run every 15 minutes. That is a huge difference in ridership potential. Frequency, frequency, frequency is more important than speed, speed, speed."

It gets back to the original problem in the TriMet and Metro studies: the Steel Bridge. The speed problem can't be solved without a tunnel, but Howell argued that the bottleneck problem could be solved with some creative adjustments, like building an above-ground route for the Yellow Line on the inner east side, or scaling back the Red Line to only run between Gateway Transit Center and Portland International Airport.

Those are definitely outside-the-box ideas — TriMet just spent $200 million on a project to expand the Red Line, so it's doubtful the agency would entertain the idea of curtailing it — but Howell said the point is that the priority should be to get lines off the Steel Bridge, because the bottleneck currently places an artificial limit on the frequency of the whole system.

"It's just about clogged up," he said. "And therefore if you start talking about increasing frequency, say down to even at 10 minute headways, that would be 6 trains an hour on each line. You're out of space. You can't do it."