PORTLAND, Ore. — A new report from the Portland City Auditor's office found Portland's code complaint system, which allows anyone to file a formal complaint about the maintenance of someone else's property, has led to a disproportionate number of financial penalties for Portland homes in racially diverse and gentrifying neighborhoods.

It's a story Jerry Duckett knows well. In the North Portland neighborhood of Bridgeton, Duckett is a bit of a local celebrity — thanks to the wall at the front of his property. But it wasn't the wall that got him in trouble with the city. Back in 2007, someone filed complaints about his house. A city inspector found problems with the chimney, gutters, roof and peeling paint.

"I was living in North Portland and I just let it sit for a while. I wasn't living [there]. It needed a lot of repairs," Duckett said.

He ignored the issue and thought it would go away. The inspector issued fines, and when Duckett didn't pay, interest, penalties and fees were added to the fines. Eventually, it was all rolled into a lien on Duckett's property, meaning the city would get paid first if the home ever sold.

"I kept on getting fines. They kept on going up, and I couldn't... it was overwhelming for me so I couldn't keep up," said Duckett.

The fines climbed to a staggering $230,000.

"I didn't believe it at first. Then they said they were going to foreclose on my house," said Duckett.

Bruce Cushman had a similar experience in his gentrifying neighborhood in Northeast Portland in 2008. Someone complained the trim on his house looked bad, and inspectors fined him for deteriorated siding, a broken window and missing trim paint.

"This was the second week of December, and the guy tells me I have to get up on a ladder and paint the facia on my roof," Cushman said. "I told him, 'I can't do that!'"

Cushman said the inspector left, then the fines started. Cushman told KGW he lives on Social Security checks that total less than $1,000 a month — there was no way he could pay the fines. He was cited again in 2010 for doing renovations without a permit. The fines grew and grew. The city put a lien on Cushman's house and the total climbed to $188,000 in fines.

The city's enforcement of property maintenance relies almost exclusively on those anonymous or confidential complaints. This policy dates back to 1914.

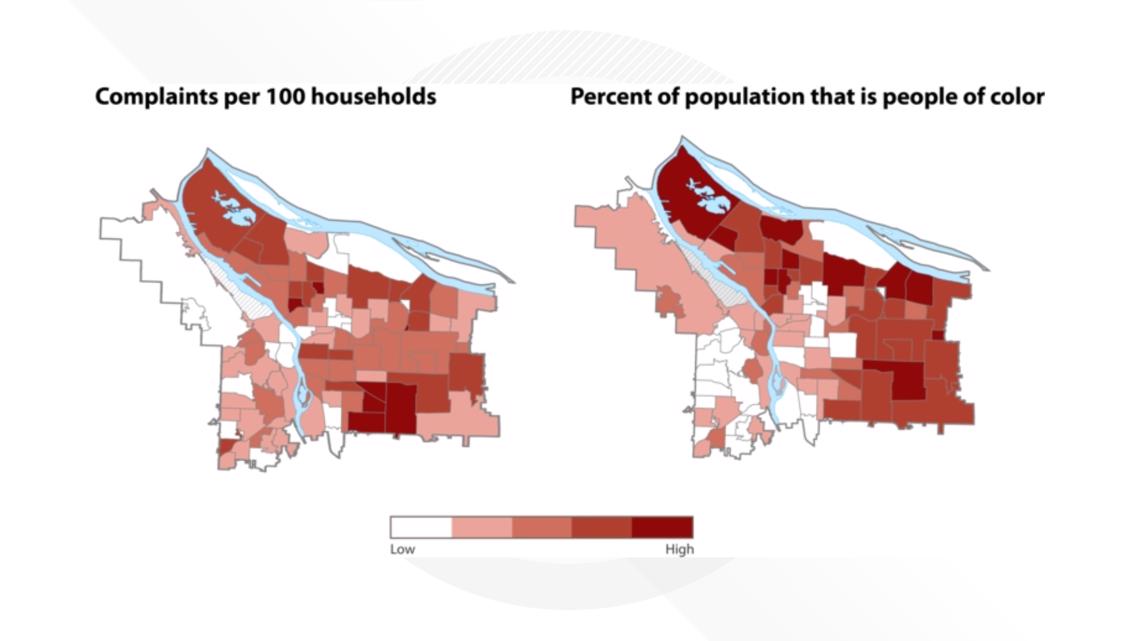

The auditor reviewed more than 15,000 property complaints involving owner-occupied properties over a six-year period. Among many conclusions in the report, auditors found many of the neighborhoods with the most complaints per capita match the neighborhoods that have the highest percentage of people of color living there.

"The danger of gentrification is when the people who lived in that neighborhood before all the services came in, before all the investment came in, are priced out and displaced out of their neighborhood," said City Auditor Mary Hull Caballero. "The city's complaint-driven property enforcement system is adding to the burden of the homeowners already living in that neighborhood. That doesn't mean that gentrification is bad, it's pointing out that there needs to be some steps taken by the city to ensure they are not damaging and burdening people that live in these neighborhoods."

The auditors highlighted another big problem with the enforcement system: the investigators who check the complaints are paid with money raised by complaint fines — that's what funds their budget.

The report also points out the system can be weaponized by angry neighbors and is often enforced inconsistently among neighborhoods, and the city did not seem to notice patterns of unequal enforcement or take them into account.

It also found a complaint-driven system is inefficient, with complaints largely focused on exterior issues like peeling paint or long grass. Analysis found that 30% of complaints were determined to be without merit.

The Bureau of Development Services is in charge of issuing fines. It is reviewing the program now to see if the city should even be involved with complaints that do not involve dangers at the property, and if so, how to fund the program in a different way and make sure it does not unfairly focus on the poor and communities of color.