VANCOUVER, Wash. — The effects of homelessness can be severe, both for those living on the streets and on the communities where they set up camp. Crimes like trespassing, unlawful camping and public storage of property can leave an obvious mark.

Under the typical court system, most people charged with these misdemeanor offenses end up with a day of community service — and importantly, a conviction on their record. Add a warrant and jail time if a defendant doesn't show up for a court date to deal with their legal issues.

What's happening at a place called the Recovery Café on East Fourth Plain Boulevard in Vancouver is different. For the past year, the city of Vancouver has been dealing with low-level crimes most often committed by those who are homeless in a unique way. Its Community Court, along with numerous partners including the Clark County District Court, is providing more assistance than punishment in an effort to break the homeless cycle.

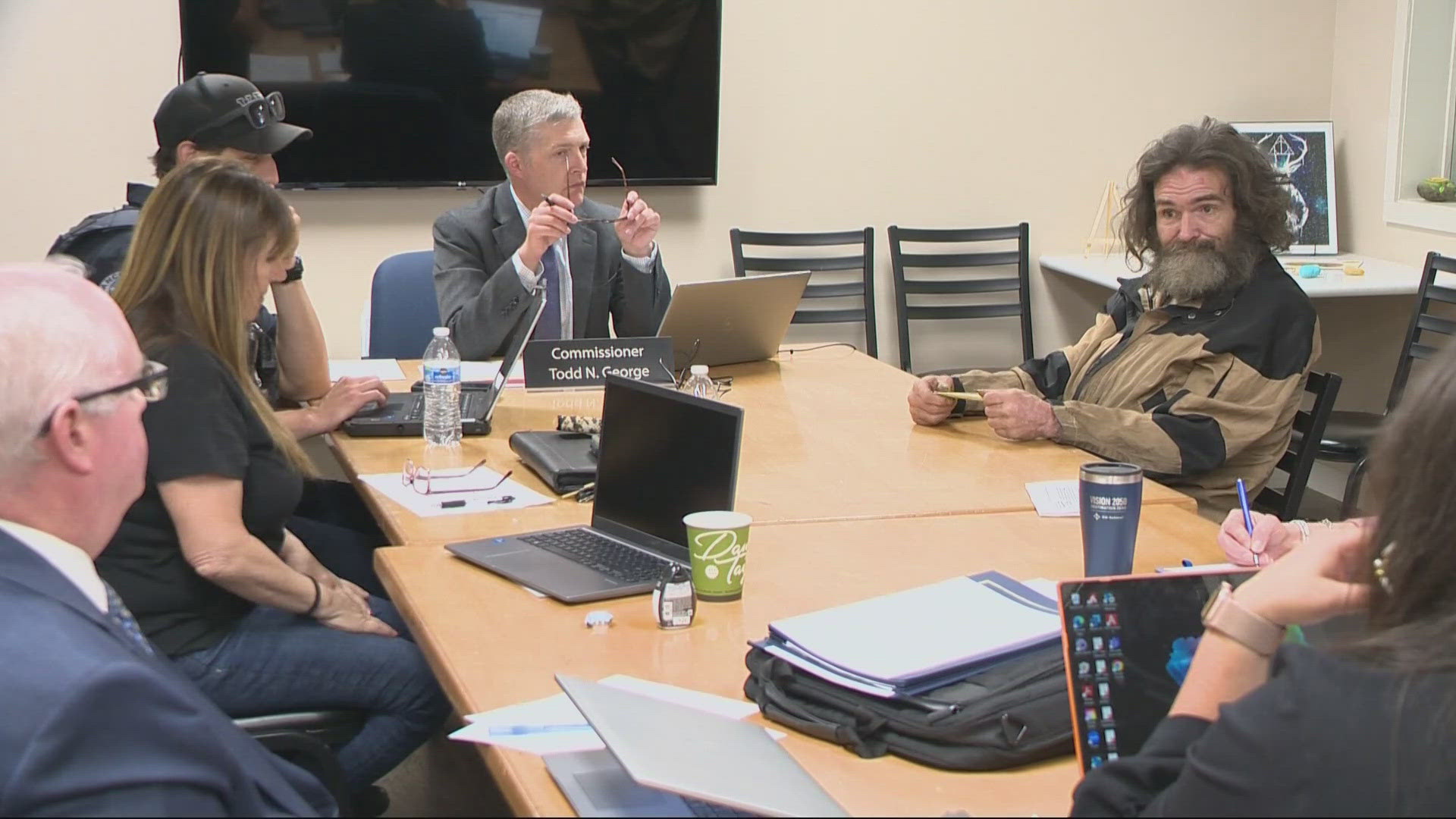

Community Court takes place every Monday afternoon in a cramped conference room at the nonprofit Recovery Café, which serves as the host location. A court commissioner is in charge, and a whole host of people are there to help.

Kevin McClure is a city prosecutor for Vancouver. He's been at it a long time.

“This is 30 years of me prosecuting crimes and this is one of the most innovative programs I’ve ever been a part of. So, I’m really excited about the court. Within the course of two months, you can see some people's lives really change,” said McClure.

That's because this court doles out more opportunity than punishment.

“It's rewarding, and like I said, it's like the first time in my career where we're making some concrete steps to actually assist people," said criminal defense attorney Christie Emrich.

Emrich is owner of Vancouver Defenders, a public defense firm. She's spent a lot of time in all kinds of courts.

“I think this one is meeting people where they're at. The criminal justice system is not designed to help people,” said Emrich.

And that, Emrich said, is why this is so refreshing and powerful.

The difference in tone is immediately apparent when these cases come up, as exemplified by an exchange KGW witnessed between a woman participating in the program and a member of the court; Sheila Andrews, encampment response coordinator for the city of Vancouver.

“You look like you've had a rough weekend," Andrews said. "Mother’s Day is a bittersweet day for a lot of women.”

“It was a really rough day yesterday,” the participant admitted.

“I'm proud of you for showing up.”

“Thank you," the woman responded. She was clearly struggling, but she showed up.

“Are you ready for something different?” Andrews asked her.

“Oh yes, lord yes.”

“Are you so close?"

The participant nodded in the affirmative, but said, “And the other part of me is standing on the ledge and I’m behind me and ready to shove myself off the ledge.”

"OK, as long as you're getting closer," Andrews said. “It's not easy and it's scary, and there's a lot of things that happen, but it's worth it.”

As long as the participant makes progress, there is support available for her — with mental health, substance abuse issues and housing. It even includes the smaller things, like getting a valid driver's license.

Not all issues can be solved here. But a lot of them can.

Representatives from various agencies sat at the Community Court table, and also in the main space at the Recovery Café. And the café serves lunch. Instead of avoiding court, many participants are eager.

Every participant is required to do community service, usually cleaning up homeless camps, sometimes taking care of the very mess they made. Those who graduate have their cases dismissed.

“And I'm going to admit, at first, I really didn't think it was going to work, but it did. I'm here,” said Butch Wood, who graduated from the program a few months ago.

Now he comes back to support others, grateful for the opportunity he received.

“Here, they treat you like an individual," Wood said. "In court you don't get treated like an individual, you get treated like a statistic.”

Community Court is set to expand from half- to full-day sessions in order to serve more defendants. Both the prosecutor and defense attorney are on board.

“This is a weird little court we have, so kind of for the first time, I think we are we're more in line than we are opposed,” said Emrich.

“I think as long as somebody is legitimately trying, we're willing to give them as many chances as it takes,” said McClure.

So far, 86 participants have opted into community court, and nearly half of them have graduated. Some are still in the process, and others opted out or didn't make it through the program. At last check, about 50% of graduates have been able to get into some type of housing.

The KGW Solutions Project is our commitment to report on ideas and strategies that address important issues in our community. We want to hear from you about solutions. Contact us at solutions@kgw.com.