As child care costs soar, how is Oregon trying to solve the crisis?

Oregon families have felt the strain, especially working parents, as child costs soar to equal the cost of rent — leaving many struggling with what to do.

The high costs of child care can be debilitating on many families, and an unavoidable hurdle for parents that need to work.

So, when Natalie Kiyah, a single mother of four in Portland, first got access to public child care funds through Oregon’s Employment Related Daycare Program (ERDC) program, she said it was life-changing. But now, having lost that support once already, a whole new set of worries has set in.

“I understand now why people stay in the cycle — it’s such a cycle of poverty,” she said. “Because you can’t get too far over the limit or else you lose all support.”

In March 2023, Kiyah received an “exit letter” from the state because her annual income had crossed over the salary cap for the program — by $2,000. The loss of the child care subsidy, she said, was debilitating for her family. With more than $1,600 of her paycheck each month going toward child care costs, Kiyah moved her family into a homeless shelter to regain some stability.

Kiyah switched from a career running her own photography business to a job at the Oregon Food Bank that brought down her income enough to requalify for the ERDC program.

The subsidy program now covers 100% of Kiyah’s daycare needs, which includes infant care for her youngest daughter, preschool for her son and after-school care for her eldest kids, twin second graders. Without it, she said child care would cost 75% of her monthly take-home paycheck.

Solution: Income subsidies

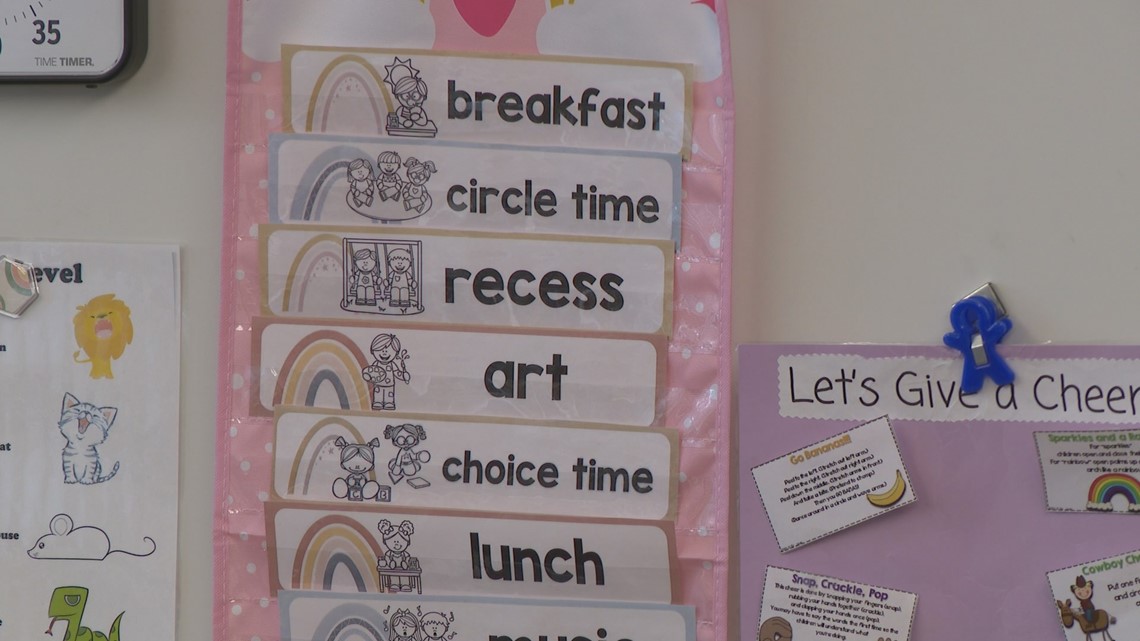

Oregon has a network of state-supported child care programs, from Preschool Promise, Oregon Head Start and Early Head Start to Baby Promise, that offer government-subsidized child care with a low copay — typically less than $10 per month.

All of them have eligibility requirements like the ERDC program, which is only available to families who are working, in school or receiving aid from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. It also has set income requirements. To qualify, families must earn less than double the federal poverty level to first enter the program. To maintain eligibility, families must continue to earn less than 250% of the federal poverty level, which is about $105,686 for a family of five.

Kiyah hopes one day to break away from the cycle. She said she doesn’t want to live in a homeless shelter forever and would like to be able to get her own place. But for now, she must rely on the subsidy.

“If I get kicked off of ERDC again, I don't know what I will do about that,” Kiyah said.

This is why Candace Vickers, director of Family Forward Oregon, has been lobbying for universal child care.

“I believe what we need is a universal solution to child care here in Oregon,” Vickers said, “that has a dedicated revenue, that doesn’t have to wait every two years to figure out if it’s going to be able to pay its bills.”

ERDC currently pays almost the entire cost of child care for 16,446 low-income families, with 2,800 families on the waitlist. In January, the Department of Early Learning and Care, which administers the program, projected that it would run out of money in January 2025, six months before its next budget takes effect in July 2025.

In the recent legislative session, Oregon lawmakers approved $171 million for ERDC as part of a collective spending bill to sustain the subsidy program.

Solution: Preschool For All

One child care solution Multnomah County has been exploring is Preschool For All, approved by voters in 2020. It’s essentially aiming to create a public school network but for early education.

The county-led program started to offer free preschool to 3 and 4-year-olds in 2022. So far, it has supplied child care to nearly 1,400 children in Multnomah County with the goal to create 11,000 publicly funded preschool slots by 2030.

Audreona Mullens, a mother in Portland, said she was thankful when Preschool For All was introduced. With child care expenses so high, Mullens said she and her husband could only afford to send her son to daycare part-time, limiting the hours she could work.

Before Preschool For All, Mullens and her husband lived with his parents to afford child care. She said her entire paycheck would go toward covering child care costs.

Now, with her son in a Preschool For All program, Mullens said she can go back to work full-time and her family can grow again financially.

Unlike ERDC, Preschool For All doesn’t have any income eligibility limits. The only two requirements are that children be 3 or 4-year-olds by the start of the school year, Sept. 1, and have a parent or legal guardian living in Multnomah County.

However, the program has had some growing pains and pushback. Director for Preschool For All Leslee Barnes said there has been an expectation that the program should be expanding faster. But the slow movement toward offering preschool for every family isn’t for the lack of funding.

In the first two years of the program, 2022 and 2023, the county raised approximately $386 million through income taxes. The funding structure for the program stems from an income tax on Multnomah County’s highest earners, which affects approximately 36,000 filers out of the roughly 200,000 who file taxes in the county, according to a county economist.

Barnes said different obstacles have plagued the program — infrastructure and workforce.

"No matter how many slots we offer, if there are not buildings that are adequate to implement this, it really doesn't matter," she said.

Currently, the program is prioritizing families who struggle to access child care. Most families who have been able to get a slot in Preschool For All have an annual income at or below 350% of the federal poverty level. And the demand for free access for all families is clear, Barnes said. Around 96% of available slots this year have been filled — and each time more slots open, twice as many families apply.

Preschool For All plans to add about 1,000 to 1,500 slots a year to meet its goal. So far, this has mostly been done through subsidizing smaller preschool providers to convert them from private pay to public access. Barnes said they give providers around $15,000 to $21,000 a year per public slot they offer. The program is doing the same to also convert private or public slots that have been traditionally half-day programs into full-day publicly funded ones.

The other way the program is expanding is by creating new child care slots. Barnes said Preschool For All providers will be able to apply for funds to expand their care center or open a new location. The condition is any slots created using Preschool For All funds can only ever be public-access. This is to prevent any providers who may switch back to private pay from taking those free slots away.

But growing the number of program slots has proven more difficult than originally thought. In 2022, Preschool For All adjusted its overall and yearly target goals by about a thousand slots. When the program was originally approved, it planned to have between 1,500 to 2,000 free child care slots this year.

Preschool For All said the overall targets were adjusted to reflect the impacts of COVID. In 2022, there had been a 25% reduction in early childhood providers in Multnomah County compared to 2020, the program said.

“While COVID forced the program to make a short-term revision to its targets, it still is planning to provide universal preschool access in 2030 as originally planned,” a county spokesperson said. “The yearly seat goals will not be adjusted again.”

Solution: Employer care

Another child care solution comes through employers. The Biden administration's CHIPS and Science Act requires private companies who receive over $150 million of federal funding to provide affordable child care for their employees.

Semiconductor companies are expected to add 3,000 jobs in Oregon in the coming years, state economists said. Plus, the expansion of chip factories will create hundreds of construction jobs, which could put a drastic strain on the child care system.

In mid-March, the Biden Administration awarded Intel up to $8.5 billion in CHIPS and Science Act Funding — and with that comes requirements to provide accessible child care for construction workers and workforce.

Earlier this month, Gov. Tina Kotek signed a bill that essentially creates a framework to help Intel, and any other future companies receiving CHIP Act funds, on how to provide the required child care.

Family Forward Oregon advocated for the bill. Vickers hopes that it will provide funds for some smaller, more independent providers to expand and be able to provide the child care that will be needed when the semiconductor plants expand.

While the CHIPS Act funding doesn’t solve the child care woes for every family, it does offer an interesting incentive: What if companies seeking federal or state funds were required to provide an affordable child care option for their workers? It’s clear that the ability to find and afford child care impacts an employee’s ability to come to work and stay there.

“The cost of child care is crippling without the government subsidy,” Kiyah said. “I just really hope that lawmakers are listening and are just understanding how intense.”

The KGW Solutions Project is our commitment to report on ideas and strategies that address important issues in our community. We want to hear from you about solutions. Contact us at solutions@kgw.com