It was business as usual on a dreary Friday afternoon in Woodburn 10 years ago.

Outside the West Coast Bank on Highway 214, drivers zoomed by on their evening commutes. The Pacific Northwest's ubiquitous winter rain shrouded the city.

Inside the bank, signs of the looming holiday dotted the lobby — a Christmas tree, poinsettias and festive decorations.

Earlier, an ominous phone call led police to a green box tucked into the bushes outside the bank.

Investigators carried it into the bank where, at 5:24 p.m., a bomb inside the box tore the building apart, killing two law enforcement officers, seriously maiming the Woodburn police chief and sending a father and son to Oregon's death row.

The aftermath of the bomb also threatened to tear the community apart. People mourned the loss of the officers, their sense of security and safety. The criminal investigation and ensuing trial lasted years.

Anger and hatred could've easily filled a community shocked by something of this magnitude, said Woodburn City Administrator Scott Derickson.

Derickson had only been on the job a few weeks when an officer knocked on his door the night of Dec. 12, 2008, about an hour after the bombing.

Everything after that felt like a blur, he said.

He remembers meeting with Mayor Kathy Figley to discuss what the city's message would be in the wake of the tragedy.

"The mayor looked at me and said, 'We are going to focus on love. We're going to tell the community that this is the time to stand together'," Derickson said.

And, the mayor added, "We're going to tell the community that Woodburn is better than this."

The day of the bombing

That Friday began to turn ugly when a man called a Wells Fargo Bank in Woodburn, telling an employee that everyone in the building would die if they didn't leave immediately.

He instructed the employee to retrieve a disposable cell phone, which was discovered outside near a garbage can. A green metal box was also found in the bushes at the nearby West Coast Bank.

Investigators deemed the call and the green box to be a hoax.

Oregon State Police Senior Trooper William Hakim decided to take the box inside the bank for further examination. Accompanied by Woodburn police Capt. Thomas Tennant and Chief Scott Russell, Hakim began dismantling the box.

Bank employee Laurie Perkett remembers Hakim saying, "Okay, I got it."

Video footage of the moments before the explosion shows Tennant and Hakim kneeling next to the box amid the computers, desks and Christmas decorations.

Suddenly, the footage goes black.

The explosion ripped through the bank, killing Hakim and Tennant, seriously injuring Russell and wounding Perkett.

Additional surveillance captured debris blown across the room and plumes of gray and white smoke.

Detective Sgt. Nick Wilson, who was ordered outside by Russell to do a perimeter check moments before the explosion, heard the blast, saw a flash of light and rushed in the lobby to find a war zone-like scene.

He and Sgt. John Mikkola found Hakim and Tennant, almost unrecognizable and already dead from the explosion, then discovered Chief Russell bleeding profusely from his leg.

Wilson used his belt as a tourniquet on the chief.

Perkett, who was walking toward the door as the device exploded, was hit with a piece of shrapnel.

It wasn't until later, when she was talking with first responders, that she looked down at her bloodied leg and realized the shrapnel had cut her to the bone.

The explosion shut down nearby highways and officers filled the area, a cluster of strip malls and residential homes just south of the Interstate 5 interchange.

News of serious injuries filtered out into the community.

The next day, state police identified the men killed as Hakim, a certified hazardous device technician from Keizer, and Tennant, a Woodburn police captain who joined the department in 1980.

Aftermath and investigation

Hundreds of investigators poured into Marion County to track down those responsible.

Lead investigator Marion County Sheriff's Detective Mike Myers told the Statesman Journal in 2013 that 265 investigators from multiple agencies worked on the bank bombing case.

City administrator Derickson said in the hours and days after the bombing, hundreds of agencies, police departments, community members and businesses offered their help.

"The city was stumbling," he said. "We lost two-thirds of our leadership and half of our police department. They were taken out of action as either witnesses or because they were impacted or they were wounded."

He recalls getting a random call on his cell phone from Seattle officials, who offered to send an officer and patrol car down to help cover shifts.

The outpouring of support was overwhelming.

"It's something I'll never forget," Derickson said. "They really held the city up when we could have actually fallen down. The wheels could've come off, but they didn't because people rushed in and propped us up until we could stabilize and move forward."

Back then, current Woodburn Police Chief Jim Ferraris was with the Portland Police Bureau, which provided resources for the law enforcement response and hospitalization of Russell.

He said people in the policing community made a commitment to support Woodburn as much as possible.

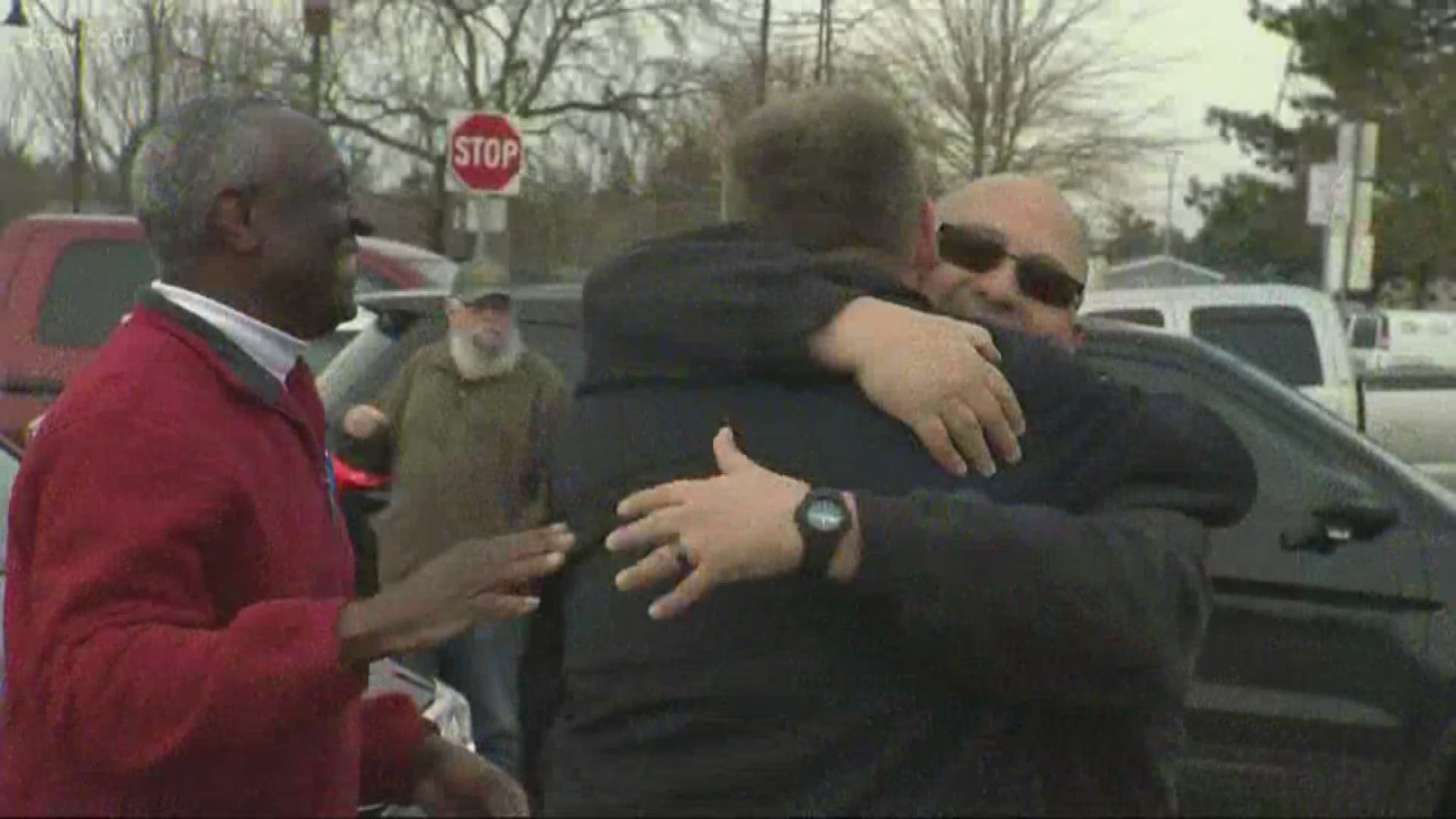

Ferraris said he watched as the community strengthened and residents spurred into action, rather than descend into hate and fear.

Trial draws national spotlight

The investigation led to the arrest of Joshua Turnidge at his Salem home. His father, Bruce Turnidge, was arrested at his residence in Jefferson, where investigators said they found materials matching metal bomb fragments found at the crime scene.

According to prosecutors, the father and son concocted the bomb threat to fund their failing biodiesel business. They also have argued that the pair shared anti-government beliefs and were fearful that the election of President Barack Obama signaled a trend toward the government clamping down on gun rights.

The Turnidges' trial lasted almost two months and attracted massive public attention.

Weeks of witness testimony, video footage of the carnage and forensic evidence was presented.

Both Turnidges maintained their innocence and pointed to each other as the sole culprit.

The jury deliberated for only four hours before unanimously finding the men guilty on all 18 counts against them, including aggravated murder, attempted murder and unlawful manufacture of a destructive device.

The Turnidges showed little reaction as the verdict was read before a packed courtroom.

The men were later sentenced to death and remain on death row due to the state's ongoing moratorium on executions.

Their death sentences were upheld by the Oregon Supreme Court in 2016.

Former Marion County District Attorney Walt Beglau said the bombing was "the most complex criminal investigation and prosecution in the modern history of Marion County."

He also said the impact of the tragedy on the community was immense.

Ferraris said about one-third of the current police department were employees at the time of the bombing.

"It stays with them," he said. "It's something they never forget. We vowed in the police department to never forget Tom Tennant, to never forget Bill Hakim, and never forget the injuries that Scott Russell and others endured as a result of that event."

Russell, who lost his right leg in the blast and underwent dozens of surgeries, continued as police chief until his retirement in 2015.

Derickson remembers the crowded vigil held in downtown Woodburn the weekend of the bombing — people of all different cultures, languages and religions, who gathered to hold candles and pray.

"The message was that hate did this," he said. "We are not going to hate anybody. We are going to love each other. We are going to be a community. The community is going to stand up and make sure that the future is better than this and not worse."

For questions, comments and news tips, email reporter Whitney Woodworth at wmwoodwort@statesmanjournal.com, call 503-399-6884 or follow on Twitter @wmwoodworth