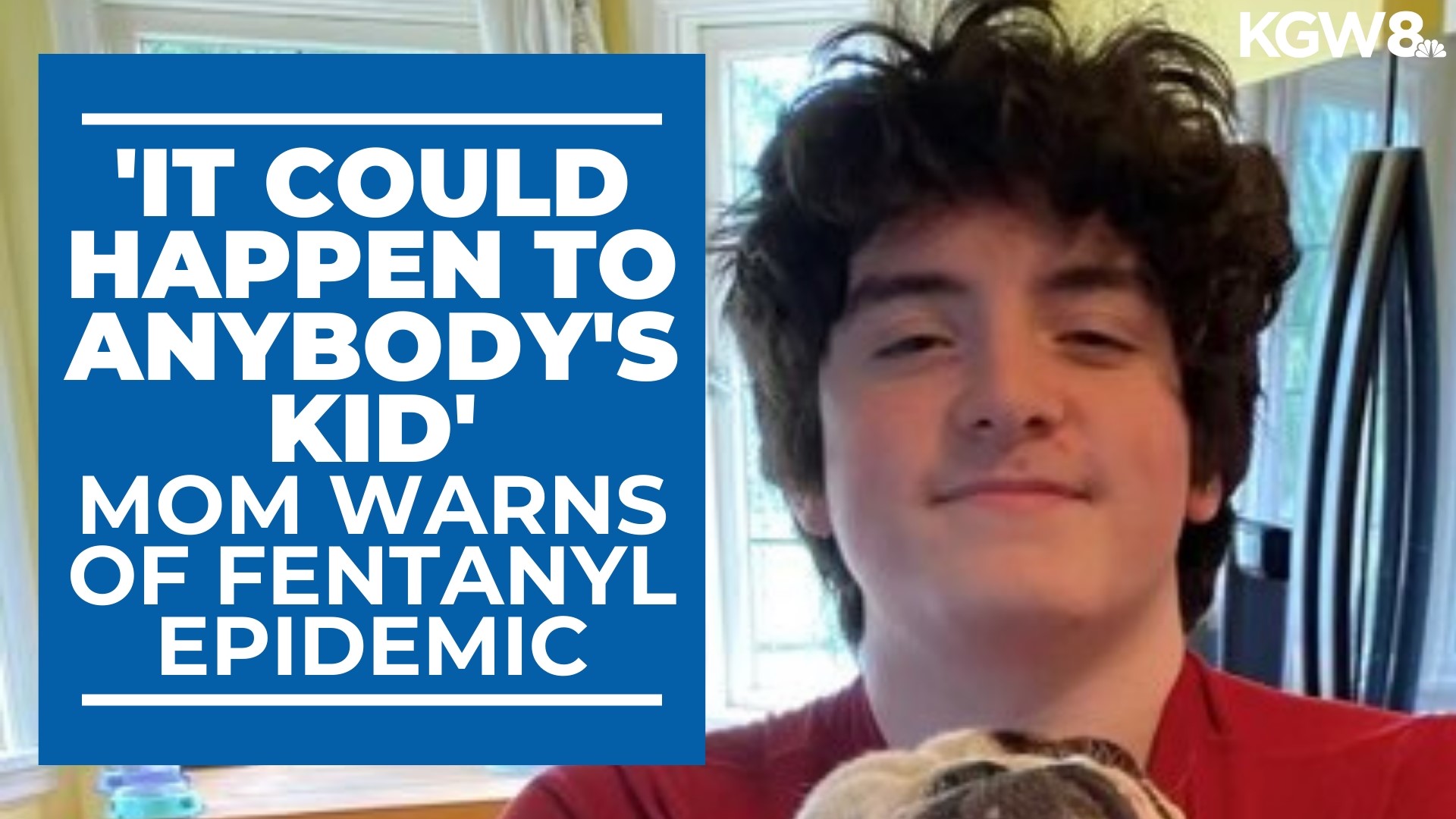

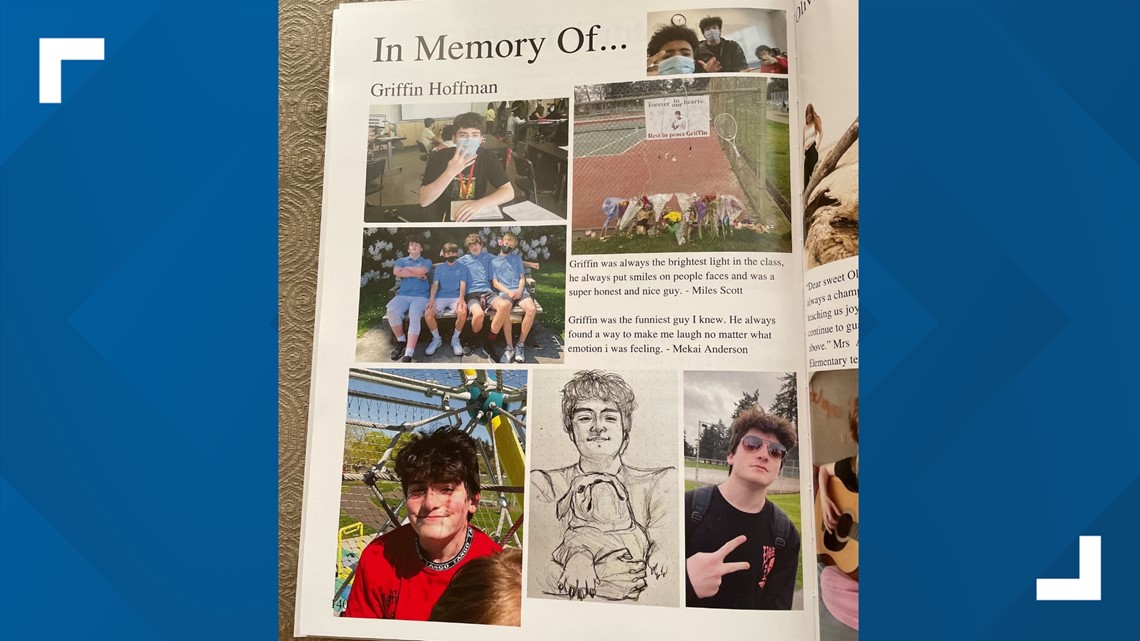

PORTLAND, Ore. — Kerry Cohen struggles with the loss of her teenage son, Griffin Hoffmann, nearly every moment of every day. His humor, she says. His energy. His hugs.

“I miss every last thing about him,” Cohen said. “It’s really difficult to talk about.”

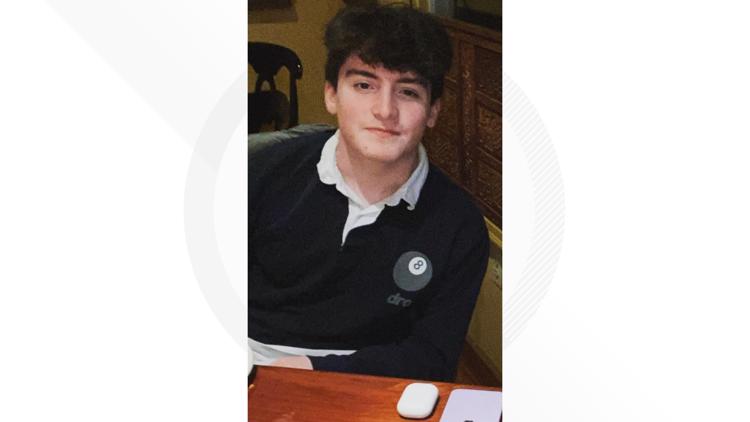

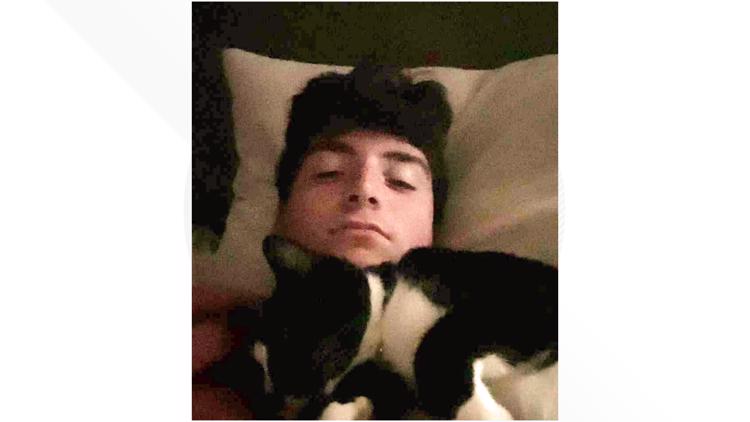

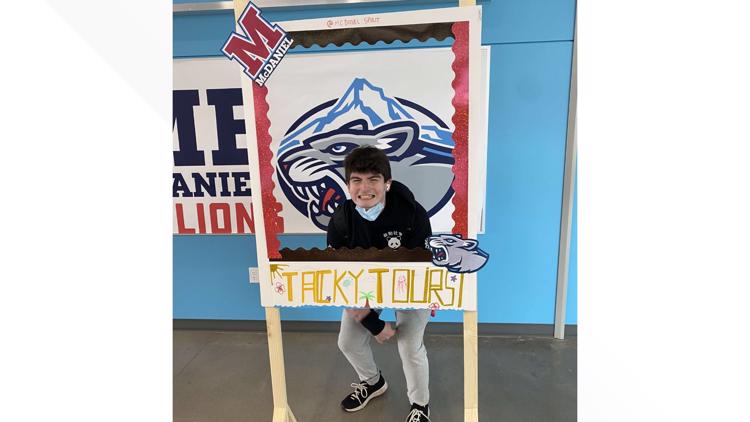

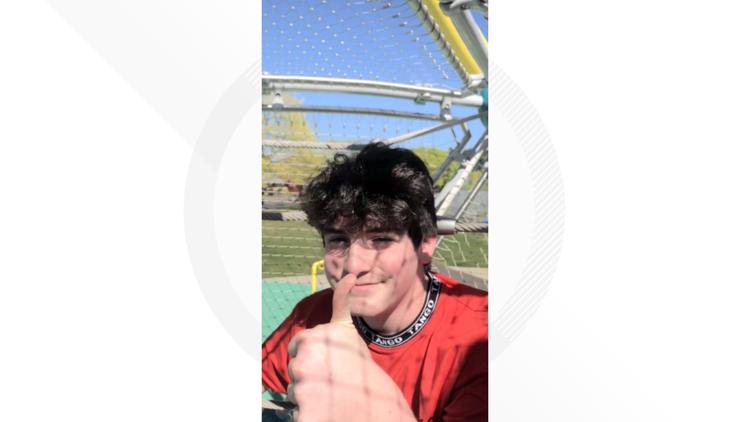

Despite the pain, Cohen wants to tell her son’s story. It's a story about how the kid she describes as “extremely witty and funny” grew into a 16-year-old tennis star at Northeast Portland’s McDaniel High School.

“He had the biggest heart,” Cohen remembers. “He cared so much about people.”

It's a story about how he defended people who were bullied. And about how he was, in some ways, emotionally mature beyond his years — yet in others, still a kid at heart.

“I made a decision early on that I want my son’s name out there,” Cohen says. “I want as many people as possible to care about him and feel heartbroken about him.”

On a Monday morning in March, Griffin’s father, Michael, went down to his son’s basement bedroom to wake him up for school.

Griffin was sitting at his desk. His laptop was still open.

“His dad threw open my bedroom door and said, ‘Kerry, get up – something’s wrong with Griffin,’” Cohen recalled.

She raced downstairs.

“The first thing I saw was his hand, because his dad was holding it, trying to find a pulse ... and there was no pulse.”

Investigators would later confirm that Griffin had overdosed on the synthetic opioid fentanyl, which is up to 100 times more powerful than morphine.

Cohen uses a different word: poisoned.

“There is no redemption,” she said. “The worst thing in the world happened to me. The worst thing in the world. Every parent’s biggest fear is what happened.”

'A regular teenager'

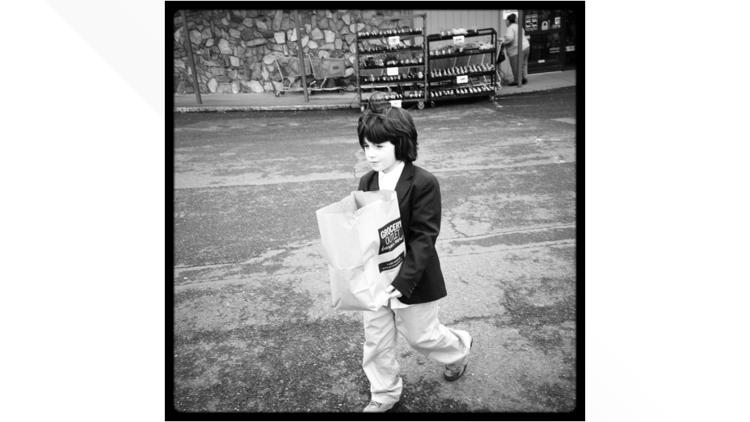

Griffin made the varsity tennis team at McDaniel as both a freshman and a sophomore. According to his mom, he was a “superstar,” who loved both the strategy of the game and the camaraderie of his team.

“He was all about his friends, and they did what every teenage boy is doing,” Cohen said.

That included going to the movies on weekends to see “The Batman,” playing video games at all hours of the day and night, and plenty of what Cohen called “experimentation.”

Story continues below.

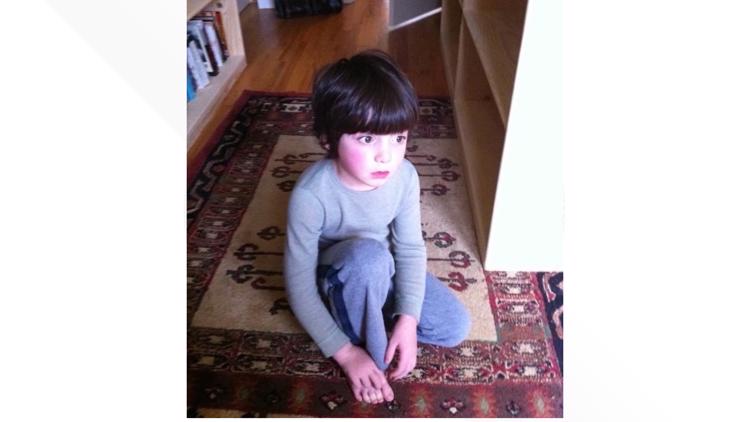

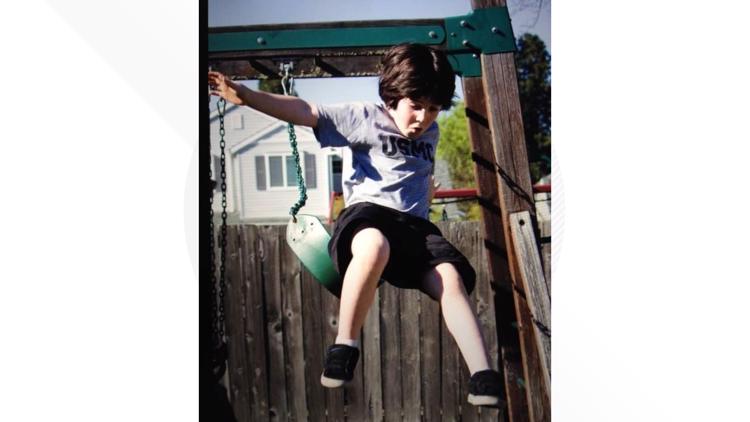

PHOTOS: Griffin Hoffmann

The pandemic hit Griffin especially hard, his mother said. He’d had anxiety since he was young. Cohen, who is a licensed professional counselor, remembers her son asking her to take him to a therapist.

She and Griffin’s father, who had separated prior to their son’s death, were “really involved, good parents,” she said.

They’d had multiple conversations with Griffin over the years about the dangers of drug use — including things she said Griffin knew to never, ever try, like heroin and meth.

Like many parents, Cohen said, she and Griffin’s father were trying to find that tricky balance between being involved in their son’s life and invading his privacy. Most of all, they wanted him to feel comfortable coming to them to have challenging conversations.

“We made it clear to him, you’re not going to get in trouble,” Cohen said. “This is what matters, is discussion.”

Cohen knew Griffin had tried marijuana. At the therapist’s office, she found out Griffin had taken a few other substances; including Percocet, one of the name brands for the opioid oxycodone. He wrote the drugs down on the therapist's intake questionnaire, Cohen said, and didn’t try to hide it.

Cohen doesn’t know where her son got the fentanyl pills that killed him, but she’s sure Griffin wasn’t taking them regularly.

“He was just doing normal experimentation like any other kid,” she says. “He was just like a regular teenager.”

The morning she and Michael found their son, Cohen says she already had a sense of what had happened.

“I figured in the beginning … he must have taken something and not known,” she recalled. “Right away [the police] found those blue pills."

RELATED: 'We're not good to go right now': CDC shows many teens still struggle with pandemic-related trauma

‘A merchant of death'

The pills found in Griffin’s bedroom would turn out to contain fentanyl. They were manufactured to look like prescription pills, down to the finest details: pale blue in color with an “M” imprint on one side, and the number “30” on the other.

And within a matter of weeks, according to federal court filings and Griffin’s mother, investigators were able to trace that bag directly back to a 24-year-old alleged drug trafficker.

Manuel Antonio Souza Espinoza of Vancouver, who prosecutors describe in court documents as being a “merchant of death,” now faces federal charges that include conspiracy to distribute and possess with intent to distribute fentanyl, resulting in death.

If convicted, Espinoza faces a mandatory minimum of 20 years in prison on that single charge alone, and a maximum of life imprisonment.

Espinoza’s lawyer, Larry R. Roloff, did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

The U.S. Attorney’s office for the District of Oregon, which is prosecuting the case, alleges Espinoza was the “third level” supplier in the chain, meaning the counterfeit M30 pills made their way through two other dealers before reaching Griffin Hoffmann.

Espinoza was arrested, records show, on March 31, 2022, with the help of a “cooperating defendant” who pretended to go through with a pre-arranged drug buy from Espinoza near Portland International Airport as law enforcement looked on.

It’s unclear if authorities have directly linked the “cooperating defendant” to the pills that killed Griffin.

U.S. Attorney Scott Erik Asphaug declined to comment about the case, citing the ongoing prosecution — though he indicated, as of early June, no one else had been charged in connection with Griffin’s death.

Cohen said she also wants the street level dealer who handed the pills directly to her son to be held responsible.

“We asked [prosecutors], ‘Who is the last person who knew what these [pills] were, that they probably might kill.' And they told us, 'Every last one.’”

Fentanyl ‘explosion’ hits Oregon

According to Asphaug, cases like the death of Griffin Hoffmann are no longer outliers, but what Oregon’s top federal prosecutor calls an “epidemic.”

“Last year alone, we had 11 deaths [from fentanyl] in the state of Oregon from young people under the age of 18,” Asphaug said.

That’s more than double the number from 2020, which was five, according to data from the Oregon-Idaho High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program (HIDTA).

In 2019, the number was zero.

Most of it is coming from Mexico and traveling up the I-5 corridor, Asphaug said. Fentanyl, in the form of counterfeit prescription pills, is both cheap to manufacture and easy to transport.

From there it makes its way into existing drug distribution chains, reaching teens through social media platforms that experts say include Snapchat, Instagram and Telegram.

According to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the amount of fentanyl seized in Oregon from 2019 to 2021 increased by 1,891%.

The DEA calls it a “flood.” Asphaug uses the word “explosion.”

“We can’t prosecute our way out of these cases,” Asphaug said. “We also need the public to know how dangerous this drug is.”

Danger ‘wasn’t clear’

Within days of Griffin’s death, public health and law enforcement agencies began issuing urgent public warnings about counterfeit prescription pills.

Adam Skyles, the principal at Griffin’s school, Northeast Portland’s McDaniel High School, acted even faster.

That’s in part because Griffin was the second student in less than 24 hours to die from taking a counterfeit prescription pill that turned out to be fentanyl. Both the Portland Police Bureau and the U.S. Attorney’s office indicate that this investigation is ongoing and do not believe Espinoza was connected to the other student’s death.

“The immediate response is to try to keep everyone safe,” Skyles recalled.

After learning about both deaths and meeting with police the Monday that Griffin died, Skyles posted a video on Instagram warning his 1,400 students about the counterfeit pills and asking them to turn them in, no questions asked.

When I asked Skyles if any students had taken him up on his offer, he stuck to his promise to them that he wouldn’t be sharing details.

“We wanted this to be something that was between the school and the student, that they felt safe and protected,” he said.

While naloxone — a medication that can reverse the effects of an opioid overdose — is now readily available at McDaniel, the biggest change since March, Skyles said, has simply been awareness.

“It wasn’t clear, the level of danger and how prevalent [these pills] are,” Skyles said.

A staggering scale

To get a first-hand glimpse, we visited a sprawling warehouse in an industrial section of Northwest Portland operated by the Portland Police Bureau.

Inside the narcotics storage vault, Jacob Gittlin, a property and evidence supervisor with PPB, showed us shelf after shelf where they keep seized fentanyl.

From buckets to baggies, there’s so much evidence that fentanyl needs to be stored in its own section. There is enough of the drug in PPB's warehouse to provide hundreds of thousands of fatal doses, and Gittlin said that it needs to be handled with care.

“Due to the extraordinary dangers … we have to keep it separate,” Gittlin said matter-of-factly.

And there’s another reason fentanyl, in pill form, is widely understood to be such a threat: example after example shows it’s nearly impossible to tell counterfeit prescription pills made of fentanyl from the real thing.

“They may think they’re ordering Percocet, they may think they’re ordering Xanax, and they’re not,” said Lieutenant Chris Lindsey with PPB’s Narcotics & Organized Crime Unit.

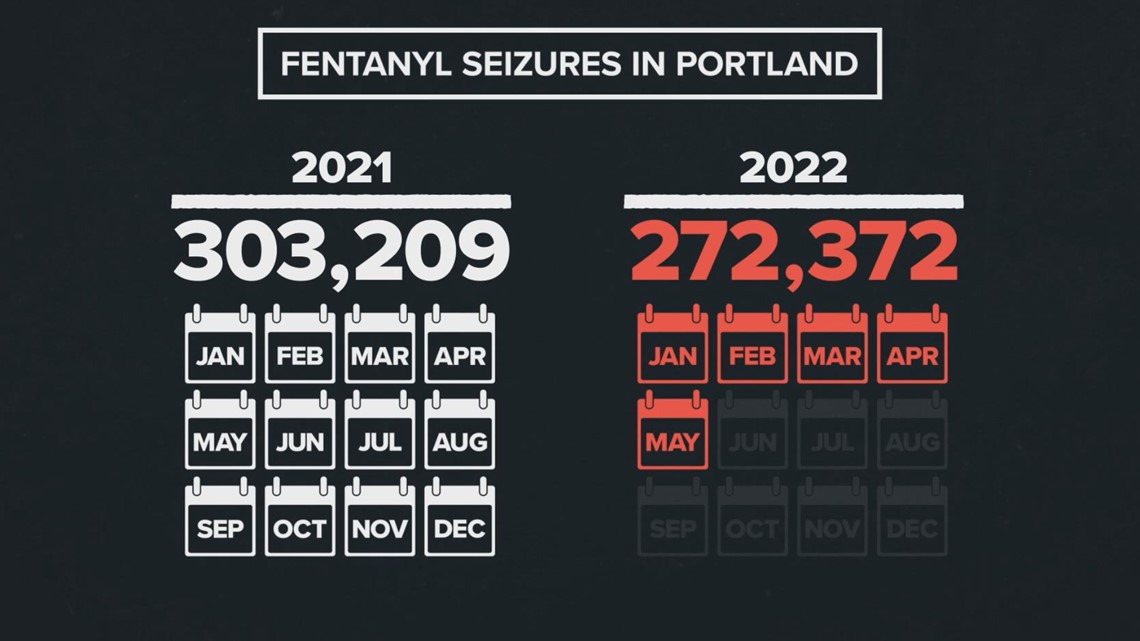

And the scale is staggering. When it comes to confirmed or suspected fentanyl, in the first five months of this year, Lindsey said PPB has already seized nearly 90% of what it had recovered in all of 2021.

Most of it has been in the form of little blue M30 pills, though he cautioned that the manufacturers are changing tactics. They’re now sending fentanyl in powder form, Lindsey said, as well as in bar-shaped pills meant to mimic Xanax.

And there’s one more point Lindsey wants to drive home. Public awareness campaigns like the DEA’s “One Pill Can Kill” actually underestimate fentanyl’s dangers. That’s because it takes just a few grains, less than can fit on the tip of a pencil, to prove fatal.

Lindsey said that because of the manufacturing process of the counterfeit pills, it’s important to tell exactly how much of the drug is in a single pill.

“We’re seeing people OD on half a pill, sometimes potentially a quarter of a pill,” he said. “We need anyone we can to get the word out.”

Remembering the boy with the big heart

Three months after Griffin’s death, a white tennis racket pinned to the fence at Glenhaven Park marks the spot where the budding superstar won so many matches.

Messages on a poster board are fading away. Flowers have long dried up. But for Cohen, the pain and the grief endure.

Right now, she told me, she can’t find meaning in Griffin’s death — because the thing she says she wants most, can never happen.

“The fact that it happened to my kid is evidence it could happen to anybody’s kid,” Cohen said.

Her immense sense of loss is coupled with anger directed at the people in the drug supply chain she believes are responsible for her son’s death.

Espinoza is next due in court in July, records show. Cohen has been asked to write and deliver a statement to help sway a federal judge to keep the alleged trafficker jailed while he awaits trial.

Griffin’s mother says she isn’t looking for remorse or accountability. For her, neither of those is enough. Instead, it’s what she calls “hopeful thinking.”

“That he could become a person that maybe would make sure that other people wouldn’t do what he did,” she said. “And to change the world with his bad decisions.”

It’s still far too painful for Cohen to look at pictures of her son. Instead, she has a constant and faithful reminder: a tattoo of a griffin she got 10 days after he died.

She cried the whole time, she said, and it wasn’t because of the pain from the needle. The griffin is on her wrist.

“It just helps to be able to look down, and be able to see it,” Cohen said. Her “life pulse,” she calls it.

“He was so much more than one tiny thing he did that ended his life,” she said. “I want people to remember his humor and his heart.”