PORTLAND, Ore. – Portland has 10 percent more homeless people now than in 2015, according to the 2017 Multnomah County Point in Time Homeless Count.

But while the county’s overall homeless population has grown, the number of people sleeping outside dropped by about 12 percent. For the first time since the homeless count began in 2005, there were more people sleeping in shelters than on the streets.

It’s a gratifying result for Portland and Multnomah County, which invested $20 million more in homeless services last year; however, the good news comes with clear caveats.

“It’s good to see the needle moving,” said Denis Theriault, spokesman for the county’s Joint Office of Homeless Services. “There’s more work obviously to be done.”

The initial results from the 2017 homeless count were released Monday. The count this year took place in February instead of January, due to severe weather. The full report is expected in July.

The count itself is a difficult undertaking, with staff and volunteers visiting every shelter and homeless camp they know of and learning as much about every homeless individual as they can. It only counts people in the winter, when more people are in shelters and therefore easier to find. It doesn’t account for the homeless swell Portland experiences in the summer due to a transient population that temporarily makes the city home.

The number of homeless people in Portland is almost certainly higher than what the count found.

Key takeaways

Initial findings show changing trends among demographics. While some populations are finding housing, others are increasingly becoming homeless.

In 2015, the homeless count found 3,801 people sleeping on Multnomah County Streets, in shelters or in transitional housing. In 2017, that number rose to 4,177.

This year there were 1,668 people who were “unsheltered” -- sleeping outside in vehicles, abandoned buildings, tents, and in homeless camps such as Dignity Village or Hazelnut Grove (federal definitions of homelessness require structures in homeless villages to count as “unsheltered”). That’s down from 1,887 in 2015.

The sheltered homeless population, meanwhile, was up by 31 percent, from 1,914 to 2,509. That is mostly attributed to the city and county opening more than 600 new shelter beds since the last count.

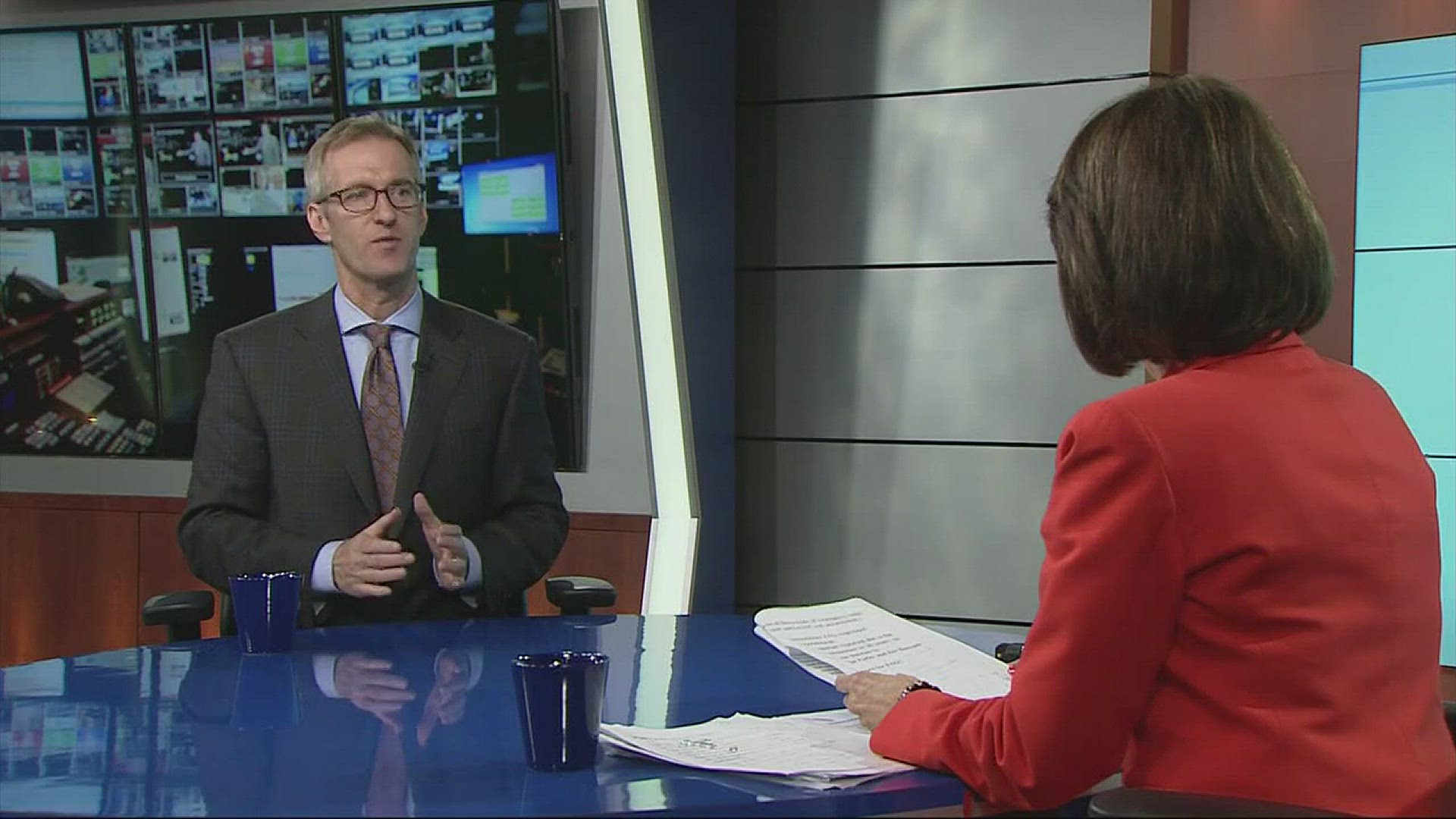

“We’re continuing the good work we’re doing around shelter, around permanent housing, around the support services like mental health services and addiction treatment programs,” said Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler.

Marginalized populations were still hit hardest by homelessness. There were more women, seniors, disabled, chronically homeless and unaccompanied youths during this count than the last count.

Disabled people, in particular, make up a large portion of the city’s unsheltered homeless population. Seventy-two percent of people living outside have either a mental disability, chronic physical condition, or substance-use disorder.

The city now has more chronically homeless people than before – the number of chronically homeless people in shelters nearly doubled since 2015.

The city made strides to house all of its homeless veterans, but while many veterans found housing a new wave of veterans became homeless. That means the homeless veteran population is virtually unchanged, from 422 in 2015 to 446 in 2017, although more veterans were in shelters instead of on the street.

More families are also in shelters now than two years ago, with about half as many families living on the street as in 2015. In addition, African Americans and women saw their unsheltered numbers drop.

Domestic violence is a significant factor in homelessness for women. More than half of homeless women reported being victims of domestic violence.

The count also found about 300 more Native American homeless people than in 2015. However, the joint office said Native Americans may not have been properly counted in 2015.

Homelessness still visible in Portland

Compared to other cities, Portland is making more progress getting its homeless population off the streets and into shelters and temporary housing.

King County (Seattle), Alameda County (Oakland, Calif.) and Los Angeles County (Los Angeles, Calif.) all saw spikes in their unsheltered populations -- 45 percent, 61 percent and 38 percent, respectively.

But in Portland, 1,668 people living outside is still more than anyone wants, and the city concedes that while the unsheltered homeless population is down, homelessness is arguably more visible than ever. While the city and county have shown some enforcement of outdoor camping laws, they also have attempted to let homeless people safely sleep outside.

“There’s a visibility challenge right now,” Theriault said. “Last year’s attempt to balance enforcement with safe sleep was challenging for a lot of folks. There were a lot of people staying in tents, and tents are more visible.”

Rising rents also aren’t helping Portland address its homeless crisis. The county noted that on average, rent has risen 20 times faster than income since 2015.

“Like communities up and down the West Coast with rapidly rising rents and stagnant incomes for our lowest-income residents, this year’s count shows, once again, that thousands of our neighbors experience homelessness on any given night,” said Marc Jolin, director of A Home for Everyone and the Joint Office of Homeless Services.

The count is required every two years by law for counties to receive federal funding for homelessness.

The county is planning another homeless count in 2018, and will start counting homeless every year so it has a more accurate picture of who is homeless in Multnomah County.

“We’re off to a good start but the job is not done,” said Wheeler.