PORTLAND, Ore. — A Portland Presbyterian church made the final vote Friday to give land back to the Indigenous-run Future Generations Collaborative to build Barbie’s Village — a tiny home village and early childhood center for unhoused Indigenous families.

“It's a beautiful day for land to be returned to tribal communities,” Anna Allen, Shoshone-Bannock, tribal affairs advisor for Multnomah County said Friday.

Future Generations Collaborative, an Indigenous-led organization that strives to generate healthy and healing Indigenous communities, has served the needs of urban Native people in the Portland area since 2012.

Organizers say it’s been a dream in the works for over two years now to build between six and 10 tiny homes along with a resource center that will provide wrap-around services for Indigenous families experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity.

As of Friday night, that dream is finally becoming a reality. The congregation voted to gift the land and building of the former Presbyterian Church of Laurelhurst to Future Generations Collaborative — 135 in favor and 24 opposed.

“This is a huge win for us, for our community, and really, for all of Indian Country,” said Jillene Joseph, Aaniiih citizen, engagement lead for Future Generations Collaborative and executive director of Native Wellness Institute.

Rev. Aric Clark said the move is an important part of healing the relationship between the church and Indigenous peoples.

"If we do land acknowledgments, but are afraid to do land back, then that is a form of taking the Lord's name in vain,” Rev. Clark said. “It's essentially saying holy words, without having any meaning or intent to actually back them up with the right action. So if we are serious about trying to understand our history, and our complicity, but also trying to just build good relationships for the future, it's not just about the past, it's also about the present and the future.”

Barbie’s Legacy

The project is named after Barbie Shields, a citizen of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs and dedicated natural helper — a role central to the mission of Future Generations Collaborative — who worked with the organization for five years to address public health disparities in the Indigenous community, particularly among those experiencing houselessness on their homelands.

This was something Shields and her family understood first hand.

Kenneth Shields, Barbie’s husband, said the couple experienced homelessness early in their marriage, when they had young children. Because of that experience, Shields, Anishinaabe and Sioux, said it was Barbie’s vision to create a safe place for Indigenous families with small children to begin their journey to collectively repair and heal from homelessness and the lasting impacts of colonization.

“That was always one of Barbie’s concerns – wanting to help our people that were living on the streets,” said Jillene Joseph, executive director for the Native Wellness Institute and a partner with the Future Generations Collaborative. “She always felt how ironic it was for Native people to be homeless on their own homelands.”

But she didn’t live to see her vision come to life. In 2018, Barbie Shields died after suffering a brain aneurysm. She left behind her husband, her four children and her community.

“Her death just had a profound impact on the other elders and natural helpers — on all of us,” Joseph said. “We wanted to do something to keep her legacy alive and to honor the work that she was doing.”

With the help of Barbie’s husband, Future Generations Collaborative brainstormed the idea of Barbie's Village.

The years-long process to get to this point — where construction for the tiny home village might finally begin — involved a lot of red tape, along with important relationship building.

Allies

In 2021, the Presbytery Leadership Commission created the Barbie’s Village Task Force to work with Future Generations Collaborative, Leaven Land and Housing Coalition and the Westminster Presbyterian Church. They shared a goal: working together to address and fulfill a need in the community.

"This is one of the first times that I have ever experienced allies totally stepping up for me, and it's been amazing," Joseph said.

The Barbie’s Village Task Force, led by Reverend Chris Dela Cruz, made a motion to gift the former Presbyterian Church of Laurelhurst, in exchange for $1. Dela Cruz said members of the task force felt strongly that returning the land to Indigenous stewardship was an opportunity for the church to begin the path to repatriation and reconciliation.

“By giving the land that was formerly the site of Laurelhurst Presbyterian Church to Future Generations Collaborative for the creation of Barbie's Village we are making our commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous people concrete, proving that ours is not a dead faith without works,” Rev. Dela Cruz said before the Presbytery of the Cascades during a virtual meeting on Friday.

“We are also taking part in one of the most inspiring models of community care for one of the most urgent crises of our time,” Rev. Dela Cruz added.

The project also garnered support from the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, whose members have ancestral ties to the land known today as Portland.

“We congratulate the Future Generations Collaborative on the hard work to make this land back gift happen and we fully endorse the gift and the good work that will follow,” Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy wrote in a letter of support. “Further, we raise our hands to the church and praise their efforts to uplift the Native community; this is a win for all of us to celebrate.”

Funding

Barbie’s Village is set to open amid a backdrop of unprecedented funding available to address homelessness and housing instability from Multnomah County, where Portland is. The county closed the June fiscal year with $42 million in unspent dollars generated by a voter-approved supportive housing services measure.

That same month, the regional government Metro announced it had collected an additional $50 million in unexpected money from the measure, by hitting up taxpayers in arrears. The annual tax could bring in a total of $2.4 billion by 2031.

In early September, as part of an administrative corrective action plan to address the unspent money, the Multnomah County Board of Commissioners approved $17.6 million in one-time funding for new shelter sites, rental assistance and more.

And last month, Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson announced an emergency measure to get that money into the hands of the nonprofits the county contracts with to address homelessness. As part of that package, she allocated $300,000 to assist with start-up costs at Barbie’s Village.

“I’m using executive authority to drive action and change on the ground so we’re making sure our investments reach the people who need them the most right now,” Multnomah Chair Vega Pederson said.

It’s a start, but $300,000 is far below what organizers say they will need to complete the project.

Organizers are hoping to build tiny homes that meet the needs of Indigenous parents and children. That means homes with indoor plumbing and heating as well as outdoor child playscapes to create a safe and permanent place to assist and foster a deeper connection to land, each other, and the great community and culture.

The project will need a lot more money to make this a reality. Jillene Joseph said it will take about $5 million to fully fund Barbie’s Village. She said organizers submitted information to the county showing that need. But the county responded with $300,000.

“We never technically said ‘We need $5 million,” Joseph said. “We said, ‘Please fund us.’ And here’s the budget the architects gave us.”

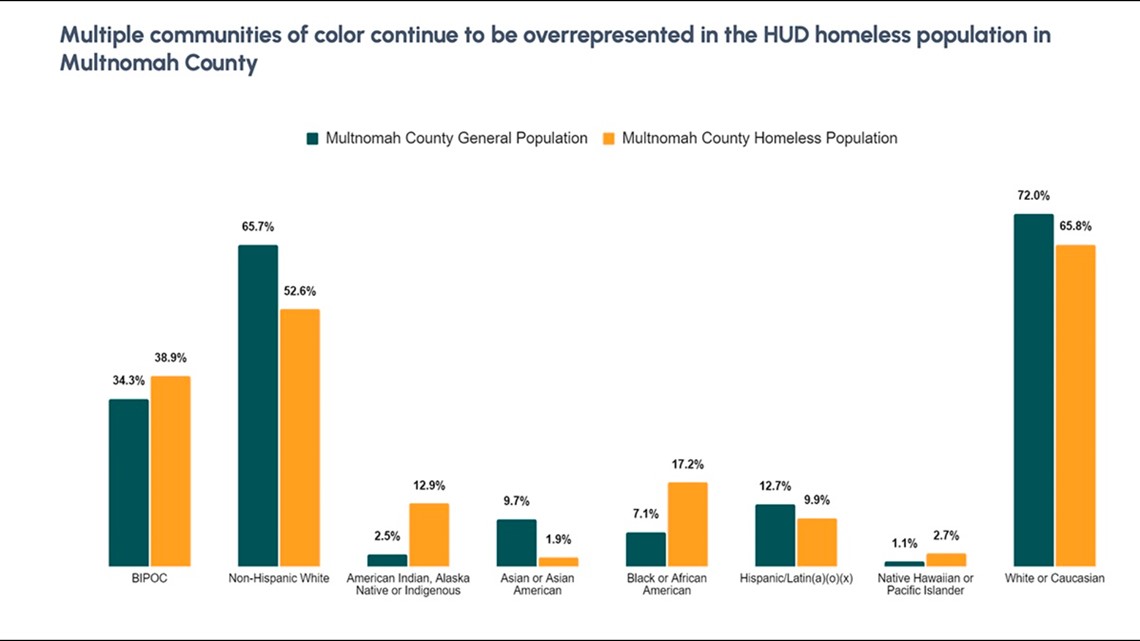

Indigenous people were the group most disproportionately represented in the county’s 2022 count of unhoused people — the most recent count for which data on racial disparities is available. In the November 2022 point in time count, 12.9 percent of those counted identified as Indigenous, American Indian or Alaska Natives, even though Indigenous people make up 2.5 percent of the county’s population.

That reality, along with the county’s full coffers, has left some questioning why the county didn’t provide more funding to Barbie’s Village — a project that directly serves those most disproportionately represented among unhoused people in the Portland area.

“Multnomah County allocated $300,000, which is low for what we need,” said Chenoa Landry, Education Lead at Future Generations Collaborative. “We are trying to fund self-sustaining tiny homes, with plumbing and electricity.”

Anna Allen, tribal affairs advisor for the county, said the county sees the project’s value.

“I think the county does definitely value and recognize that Native people are overrepresented in our houseless community, and we know culturally responsive housing strategies are critical, bringing our Native community members to safety in a way that they define for themselves,” Allen said.

Joseph says she hopes the county will contribute more in the future.

“The county is actively engaging in the decolonizing work that we have been helping to lead them through,” Joseph said. “That gives me hope that this $300,000 is just an initial investment to help us get things off the ground for Barbie's Village.”

The next budget cycle represents another opportunity for Future Generations Collaborative to apply for additional money, according to Stacy Borke, Multnomah County senior policy advisor on housing and homelessness.

“This was not a one and done opportunity for Future Generations Collaborative or any community seeking support in addressing the crisis on our street,” Borke said.

During the meeting Friday night, the vote was not unanimous. Some members of the church’s board of trustees wanted to attach an agreement about what to do in case Barbie’s Village fails. Joseph said ideas like that complicate efforts to obtain funding.

"Money is there for this kind of stuff," Joseph said. "We might not be the experts at getting that money, but we want to find it. Nor do we have all these critical eyes judging us and watching everything – waiting for us to fail. It's this delicate balance we have to do."

While there might still be hurdles to overcome, Joseph said Friday’s vote is a win for all involved.

“This is land back,” she said. “This is literal land that goes into the hands of Native people.”