The Portland Bureau of Transportation is working on a more permanent solution to the issue of proliferating "abandoned" RVs parked around the city.

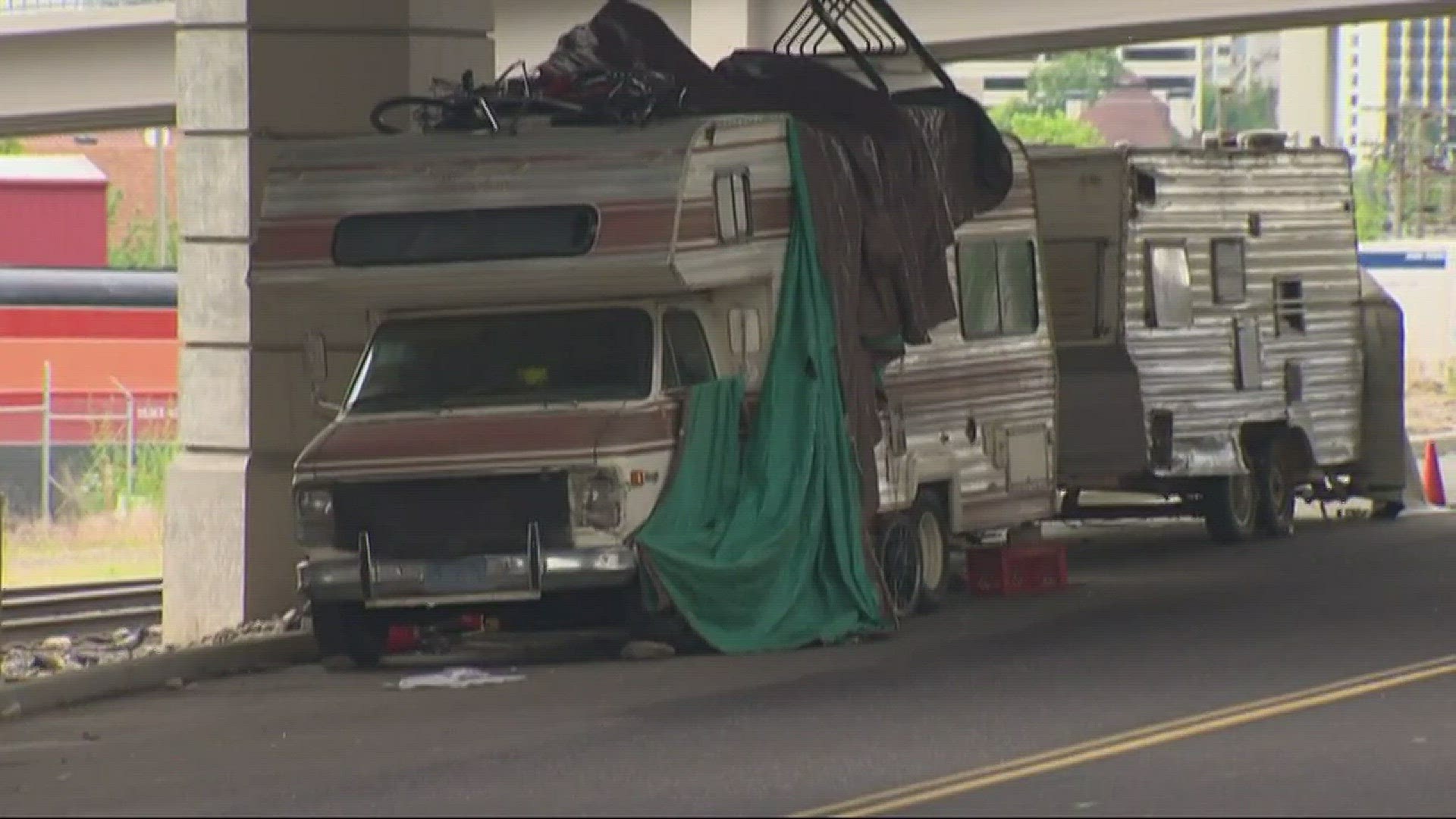

The problem is, often these vehicles aren't actually abandoned – many of them are being used as housing and bring issues like trash, drug use and general unsightliness to the neighborhoods where they're parked. The city has heard complaints of RV occupants trespassing in neighbors' yards and leaving used needles lying outside the vehicles.

"We've been getting a massive amount of constituent concerns about what we're calling 'derelict RVs'," said Brendan Finn, chief of staff for PBOT Commissioner Dan Saltzman.

"There are unlawful acts happening in and around them, issues like drug paraphernalia and human waste. We consider these to be a health hazard for the community."

PBOT Public Information Officer Dylan Rivera said the city receives more than 100 abandoned vehicle reports each day, which include these RVs and other broken down cars.

PBOT does have regulations in place when it comes to parking RVs and other large vehicles: They may be parked in commercial areas for no more than four hours, residential areas for up to eight, and adjacent to or across from public parks with a permit from the city.

However, enforcement of these rules is based largely on complaints. And, based on state law, Portland has had a policy of only towing truly abandoned vehicles, which are clearly no longer drivable or in use. If someone lives in the vehicle, it's not considered abandoned, making the RV problem even more complicated.

The rules are beginning to shift, though, in response to the hundreds of RVs popping up around town. Often, the vehicles arrive in conditions that leave few clues as to how they could have traveled to their new parking spots in the first place. The issue may, in part, be a result of ordinances passed in San Francisco and Seattle that make it illegal for RVs to park on most city streets, while the rules are less stringent in Portland.

Many of the impounded RVs have had Washington license plates, Finn said.

Now, PBOT is dealing with the RVs through a new program it's calling "Community Care Tows." Written tow warnings will be left on reported RVs for 72-hours, giving occupants a chance to move them. If the vehicle remains after the warning period has ended, police will come to help remove any inhabitants of the vehicle before it is towed.

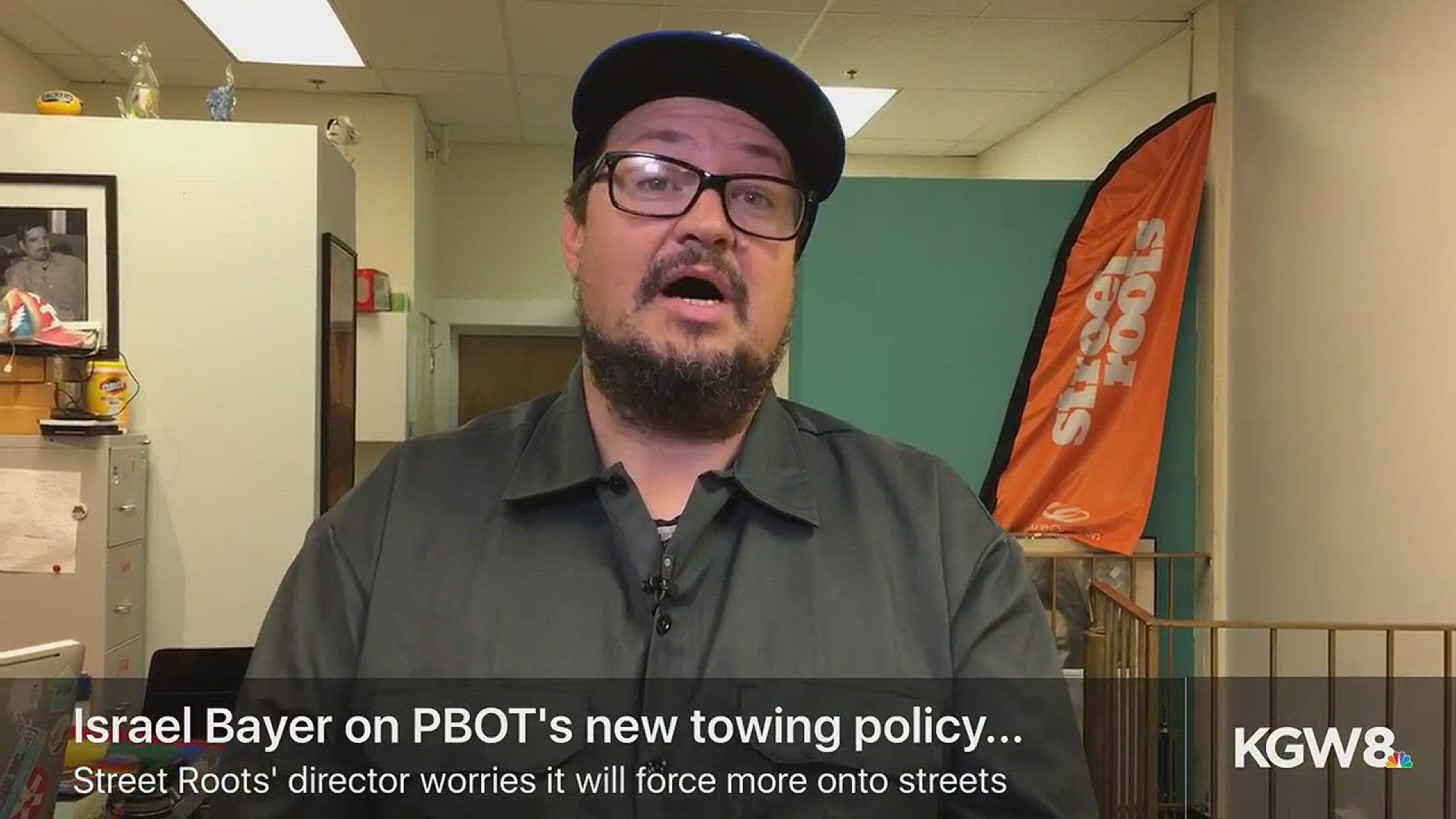

Some worry that solving the problem of illegally parked RVs may exacerbate Portland's homelessness problem.

Rakiya Birge is an advocate for the nonprofit Human Solutions, which provides shelter and services for Portland's homeless community. She said the organization often gets calls from people living in their vehicles, asking for referrals to services or simply for information about where they can park their RVs.

"Unfortunately, we can't help them when it comes to wondering where they can park those vehicles," Birge said.

But by towing illegally parked RVs, the city may be "taking away the only thing that these people have," she said, adding that Human Solutions can refer those living in vehicles to one of its two shelters, assuming they meet certain qualifications and there is space available.

"They should really be able to park their RVs anywhere, so long as they aren't doing anything else illegal, because it's what they consider home."

For its part, PBOT is trying to tackle the problem in a "humane and strategic way," Rivera said.

The city has developed the One Point of Contact system for businesses or citizens to report a suspected homeless camp. Officers investigate the claims as well as those of abandoned vehicles and, if they find people camping in a neighborhood or living in a vehicle, will make an effort to connect those people with homeless social services.

Finn said the same happens through the "Community Care Tows" program; if RV inhabitants stay on scene after the vehicle is towed, officers work to connect them with housing or drug treatment programs.

In recent months, the city has towed so many of these abandoned RVs — which aren't as easy to dismantle and recycle as cars — that the towing companies it contracts with are running out of space to take them in and store them.

"We've frankly been overwhelmed by abandoned vehicles, and especially RVs," Rivera said.

As the city examines where to go next, it is considering ways for Portlanders to dispose of unwanted RVs that don't include abandoning or giving them away to members of the homeless community. This could include a program through which the city would collect old RVs and oversee their proper disposal.

"It’s been an amazing increase observed on our streets, creating a real livability issue for citizens and businesses," Finn said. "We need to do something about this and get these RVs off the streets."

Clare Duffy covers government and general business for the Portland Business Journal.