'You take care of Jesus': Corvallis church helps homeless despite angry neighbors, legal confusion

"Safe Camp" is a village that serves as a tangible representation of the church’s newfound mission: to help Benton County’s homeless.

Shrouded in the pinkish hue of the rush hour's setting sun, car after car cruised by the First Congregational United Church of Christ on Thursday.

Suddenly, one let out a honk.

"That’s not a supportive honk," said Reverend Jen Butler.

The senior minister was standing in the Corvallis church's front lawn.

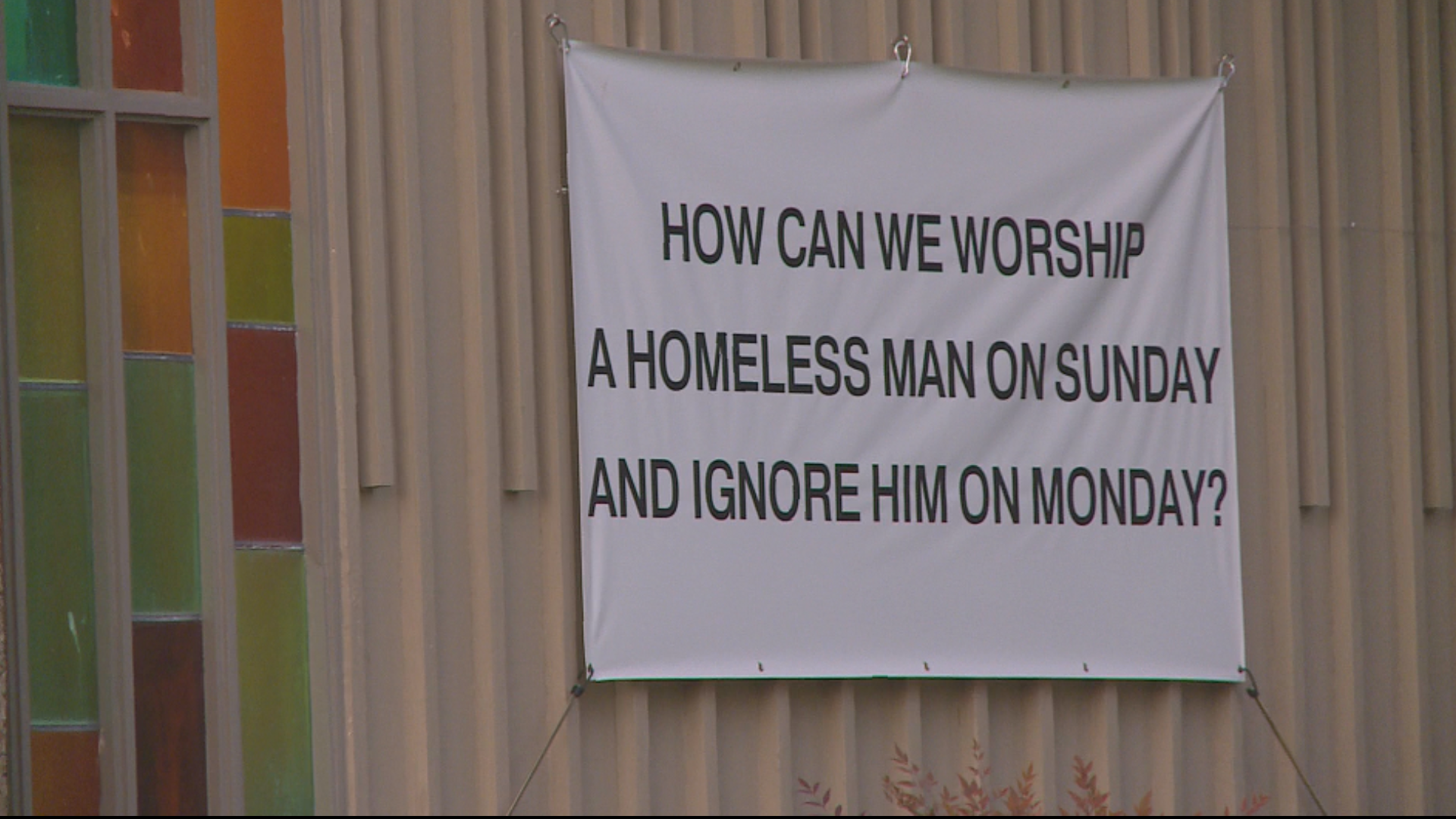

Behind her a large, white banner nailed to the building's facade offered the first clue as to what she was talking about.

It read: "HOW CAN WE WORSHIP A HOMELESS MAN ON SUNDAY AND IGNORE HIM ON MONDAY?"

From the road, the weatherproof banner is, by design, easy to see.

The tents, tarps and homeless men and women living in them, though, are camouflaged by the wooded area just west of the church’s main driveway.

Dubbed "Safe Camp," the months-old village serves as a tangible representation of the church's newfound mission to help Benton County's homeless.

"I don't think any of us imagined becoming real players," Butler said of the issue. "We had no idea there were that many people in the forest."

The Forest

The church’s 1.34 acres of land is divided almost down the middle by that main driveway, which leads to a rear parking lot.

The woods that begin on the western side extend beyond the property line, onto a neighbor's land.

Local authorities tell KGW people have been illegally camping in those woods for at least a decade.

"The issues that happen there sometimes ebb and flow, sometimes seasonally," said Benton County Undersheriff Greg Ridler on Friday. "People often find a good location for them to set up homeless camps, and then other people come in. We become aware of it. We respond. It's cyclic."

Locally referred to as "the Christmas tree farm," the neighboring property is actually just vacant land, owned by Corvallis businessman David Lin.

Ridler said a few years ago, Lin asked authorities to help him clear homeless camps from the woods on his property, which resulted in deputies citing campers for trespassing.

Lin declined to comment for this story, except to say via phone that he "respects [the church's] wish."

Butler said she learned of the routine this past summer, when one citation hit closer to home.

"One Sunday morning we were getting ready for worship," she said. "A gentleman walked into the church and asked if I knew that someone had been arrested for trespassing on our front porch the night before."

Authorities have not confirmed that specific citation.

Butler couldn't let it go.

"It made me curious, you know? Why? Why would someone be arrested for trespassing? The owner of a property usually has to complain, and we certainly hadn't done that," she said. "And we began by just asking law enforcement not to [cite] people."

Word spread fast, and people desperate for a permanent place to sleep came running to secure a spot.

"Within 24 hours of having taped off our property line for law enforcement, we had 23 people seeking safe sleeping space on our property," Butler said.

Butler and her congregates were overwhelmed.

She said they'd already set up a port-a-potty on the property, assuming people camping next door would use it. "But the reality of 23 people showing up asking for shelter? No, we did not anticipate it."

But, she recalled, a consensus quickly emerged.

"From the moment those folks showed up, the congregation just said, 'Well, absolutely,'" she said. "When Jesus shows up on your front door, you take care of Jesus."

The camp was there to stay, with the population capped at nearly two dozen.

That is, assuming they could make it legal and get neighbors on board.

"It's complicated."

When Benton County officials first got wind of the church's undertaking, they hoped it would be a temporary solution to the ongoing problem of illegal camping in the woods.

"Because it was short-term and not permanent at that time, we viewed it as not subject to the county's zoning regulations," said Greg Verret, community development director with Benton County.

Verret said in an interview Thursday, officials initially gave the church permission to keep the camp intact for 90 days.

As that deadline grew nearer, it became clear campers didn't want to move and congregates didn't want to force them to.

"We discussed what potential there was for making this a longer-term, more permanent facility," said Verret, adding that church leaders and members have been communicative and cooperative throughout the process.

Even though the desire was clear, the path moving forward was not.

"It's complicated," Verret said.

Complicated, because the church's property exists in two municipal jurisdictions, with the building sitting on Corvallis city land and the wooded area containing the camp on Benton County land.

The western edge of the church's driveway, in large part, marks the dividing line.

The idea of zoning a county property for temporary housing that's run by an organization with a city address was the epitome of uncharted territory, Verret said.

Months later, they're still working on it.

"One potential way for the church to get approval for this is to obtain conditional-use approval to establish church activities on the vacant parcel that's in the county zoning," he said, adding that's one of a few options they're examining.

Undersheriff Ridler agreed that question of jurisdiction creates confusion, adding that trying to respond to calls about criminal activity on county land owned by a Corvallis church is "… just a mess."

A saving grace in the process, though, came unexpectedly from the Oregon state legislature.

House Bill 2916, which went into effect in June, amended an already existing state statute, allowing local governing bodies to authorize campgrounds inside urban growth boundaries, classifying them as "transitional housing" for the homeless.

It goes on to say those campgrounds "may include yurts, huts, cabins, fabric structures, tents and similar accommodations" and it adds the agency or organization who set up the campground may provide parking, access to water, toilets, showers and other services.

It also leaves room for the Oregon Health Authority to step in later and develop "public health best practices" for those facilities.

Verret said Benton County is watching other municipalities around the state to see if and how they employ the new law, adding officials have been looking for a way to establish temporary housing facilities in recent years.

A 2017 report, cited by the Corvallis Gazette Times, estimated between 800 and 1,200 people experience homelessness in Corvallis and Benton County every year.

"This has been a path of discovery for both the county and the church in terms of finding out what rules exist, what opportunities there are and how we can best navigate that path to provide regulated but helpful opportunities for people who otherwise don't have housing," he said.

"The fight came to us."

Situated along a manicured curve of Southwest West Hills Road, First Congregational United Church of Christ is surrounded by cozy, cul-de-sac-filled neighborhoods with decades-old roots.

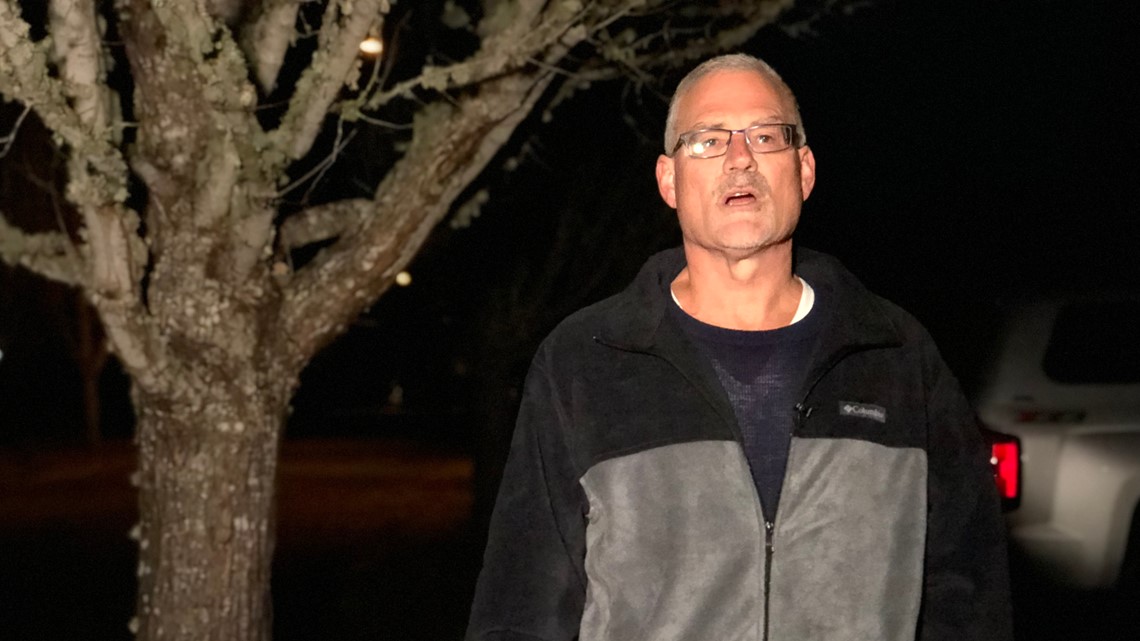

"This neighborhood has been in existence for 25 years. Probably half of it is owned by the original owners," Dan Armstrong said.

The Corvallis attorney told KGW on Thursday night that he and his neighbors were caught completely off guard by the camp's formation, adding they approached church leaders to ask what was going on.

"All of a sudden there was the tents and the tarps and the port-a-potty and the dumpster and the yelling and the fires and the smoke ... you name it," he said. "Bikes coming and going at all hours."

Armstrong said, especially at first, the chaotic moments, particularly yelling and fighting at nighttime, were frequent and frightening.

Undersheriff Greg Ridler couldn’t give specific statistics on how often authorities were called, but he estimated officers were out at the Safe Camp ten times in October.

"Recent activity there has been diminished. It seems we have not responded there as much, but that doesn’t mean it's gone away," Ridler said. "It's just that people are either not calling us because of the difficulty in enforcing a solution there or that the people have not engaged in so much activity that brings police response."

Armstrong isn’t pleased, though.

He said he and his neighbors feel steamrolled by a group of churchgoers who want to solve the housing crisis, adding he read a local "Letter to the Editor" that called him out as being "prejudiced against the homeless."

Of the author, Armstrong said, "He lives three miles away from the problem. He is all in favor of putting the thing across the street from me, in my front yard, and then telling me that I shouldn't complain about it. No. I suggested that if the tables were turned, he would be complaining about it if it was in his front yard."

If the county and church continue to move forward and lay out a permanent path for the camp to stay put, Armstrong said he plans to file a lawsuit. He said it would likely be a "nuisance" lawsuit, declaring the camp as such, meaning HB 2916 wouldn’t have an impact.

"It's easy to talk about being compassionate. It's easy to be self-righteous and smug about providing a homeless camp in somebody's front yard when it's not your front yard, when it's not your kids and your neighbors that are affected by it," he said.

"A chance to survive."

KGW's cameras weren't allowed inside Safe Camp. Walking along the tree line Friday, Reverend Butler explained why.

"These are folks who really aren't afforded any privacy in their lives. Their lives are typically on display for whomever is around, for law enforcement to disrupt their sleep, for neighbors to complain and ask them to move," she said. "So it was really important to us to create a sense of privacy along with the safety we were trying to establish."

That priority is even printed on signs lining the driveway.

They prohibit uninvited photos or visits and request people "respect the privacy of those who are living in our Safe Camp."

Butler invited KGW into the communal kitchen tent, where 51-year-old Jerry Brown had just finished frying carrots for his fellow campmates.

"We try to conduct ourselves clean, sanitary," he said. "I've got a culinary certificate from when I was in Louisville."

The Kentucky native came to Corvallis in 2010, following "a redhead." Brown admits he's on probation after failing to pay child support in his home state.

Work, he said, was never an option. He lives off of disability.

"My knees, my back, one hip and a foot are all to be surgically fixed," he said, showing a small electronic pulse machine that sends shock waves through his system to alleviate the pain.

Brown said Thursday he was one of the many camping in "the Christmas tree farm" when a police officer told them the church was letting people sleep on their property.

He wasted no time.

"I paid somebody to put a tent up to mark my spot," he said, adding the woman he was camping with was hesitant. "I begged her. My tent was broken down. I was living under a tarp for two days, trying to get her to move."

Finally, he said, the two parted ways.

The argument for coming to the church's property, he said, was simple.

"This is legal. We can be here. We at least have a chance to survive. Over there, they're just going to run us [out] and take our stuff," he said.

Brown said he and other campers, one of whom listened during his interview, know neighbors nearby are angry about the camp.

Some have stopped by to voice their frustration.

Others hurl insults from their cars.

"They ride by here screaming, 'Get a job!' OK. I can stand maybe 10 minutes," he said, referring to his injuries.

He said he believes if campers and neighbors could sit down and have a rational conversation, they could find a way to coexist.

"Most people are one paycheck away from being [homeless] themselves," he said.

Meanwhile, Verret told KGW officials hope to have ordinances in place to specifically allow for the camp's existence within the next few months.

Reverend Butler is grateful for the cooperation, and she's hopeful about the future of "Safe Camp."

Seven of the original campers, she said, have already found permanent housing.

"The forest has always housed people," Butler said. "The difference is, now they're seen. And when you bring something into the light, it can either create more fears or alleviate fears, and I think both of those things have been true."