PORTLAND, Oregon — Curtis Rystadt paid the city of Portland more than $7,300 to convene a meeting for a tower that may never rise where he wants it. Twenty-six people came to the Microsoft Teams meeting, from the city, the county and the local transit agency. A few journalists and Rystadt's press agent blinked in. A Bureau of Development Services spokesperson showed up because the journalists were in attendance.

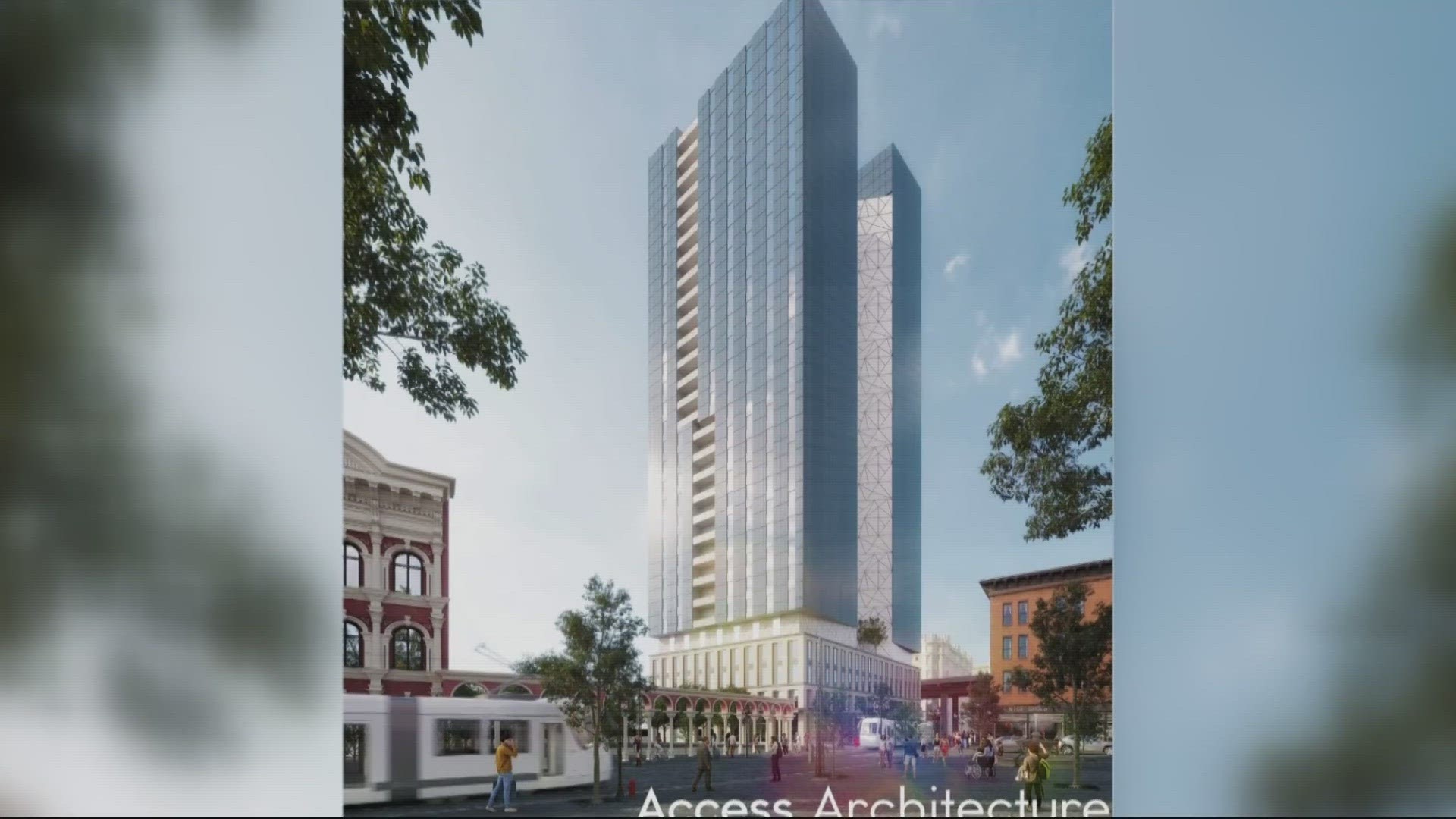

Rystadt's proposed 30-story, 728-unit affordable housing tower, which is not permitted at 108 W. Burnside because of the city's seven-story height limit, was the focus of Thursday's meeting.

Portland needs more low-income homes. The question is whether Rystadt, with little homebuilding experience but civic passion, can go forward with what would be the largest such project in recent memory. He is building his first affordable housing project on Northeast Glisan.

But with his Burnside project, it's not clear if Rystadt is pushing a quixotic development campaign or is a victim of rules and bureaucracy.

Read more from the Portland Business Journal: A 30-story tower proposed in downtown Portland.

Only an hour and a half was scheduled Thursday to talk about the tower, Burnside One. The clock started at 8:30 a.m. BDS’ Matt Wickstrom, with high attendance and many people to get through, set ground rules: “Please no speeches.”

Wickstrom turned to Rystadt, who explained he is a Portlander, born and raised. He had a real estate agent scour Portland for a property along light rail to address the housing crisis. They looked for properties all over, he said. There is nearby property that allows taller construction, he said, but this one fits all the light rail needs. He wants to commit to clean energy and save tenants money on their energy bills.

Foot traffic downtown is very low, and those feet haven’t come back, Rystadt said. Bringing 728 residents to the urban core will help businesses, and it will help the economy. He doubled back on an earlier claim, still unverified, that the city had told him not to limit himself to the 75-foot height limit.

Wickstrom said they were there to talk about the code as it stood today. Brendan Sanchez, the Burnside One architect, acknowledged height had been the biggest point of discussion, but he said he wanted to understand what the other hurdles would be.

What followed were various government representatives laying out site requirements. The Portland Bureau of Transportation stressed the importance of preserving cobblestones by the site, as they are difficult to replace. TriMet would need to work with project officials on any temporary transit stop closures during construction. Rystadt listened.

Read more from the Portland Business Journal: Portland development office rebuffs proposed 30-story housing tower

Tim Heron, a senior city planner, struck a sympathetic tone. He told Rystadt that much of what he was hearing would apply to a 75-foot or less project.

Heron offered encouragement: “You’re coming in really early. That’s great.”

But he remained firm that, at this meeting, he could only talk about city code and height limits as they are today, even as Rystadt tried to rhetorically push left and right, pressing Heron on hypotheticals about going higher, and how his tower needed to go vertical for economies of scale.

“I’m just trying to help, guys,” Rystadt said.

Heron said, “Curtis, you’re preaching to the choir.”

Read more from the Portland Business Journal: Developer pushes 30-story affordable housing tower despite city code restrictions