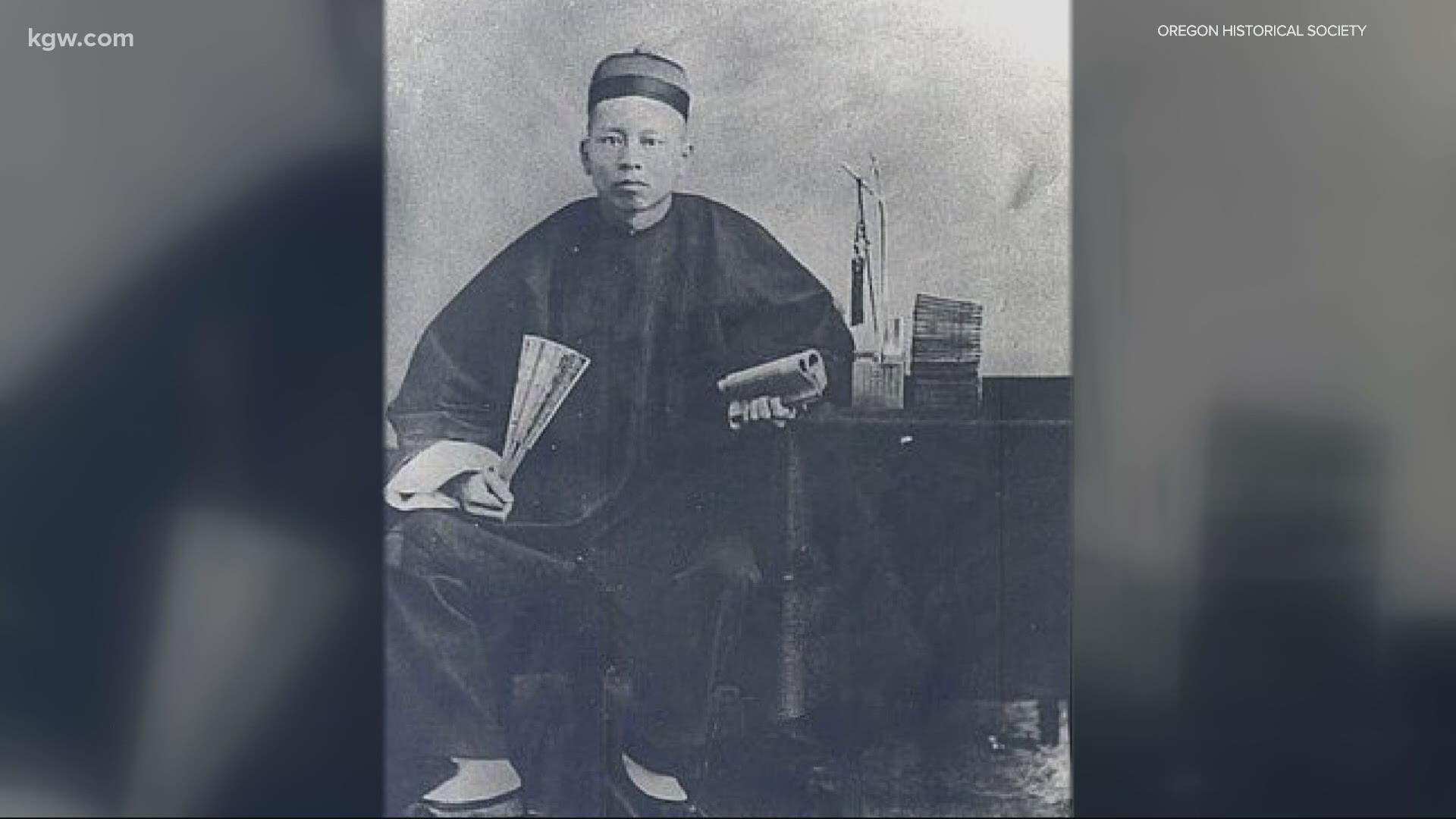

PORTLAND, Ore. — The Chinese community has deep roots on the West Coast and in Portland. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 8% of people in Portland identify as Asian.

“Very few people, even Chinese-American, know that just 100 years ago, Portland had the second largest Chinese population next to San Francisco. Every 10 people in Portland, one was Chinese,” said Hongcheng Zhao, President of the Oregon Chinese Coalition.

That was around 1890. But it was in the mid-1850s when Chinese immigrants started coming to Oregon.

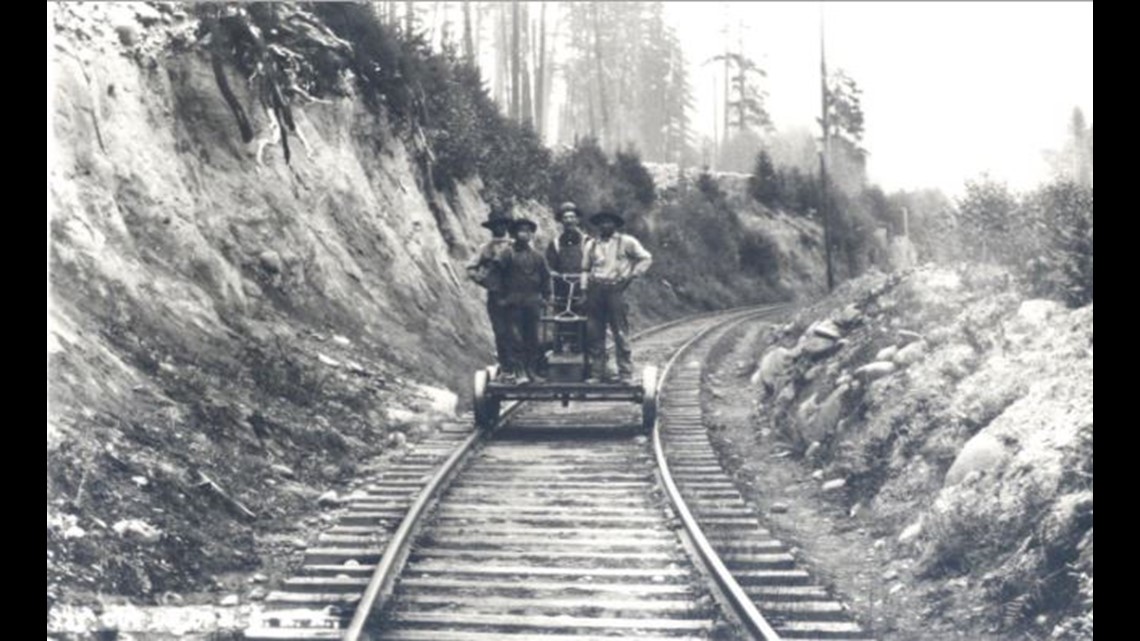

“The reason Portland used to have that many Chinese Americans is mainly related to the Transcontinental Railroad construction,” said Zhao.

He said about 20,000 Chinese immigrants did most of the backbreaking work on the west side of the Transcontinental Railroad with about 90% of the workers being Chinese.

Chinese laborers worked in canneries on the Oregon Coast as well. They also did laundry, cooking, and were street vendors.

“We’re doing all these jobs right? For cheap,” said Neil Lee, President of the Oregon Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association.

But with all that hard work also came discrimination.

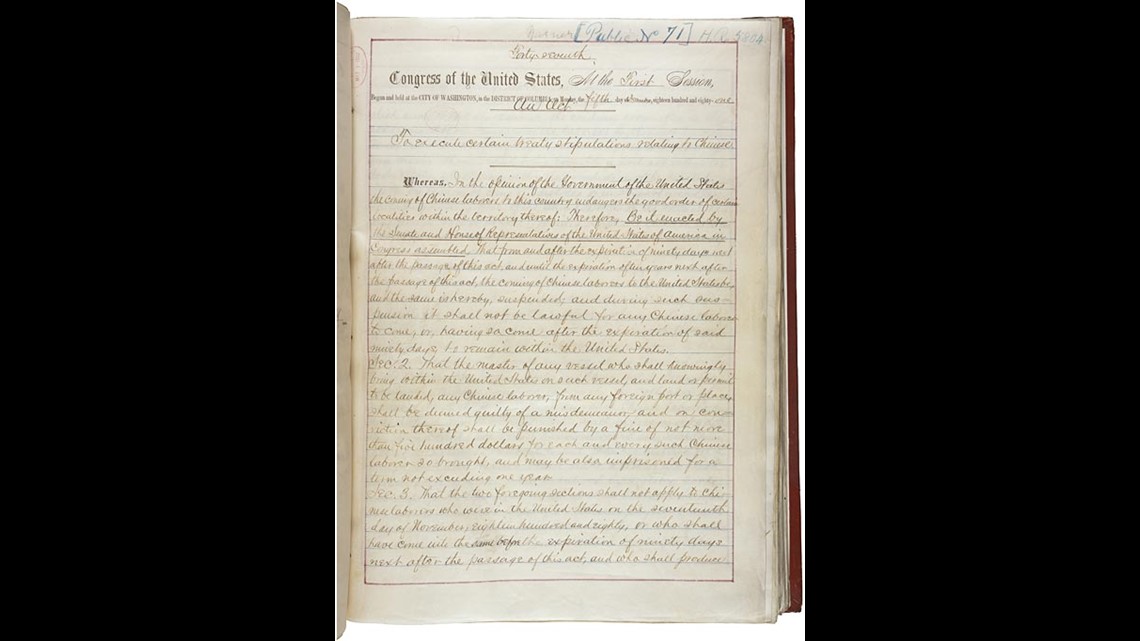

“There’s this hate, like ‘oh they’re taking our jobs away,’ and that’s what the Exclusion Act was based upon,” Lee said.

The Chinese Exclusion Act, was passed by Congress in 1882 and was not repealed until 1943. It banned Chinese laborers and was the first in American history to put broad immigration restrictions on an entire group of people. The restriction included the wives of any workers who were already in the states.

The 1910 Oregon Census shows the ratio of men to women was about 22 to 1, though Zhao said he thinks it may have been more like 29 to 1.

“Most of the Chinese laborers here never got married and died lonely here,” he said.

There were other incidents too. The Chinese massacre at Deep Creek in Wallowa County and expulsion of Chinese from Oregon City are just a couple instances of violence and discrimination.

“Back then the white government didn’t really care much for us. So, we had to take care of our own,” Lee said.

He said the Chinese community even had its own courts.

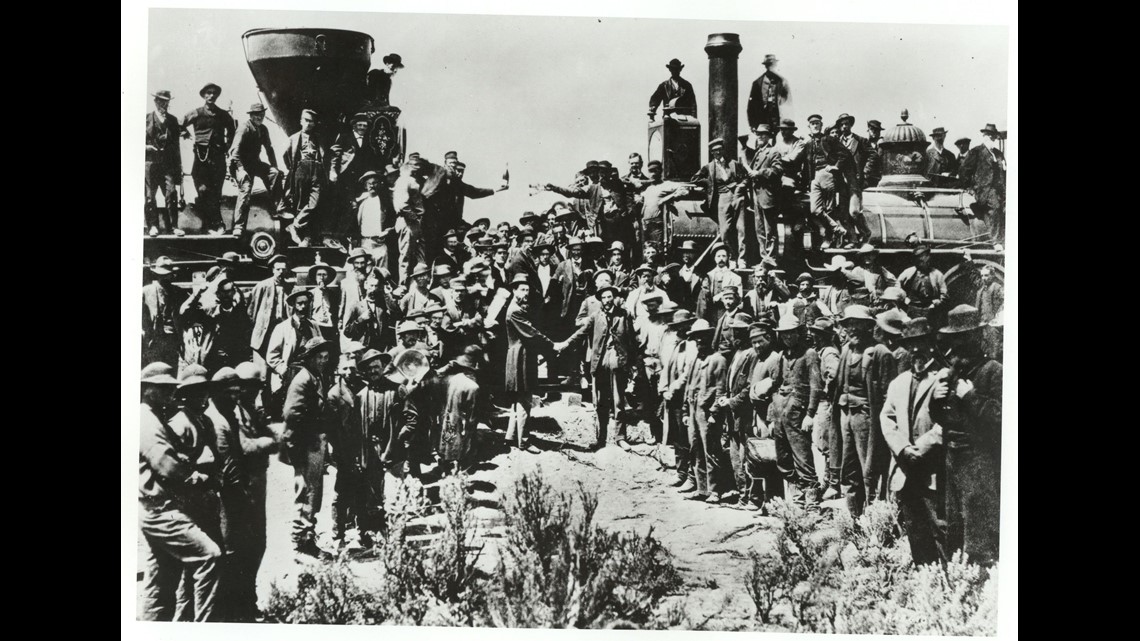

All the while, the Chinese remained largely unrecognized for helping complete the Transcontinental Railroad. A photo documenting the momentous occasion, shows no Chinese laborers.

“You won’t see one Chinese in that picture, and that is by intent,” said Gloria Lee, a board member of the Chinese American Citizens Alliance.

So, the Chinese became their own isolated community.

“Chinese have chosen to stay less visible because if you’re less visible, you’re safer,” Gloria Lee said.

Over time, many Chinese people moved out of the once vibrant Chinatown in Portland.

“I think the consensus is, the over concentration of social services in Chinatown is the biggest reason,” said Zhao.

Now, he said a lot of Chinese people have moved to the outskirts, to places like SE 82nd Avenue and the Bethany area, which is closer to big employers like Intel and Nike. The deep pain associated with historical mistreatment has, for some, continued into more recent years.

“After you’ve been excluded for 63 years, you might be a little afraid of what’s coming around the corner,” Gloria Lee said.

She said historically, Chinese-American people don’t tend to pay much attention to elections and voting, with voter registration for Chinese people, being one of the lowest among other ethnic groups.

The Center for American Progress, a policy research organization, found that in 2016 more than 64% of white Americans turned out to vote, compared to 49% of Asian Americans.

But things seem to be changing with the younger Chinese generation.

Sunset High School junior, Jiaqi Zhang just turned 15 years old this year. She said growing up in Beaverton, she’s developed more of a connection with her larger, more diverse community. But that’s also presented other issues.

“Instead of feeling disconnected from other cultures, I feel more disconnected from my own,” said Zhang.

Zhang is trying her best to connect with her Chinese roots and trying to change perceptions while she’s at it.

“We’ve just really been trying to make ourselves known as a community who is helpful and not super secluded,” Zhang said.

A more recent hurdle, though, has been the COVID-19 pandemic. Some, namely President Donald Trump, have labeled the coronavirus the “China virus.” Gloria Lee said she’s noticed some people look at her differently.

“I really am conscious of having a Chinese face,” she said.

In the beginning of the pandemic, Chinese restaurants in particular suffered. People were misinformed, assuming there was a connection to COVID-19. There were even reports of attacks against Asians.

“Some people from the community did receive some nasty messages with full of hatred,” said Zhao.

Lee said he heard Chinese people being told to "go back to China."

“It’s really horrible, really horrible,” he said.

But even in the midst of that, the Chinese community is giving back, working with different groups within the Chinese community and outside of it, while also continuing to publicly showcase its vibrant culture.

“We have made a great efforts and people started to see the changes. We want to continue with the momentum,” said Zhao.

Part of what’s also made it difficult to connect those in the Chinese community, is that there are different groups under the larger Chinese umbrella. There are those who have come from mainland China and were educated there, others who came to the U.S. for an education, and still others who are American-born Chinese.

Each of these groups may feel differently on certain subjects. But Gloria Lee said what is true across the board for all Chinese people, is a respect for elders, love of food and caring for community.