EUGENE, Ore. — Oregon State University researchers have made it easier to learn about the gray whales who often visit the state's coastline — by their names, features, reputations and habits.

The Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Laboratory at OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute has developed a website that allows visitors to meet some of the whales the researchers have identified over the years. The website aims to teach about the animals, the stressors humans put on whale populations and how those stressors can be reduced.

“We wanted to share with Oregonians, and the public in general, the stories of these whales because they are residents of Oregon like us, and they have personalities and stories to tell,” Leigh Torres, principal investigator of the Geospatial Ecology of Marine Megafauna Laboratory at OSU’s Marine Mammal Institute, said. “These whales have interesting lives that we’ve learned a lot about over the years through our research.”

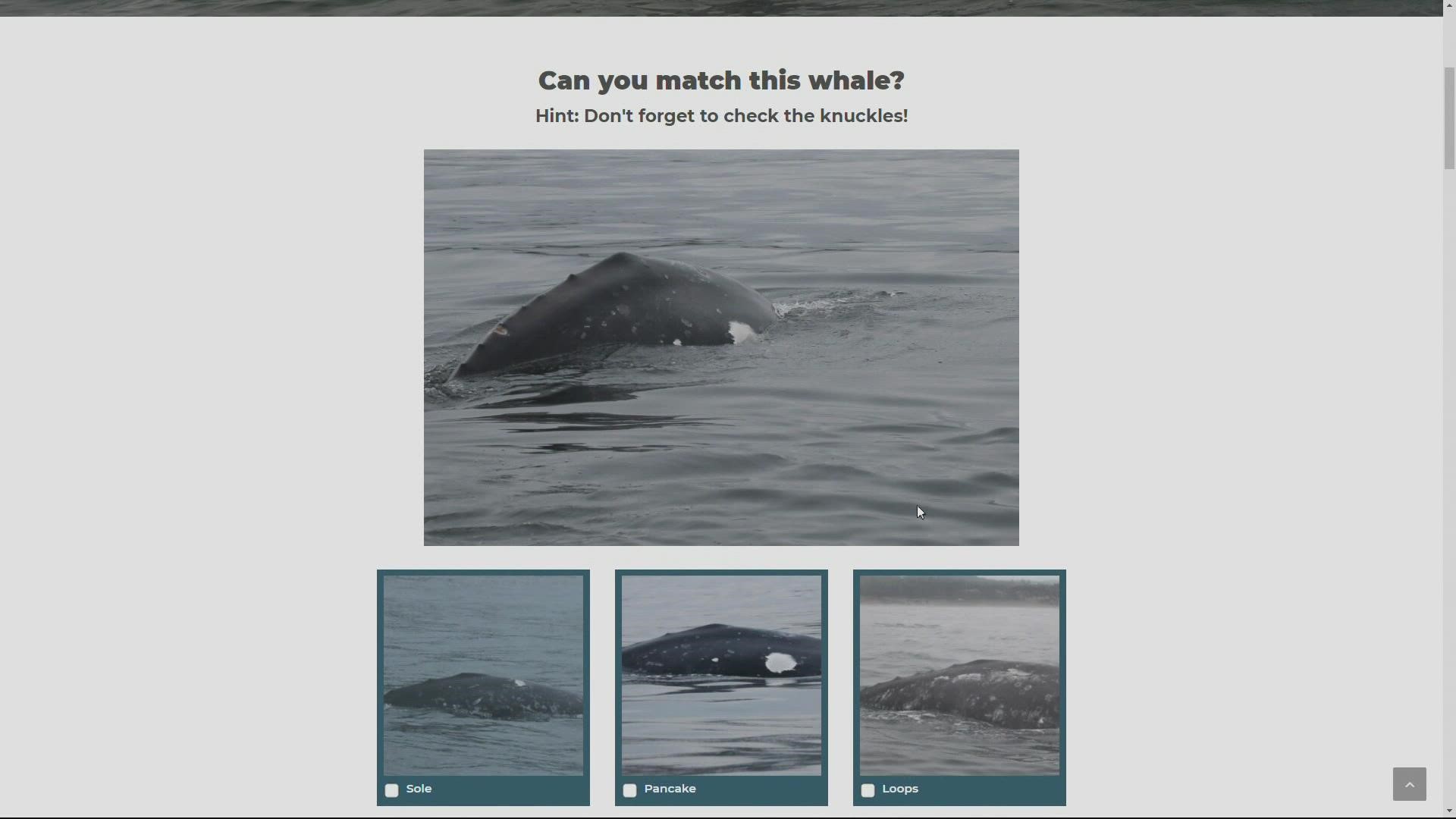

At individuwhale.com, visitors can learn about gray whales:

- Orange Knuckles is a mature male gray whale first spotted in 1999 "who likes the ladies."

- Sole is "a homebody who knows what she likes and sticks with it."

- Equal's "encounter with a boat propeller provided researchers insight into gray whales' stress responses."

Winter and summer visitors

Most gray whales in the eastern north Pacific Ocean population cruise along Oregon’s coast as they migrate south in December and January to breeding grounds in Mexico. The come back north in March to feeding grounds in the Bering and Chukchi seas between Alaska and Russia, where they spend the summer.

Torres and her team study a distinct population of gray whales known as the Pacific Coast Feeding Group, which spends the summer months feeding in the coastal waters of Oregon, as well as waters in northern California, Washington and southern Canada.

Torres and her research team have been observing and conducting annual “health check-ups” on this population since 2016, according to a news release. When they spot a defecating whale from a boat or via a drone, they follow in the animal’s wake and use nets to capture samples that can be used to monitor whales' reproduction and stress.

The drones are also used to capture images of the whales, allowing researchers to monitor the animals’ body condition and behavior.

“We know their age and sex, their body condition and we can also track some of their different experiences, such as injuries or reproduction,” Torres said in the news release.

Meet some of the whales

Torres and her team have catalogued about 190 whales and given each a name and an identification number. Some whales are so well known they can be recognized instantly.

Eight of the well-known whales currently are featured on IndividuWhale.

Scarlett, a gray whale also sometimes known as Scarback, is one featured whale from the Pacific Coast Feeding Group frequently seen in the Depoe Bay and Newport areas.

“We’ve seen her every year that we’ve gone out on the water,” doctoral student Lisa Hildebrand said in the news release. “She’s a resilient whale who recovered from this huge wound on her back and then was able to successfully reproduce.”

Another featured whale, Roller Skate, was first identified as a calf in 2015. In 2019, she was spotted with fishing line entangled around her fluke.

In 2020, the researchers documented her again in the same area.

“She survived a very gnarly embedded wound, and part of her fluke was effectively amputated,” Hildebrand said. “She dives differently now than she did before the injury.”

In the news release, Torres said the website aims to educate the public about human-caused threats to gray whales, including propeller injuries and entanglement in fishing gear.

Gray whales also face changes in the availability of their prey due to changing ocean conditions that affect the health of kelp forests the whales depend on for food.

“We want people to understand the connection between their behavior and these individual whales,” Torres said in the news release. “If everyone changes one behavior, like slowing down while boating near the reefs where gray whales feed, reducing use of plastics that pollute the ocean and removing recreational crabbing gear promptly so animals don’t get tangled in it, these are all things that can make a huge difference.”

The IndividuWhale project was funded in part by Oregon Sea Grant and the Marine Mammal Institute. Erik Urdahl, a website developer, donated services to build the site.