'An ideal opportunity to go unnoticed': Lawsuit, litter & fires point spotlight at homeless on beaches

The state has installed several 'no camping' signs along a stretch of Swan Island, after getting complaints from the Port of Portland and Daimler.

The lawsuit

Two years ago on a sunny Tuesday afternoon, a Portland couple decided to use their day off to visit the city’s newest public beach.

It was a big attraction at the time.

The Human Access Project had lobbied for it. The Mayor had endorsed it. Newspapers and TV stations, including this one, covered its highly anticipated opening.

Andrew and Kelly Corrado were excited to explore the sandy stretch along the Willamette’s western bank under the Marquam Bridge, dubbed Poet’s Beach, for themselves.

Given the crowds, they set up chairs along the shore, just south of the beach.

By that evening, they were in the hospital.

“It could have been anybody,” said Andrew Corrado last week. “We weren’t targeted.”

Police said a man and woman camping near where the Corrados had placed their chairs had become angry the couple’s dog wasn’t on a leash.

The man, later identified as Jonathan Rance, attacked them with a baton, striking Andrew in the shoulder and Kelly in the head.

Recounting the ordeal earlier this month, Andrew Corrado remembered watching Rance pick Kelly up by the shoulders and throw her “about ten feet onto the rocks” before beating her with the baton.

Kelly Corrado said she felt "like I was the only person in the world. There was nobody there. And that he was going to kill me. That I was going to die."

Two years later, the Corrados sat down with KGW 24 hours after filing a federal lawsuit against the city of Portland for $500,000 each.

In it they allege that, in the days leading up to the attack, the Portland Police Bureau had been contacted between three and five times about Rance, with reports of assaults, threats and disruptive behavior but that they had failed to arrest him or remove him from the beach.

Corrado even remembered a police officer approaching them earlier that day, advising them they’d be “safer” if they sat on Poet’s Beach, further away from Rance’s tent.

“I kind of thought that was an odd comment… We’re just sitting on the rocks by the river,” he recalled. “But after the fact, here now at 5:30 where I’m following the ambulance going to Emanuel Hospital with her in the ambulance, I’m sitting there going ‘Well, that was a really bizarre comment. If you felt there was danger at that moment, and you’re advising us to go to a different part of the beach… Why has this family been camping there this long?’”

In light of pending litigation, the Portland Police Bureau declined to comment on the attack or what led up to it.

Portland Parks and Recreation, who maintains Poet’s Beach, also declined to comment on the lawsuit.

State posts "no camping" signs along another beach

In the month leading up to the Corrados filing their lawsuit, Oregon’s Department of State Lands, or Oregon DSL, was tallying up a list of problems on a separate beach along the Willamette River’s eastern banks, roughly five miles north of Poet’s Beach.

In a news release, sent out last week, officials said they’d documented instances of littering and dumping, reckless burning and open fires and damage to property along Swan Island’s Lindbergh’s Beach.

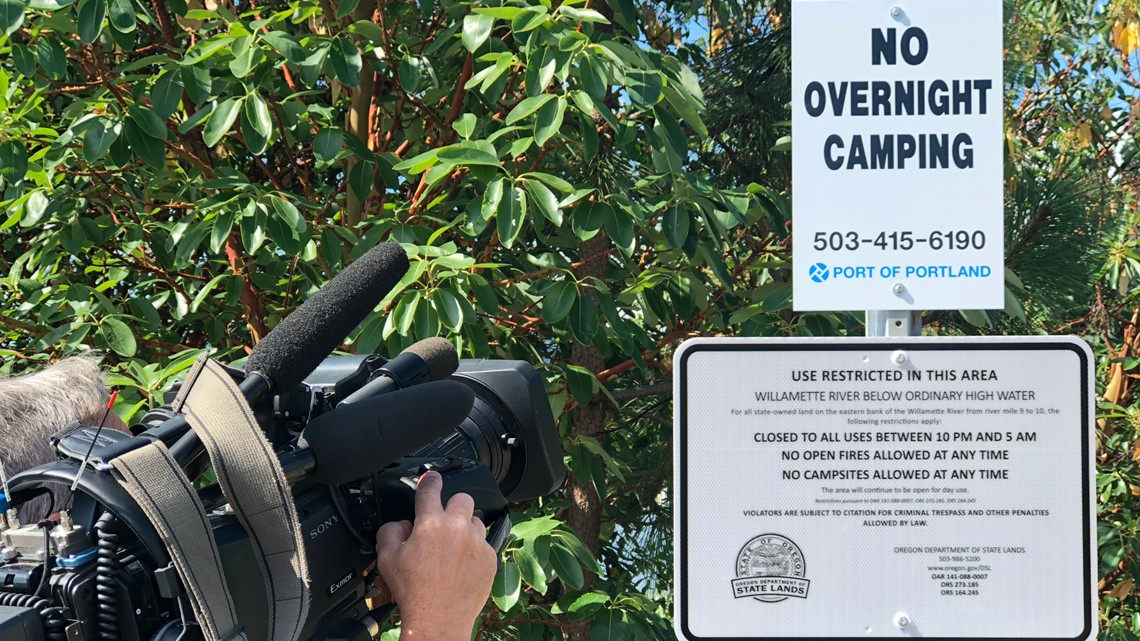

Last week, new signs went up along the walkway leading to the shore:

“NO OVERNIGHT CAMPING”, “CLOSED TO ALL USES BETWEEN 10 PM AND 5 AM”, “NO OPEN FIRES ALLOWED AT ANY TIME” and “NO CAMPSITES ALLOWED AT ANY TIME” are among the listed warnings.

Both the Port of Portland, who owns property next to the beach, and the Oregon DSL have their logos emblazoned on the signs.

Staff with the Oregon DSL said Wednesday the issues came to light in June, when the Port of Portland and their tenant Daimler Trucks North America sent a letter to the state, complaining about the issues along the beach.

The letter is included here on page 45 of this meeting packet for the State Land Board.

Communications manager Ken Armstrong said it was the first Oregon DSL officials had heard of any problems or any campers.

“You know, when you’ve got an urban environment, like we do in Portland, and it’s forested with beaches, it’s kind of an ideal opportunity for things to go unnoticed,” said Armstrong. “People that want to go out and recreate with their kids or bring their dogs or what have you… that’s just not a good interface.”

Friday, KGW went to Lindbergh’s Beach to see what that interface actually entailed and found close to a dozen people live in tents, tarps and, in one case, a log cabin.

The man who built that is a military veteran with PTSD, said Donald Ferris.

He himself had been camping on the beach for two and a half months.

“Some of them have been here a couple years,” he said. “Out here it’s very mellow. You’ve got the waves. You’ve got the noises.”

Ferris, like other campers present Friday morning, were aware of the signs.

He admitted there have been some problems.

“This guy here just left, and he left a whole bunch of junk. We’re picking that up,” he said, pointing to a pile of belongings about 30 feet back from the water. “And then there was a fire down there.”

Ferris said a tent had caught fire earlier this summer, but he wasn’t sure how. The camper inside wasn’t injured he said.

He maintains, though, campers work hard to keep the beach clean.

“But if you go to other camps that are just piled with stuff, you know you see bags of garbage and all that… You won’t see that here,” he said.

Ferris said he believes the complaints carried more weight because people tend to judge homeless campers as being dangerous.

“They automatically make that stereotype of ‘Oh they’re homeless? Oh God,” he said. “I have a pitbull puppy. His name’s Buddy. Most loveable dog you’ll ever meet. Loves every dog, every person. But you walk down the street and people see them, they’re like ‘Oh God!’ They back away.”

The Port of Portland released the following statement:

The Port owns the property in question in the Swan Island Industrial District up to the ordinary high water line. We’ve seen unwanted activities such as littering and dumping, camping and damage to our property. We can make efforts to eliminate these activities from our property, however to effect change in the area, we need the partnership of the Department of State Lands since indistinct property boundaries are challenging.

We appreciate the efforts DSL has taken with regard to notifying the public and posting signs about prohibited activities. We are concerned about the accumulation of garbage and human waste and its impact to water quality as well as the public’s ability to enjoy the river. Working together, we hope to be able to enforce property rights and ensure that the beach and Willamette Greenway trail are available for everyone’s use and enjoyment.

What's next?

These days, Poet’s Beach is peppered with teenagers in swimsuits, people walking their dogs and, according to Portland Parks & Recreation spokesman Mark Ross, park rangers who visit daily.

“Park Rangers are not law enforcement officers, but rather goodwill “ambassadors” in parks, who have direct lines to maintenance staff and social service providers, and partner with other City staff as needed,” said Ross via email. “When Rangers contact people who are experiencing homelessness, their primary goal is to connect them with social services so they can get needed help. Rangers have training in approaching people experiencing mental health challenges, and prioritize de-escalation.”

Ross added Portland Park Rangers increased their presence at Poet's Beach after the Corrados were assaulted, and they've maintained that presence during daily patrols.

Ross referred KGW to city code, listing prohibited activities on land maintained by the Bureau, which includes erecting structures of any kind, such as tents.

The Rangers hotline, he noted, is 503-823-1637.

Those restrictions were in place when the Corrados were attacked.

A lifeguard and a ranger, stationed at Poet’s Beach, were the ones who called 9-1-1.

Andrew Corrado remembers Rance scoffing at them.

“They’ll never find me. I’m just going to disappear, up under the road, disappear. And I’m going to watch what car you get into. I’m going to follow you home,” he remembered Rance saying. “And oh by the way, I’ve got a shotgun in my tent.”

Rance fled the scene but never made good on that threat.

He was arrested by police days later, and last year he pleaded guilty to second degree assault and two counts of unlawful use of a weapon.

He’s currently serving five years in prison.

The Corrados’ lawsuit is pending.

“Unfortunately there’s a lot of panic and anxiety that I have that I never had before, and I’ve had to learn how to trust people, and that’s really tough because I shouldn’t have to question every person I come in contact with,” said Kelly Corrado of the aftermath. “It’s terrible. It’s an awful thing to live with.”

On Swan Island, Ferris said the signs listing prohibited activities are the only indication that anything will change.

“We’re waiting to get posted,” he said of official notices ordering camps be cleared. “They’re basically waiting to find out when they’re going to post them and say ‘You gotta go.’”

He also said no one from the state or local law enforcement agencies has talked to campers about the new rules.

Armstrong told KGW Wednesday there’s no set timeline for when that might happen.

He added the Department of State Lands is hoping to work with Portland Police and the Multnomah County Sheriff’s Office.

“Six months from now, is that going to look exactly the same as what we’re approaching right now? I’m not sure,” he said. “I think there’s a lot of resources out there that are going to inform how we do this in the best possible way… But I think it is a societal problem right now that everyone needs to pitch in and find ways to help. One just can’t sort of stay on the sidelines and say ‘That’s not my problem.’”

Ferris, who spends his days working on his broken down boat along the shore, doesn’t expect anyone will leave on their own accord.

“Because then they figure out a whole new spot to live,” he said “And then what? They’re put back out to where next week they’re going to get swept again and have to move. The week after that, they’re going to get it again.”