SALEM, Ore. — A workgroup of Oregon's top judicial, health, legislative and community leaders is recommending dozens of changes to the state's mental health and civil commitment laws, following an extensive 2-year review. However, the group couldn't agree on lowering civil commitment standards or creating a tiered system for civil commitment involving both inpatient and outpatient options.

The "Commitment to Change" workgroup was formed by the Oregon Judicial Department in 2022 to study Oregon's mental and behavioral health systems, namely civil commitment — the involuntary detention and treatment of a person whose mental illness makes them a danger to themselves or others.

"Oregon's civil commitment system is failing to protect some of the state's most vulnerable residents," said the CTC co-chairs Judge Nan Waller and Judge Matthew Donohue in the report's introductory letter.

KGW investigations has explored how Oregon's current civil commitment system has effectively criminalized severe mental illness, waiting for an individual to commit a crime before mandating treatment and care. Oregon courts receive about 8,000 notices of severe mental illness each year. Only about 6% of those notices reach the legal threshold for civil commitment.

"We are concerned about the roughly 7,500 individuals experiencing serious mental health challenges [each year] who may not receive needed services, supports and treatment," Waller and Donohue said. "This report reflects hundreds of hours of thought and discussions about Oregon's civil commitment system by the individuals who make the rules, carry out the work, and experience it as an involuntary participant or advocate of participants."

The CTC workgroup reviewed hundreds of "reform ideas" to create a list of recommendations for lawmakers ahead of Oregon's 2025 legislative session.

The group's members unanimously agreed on 51 recommendations, including:

- Oregon should ensure that publicly-funded residential behavioral health care facilities are available and accessible statewide

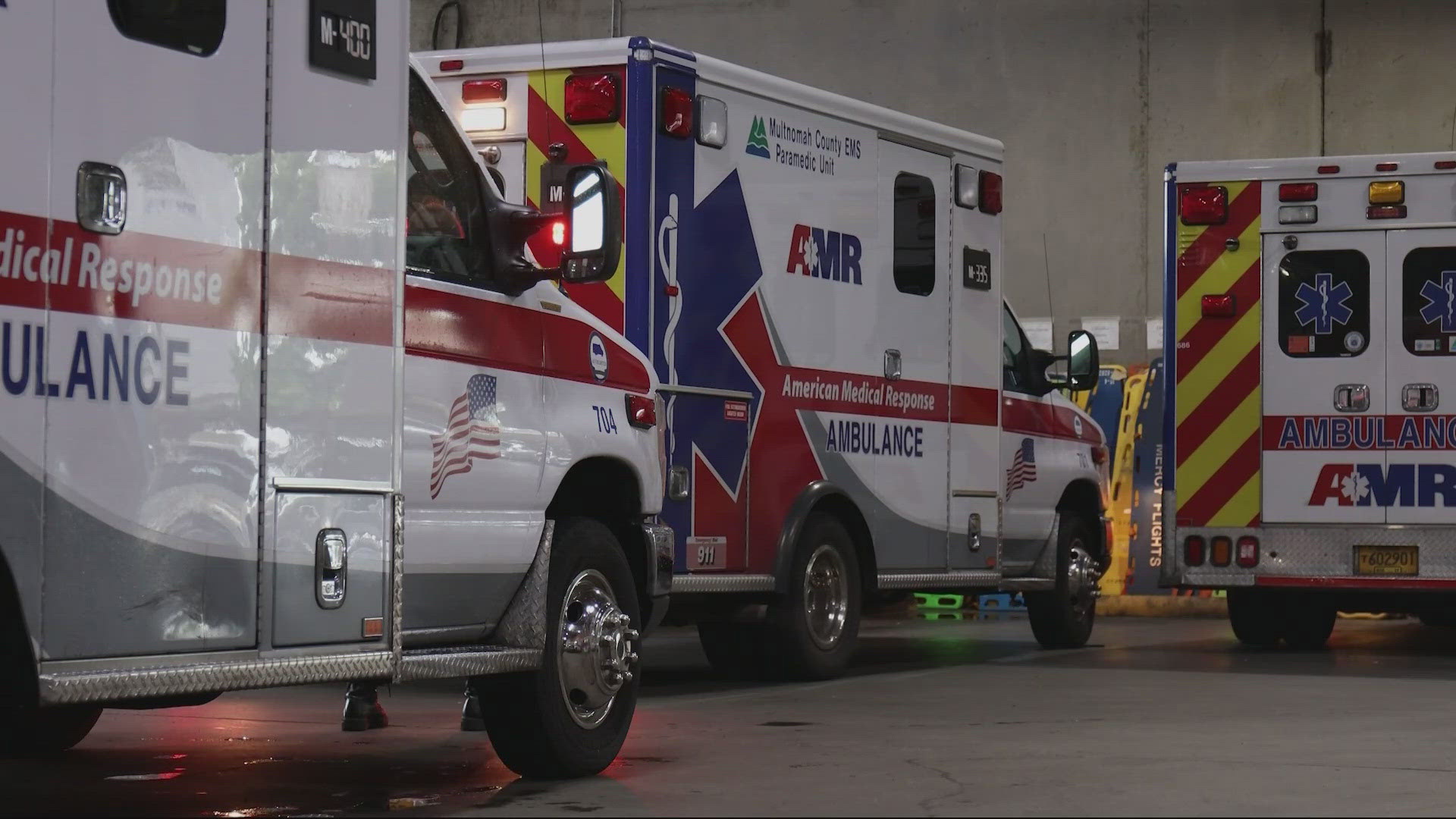

- Oregon should develop and fund alternatives to emergency rooms and jails for individuals in crisis, such as local stabilization centers, urgent walk-in clinics, street outreach and recovery centers

- Amend Oregon law and provide funding to make sure transitional services are offered to someone who completes civil commitment diversion treatment

- Expand the number of mental health examiners for civil commitment cases, adding a centralized database

- Establish and fund statewide intensive care case management services and local treatment programs for anyone following a Notice of Mental Illness, whether they're committed or not

- Require the Oregon Judicial Department to anonymously track people who are certified for continuing commitment more than once

- Improve communication between jails and the Oregon State Hospital related to civil commitment discharges

- Expand training to behavioral health providers, counties, judges, district attorneys and public defenders on the purpose, legal requirements, and process of civil commitment

Many other ideas failed to make the "unanimous recommendation" cut, including a proposal to lower Oregon's legal threshold for civil commitment that was listed as a "Top 5" priority by six of the 15 groups and supported by six others.

Jerri Clark, a family advocate and founder of Mothers of the Mentally Ill, told KGW that the group's "biggest miss" was its failure to unanimously redefine "dangerousness" and lower the bar for civil commitment so that more than 6% of people initially recommended for involuntary treatment can receive it.

"The law doesn't define dangerousness, leaving interpretation up to the courts and enabling a standard of imminence that requires, instead of prevents, tragedy," Clark said, referring to Oregon's priority of criminal admissions over civil admissions.

In a "Looking Ahead" section, the report's writers acknowledged that a lack of consensus among all stakeholders has prevented civil commitment reforms in the past, as lawmakers prioritize legislation with broad agreement.

Clark said lawmakers could still decide to look beyond the list of unanimous recommendations and introduce other proposed reforms to the civil commitment process, including redefining civil commitment standards.

"NAMI Oregon is leading work to inspire lawmakers to work on that, which is great, but it’s a disappointment that the CTC couldn’t reach consensus on an aspect of the commitment system that is so integral," Clark said.

Clark added that the CTC workgroup's process was valuable and she's proud of how they produced an in-depth look at Oregon's complex civil commitment process, its history, and the legal and medical complexities.

The report includes a section that lists the Top 5 priorities for each involved organization and their representatives.

It ends with a call for lawmakers to "revisit the hundreds of reforms proposed in greater depth and with fresh perspectives" and to "consider the positions of nearly two dozen different stakeholder groups presented in the report, survey results, and workgroup minutes as a starting place to set priorities and move promising ideas forward."