PORTLAND, Ore. — The knocking wouldn’t stop. Someone was pounding on the front door. It was early, just before 6 a.m. Elizabeth Andrews crawled out of bed.

The 12-year-old figured her dad forgot something. He’d just left for work.

As she approached the entryway of the family’s apartment in Vancouver, Wash., a bleary-eyed Elizabeth noticed her father wasn’t at the door.

Instead, a pair of strangers stood before her in the pre-dawn darkness.

“We need your mom,” said one of the officers with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Elizabeth’s mother, Wilitha Andrews Jarju, who is hearing impaired, didn’t hear the knocking. But soon, she’d wake up to a nightmare.

The Raid

On February 23, 2018, a team of ICE officers arrested Gibril Jarju, also known as Gabe, as he left his Vancouver apartment for work.

“I’m like, ‘Wait a minute. Are you guys taking my husband?’” Andrews Jarju recalled. “And they said, ‘Yes, we have him in the van.’”

Within weeks of his arrest, the 46-year-old father and husband was on an airplane to his native Republic of The Gambia, a small country in West Africa. He’d been deported.

Jarju’s case highlights the United States’ complex and often confusing immigration system.

His family doesn’t understand why a man with no criminal history, married to a U.S. citizen was forced to leave his two young daughters and a country he called home.

“Why did they do that?” asked Jarju’s oldest daughter, Elizabeth.

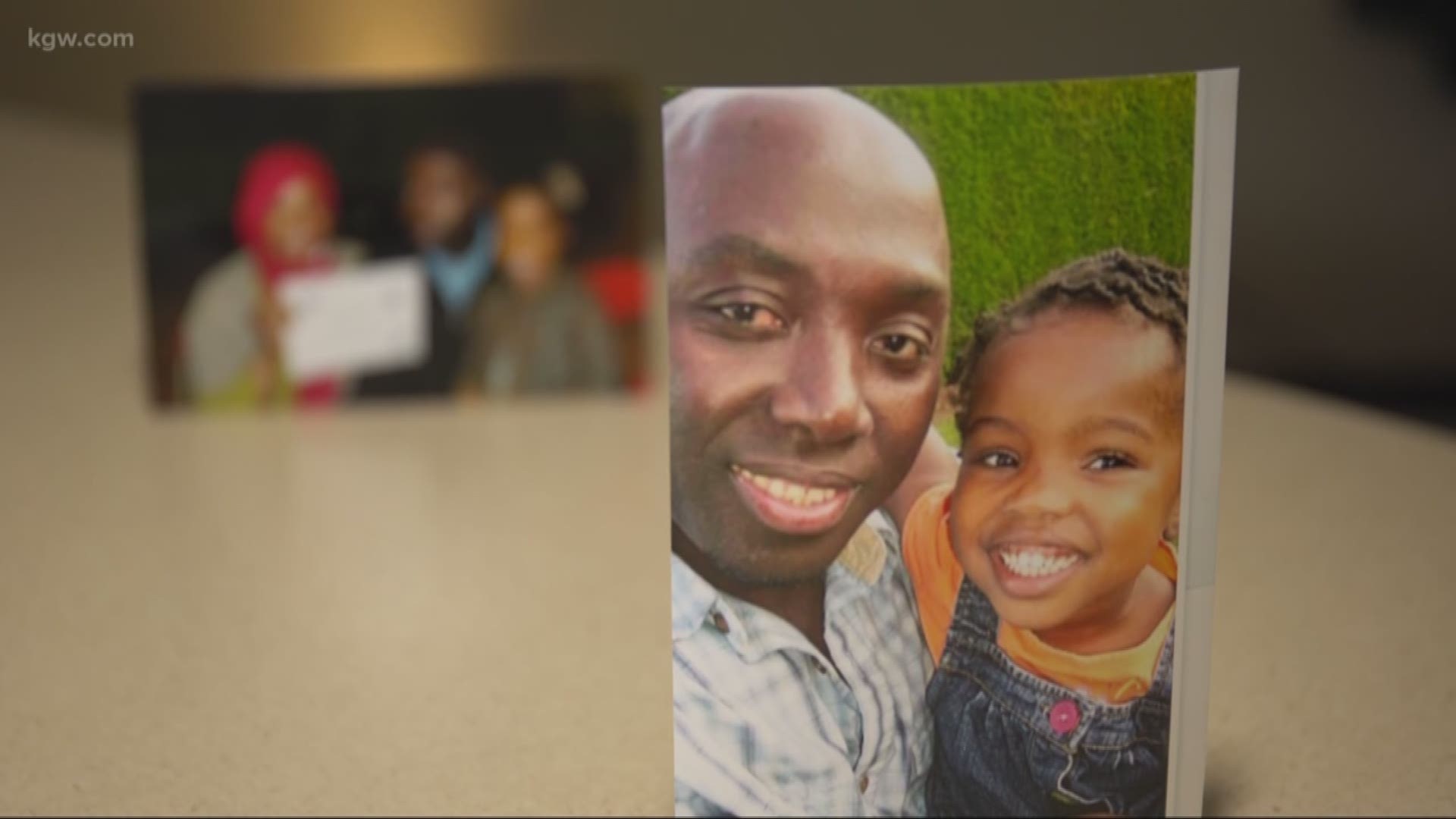

A husband and father

Before his deportation, Gabril Jarju loved spending time with his little girls. He adored them.

“I’ll ask him if he wants to play dolls with me, he’ll say, ‘OK, sure,’” said Elizabeth.

Jarju would often join his daughters for a tea party. They’d use real tea to make the play date more special.

His youngest daughter Aisha, who has an intellectual disability, enjoyed the special attention.

They’d spend hours together at the family’s apartment watching children’s movies, including favorites like Tinker Bell and Barbie.

“Sometimes he pretends to be sleeping, but I know he’s watching the movie,” said Elizabeth.

Jarju worked at ControlTek, an electronics manufacturing company in Vancouver. When he first started there, an introductory message sent to co-workers shared details about the new employee’s background and interests.

“His favorite foods are African foods, fried rice and KFC. His favorite movie is “Coming to America” with Eddie Murphy and Arsenio Hall,” the company newsletter read. It also described Jarju’s passion for soccer.

Jarju worked a second job as a security guard with Metro Watch. He hoped to someday wear a police uniform in America, like he did in his native country.

Coming to America

According to his family, Jarju had worked as a police officer in The Gambia. He fled in May 2001 as the small African nation faced increased political unrest.

Jarju was admitted to the U.S. as a tourist or nonimmigrant visitor, but overstayed his visa.

In March 2007, an immigration judge granted him voluntary departure. The process would allow Jarju to return to his home country by mid-July, and in return, ICE wouldn’t put an order for removal on his record.

Jarju didn’t leave. Instead, he stayed in the U.S.

According to his family, Jarju filed for political asylum. A judge denied the request. Typically, once a person is found not eligible for asylum, the case is sent to the immigration courts and the deportation process begins.

In April 2011, ICE arrested Jarju because he was an ICE fugitive. At the time, Jarju avoided deportation because The Gambia wasn’t issuing travel documents for citizens returning to the country. He was released.

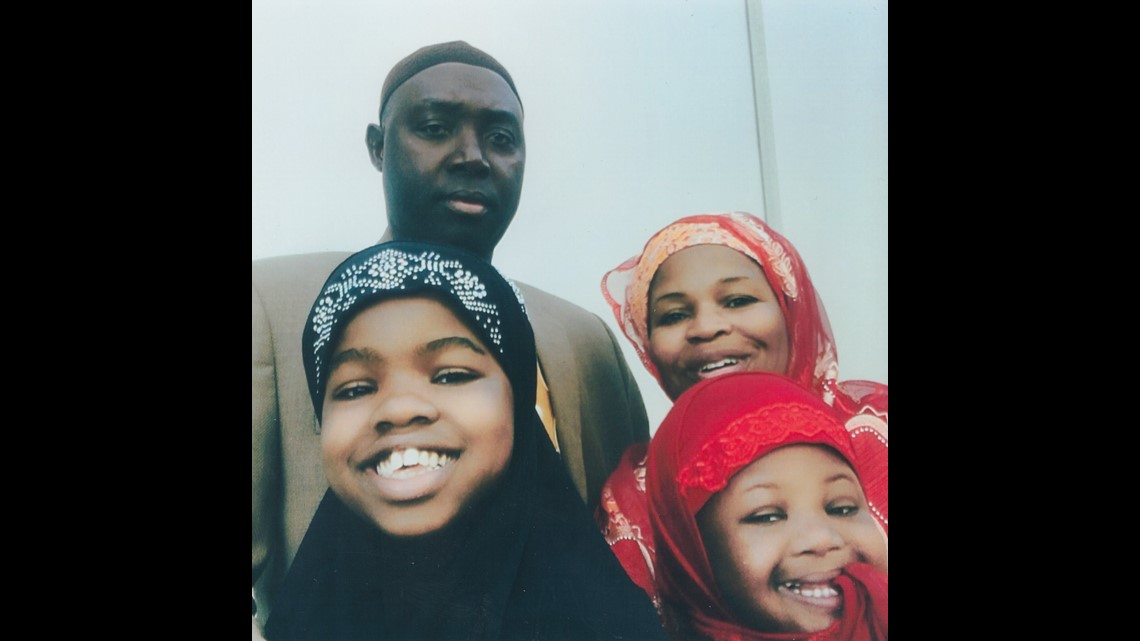

Despite his immigration issues, Jarju was building a new family in the U.S.

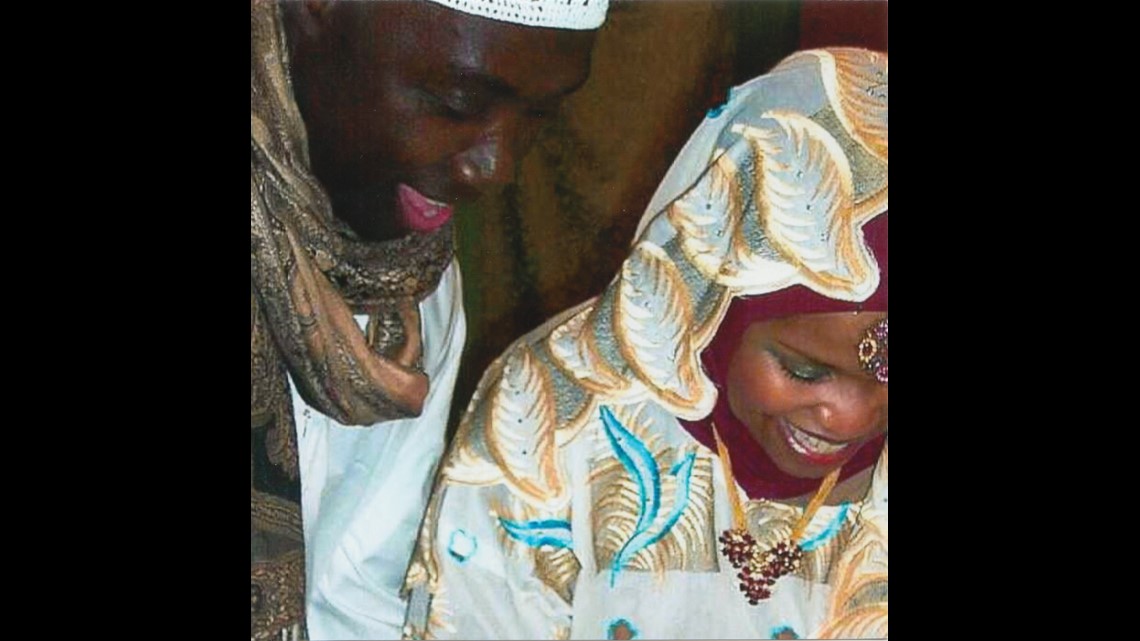

Jarju met his future wife, Wilitha Andrews, after holding the door open for her at a Salvation Army store in Vancouver.

“We hit it off right away,” said Andrews Jarju, who is a U.S. citizen. She was born in Chicago and grew up in the Vancouver area.

Andrews Jarju laughingly said that her husband was tall and clumsy. He found a joke in everything.

“He’d always show me the good side of things,” she said.

Meanwhile, Jarju and his lawyer tried to cut a path toward citizenship. In February 2017, his attorney requested that ICE join in a motion to reopen the case. Details of that request were not available. It was declined in December 2017.

Records provided by the family show Jarju checked in with federal officers on a regular basis starting in October 2011. The handwritten log shows Jarju last checked in with ICE on September 13, 2017. His next reporting date was scheduled for March 14, 2018 at the ICE office in Southwest Portland. He never made it.

On February 23, a team of ICE officers arrested Jarju outside of his Vancouver apartment. He was sent to the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Wash.

Over the next few weeks, Jarju would be transferred to a different ICE detention center in Texas. His family scrambled to find Jarju an immigration lawyer who could help intervene, but the challenge proved insurmountable. His family didn’t have the contacts or the money to fight the government.

On March 9, 2018, Jarju arrived in his home country of The Gambia, according to ICE.

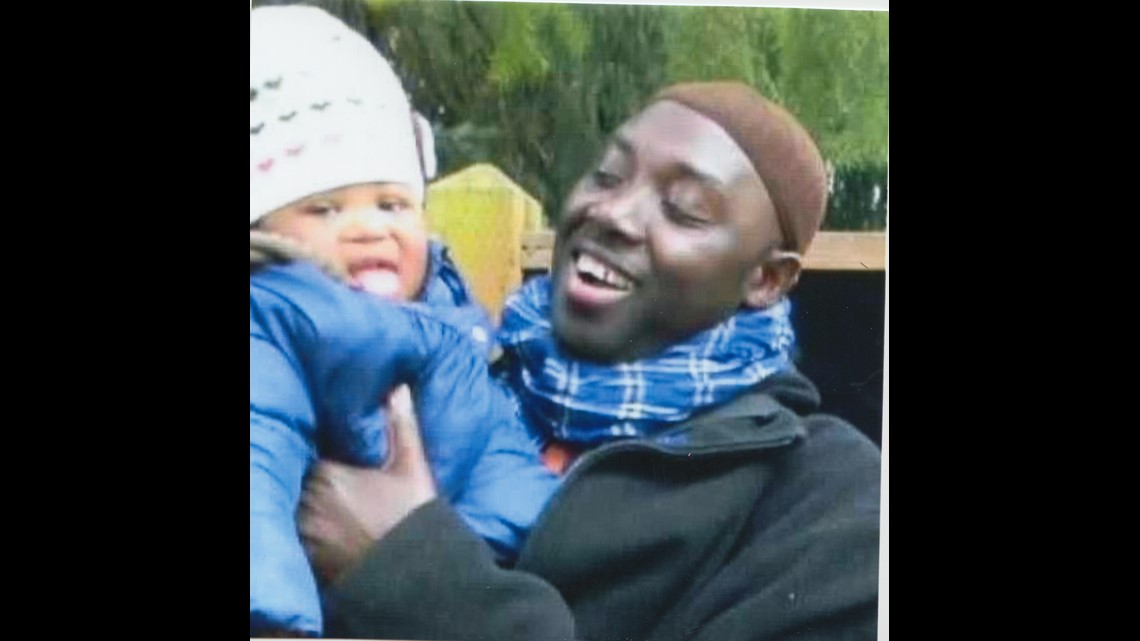

“I miss my family. I miss my wife. I miss my two kids,” said Jarju in an interview with KGW.

He is now living with extended family in The Gambia.

“It’s not easy. I can’t do it. I can’t do it without my family,” he said.

Jarju speaks with his wife and daughters by cell phone almost daily, but the signal is weak and video quality is poor.

“It’s horrible,” said Jarju.

Jarju is not the only person unexpectedly deported to The Gambia. Earlier this year, dozens of other men, living in the United States were forced to return to West Africa, according to media reports.

Bub Jabbi, 41, of Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin was deported to West Africa, according to ICE. He entered the U.S. in 1995 and overstayed his visa. He had no criminal history.

“I will not be apart from my husband nor allow my children to grow up without their father,” Jabbi’s wife, Katrina told the Wisconsin Rapids Tribune. Jabbi has two daughters, ages 5 and 1.

The deportations were made possible after The Gambia agreed to accept the return of its citizens in December 2017. The U.S. had issued visa sanctions against The Gambia in 2016 as punishment for refusing to accept its citizens back from the United States.

“Ensuring the countries facilitate the removal of their nationals who are subject to a final order of removal is a high priority for the Department of State and this administration,” said State Department Spokeswoman Heather Nauert during a December 2017 press briefing.

For the Jarju family, this case goes beyond politics and immigration policy.

“It’s very hard because not only is he gone, but we’re still dealing with the stress and the shock of all this happening,” said Andrews Jarju.

Elizabeth said she never got to hug her father goodbye.

“I miss him,” she said.

Have a tip for KGW investigators? Email investigators@kgw.com