Editor's note: This story was published on October 1, 2017

Tent City, USA is a KGW investigative project that explores who Portland’s homeless tent campers are and what led to the proliferation of tent camps across the city. Tent City, USA was reported and produced by KGW's investigative team: Kyle Iboshi, Maggie Vespa, John Tierney, Sara Roth and Gene Cotton. Infographics and multimedia design by Jeff Patterson.

As an endless, near-deafening stream of traffic flowed by, the oppressive July sun beat down on a small, green tent perched at the corner of Southeast Woodstock Boulevard at Interstate 205.

Inside, on a pile of quilts, pillows and backpacks, huddled a woman, two men and a dog.

“Come on, Luna! Come here, baby!” Willow called, waving to her 7-year-old brown-and-white pit bull panting in the back of the tent. “I want her by the door. It’s just too hot … there’s more shade on this side, too.”

The dog, still panting, walked around the inside perimeter of the tent and sat down near the unzipped opening.

“We wet her down,” said Willow, handing Luna’s red scarf to her boyfriend, Shorty, who held a small, half-empty plastic bottle of water. “This helps if we wet down her bandana.”

A few feet in front of the tent sat a cart, piled high with clothes, books, including an atlas of battles of the Civil War, and other belongings.

On top of that pile sat a square cardboard sign: “Homeless... Epileptic... Hard times… Need help! May God bless us all!”

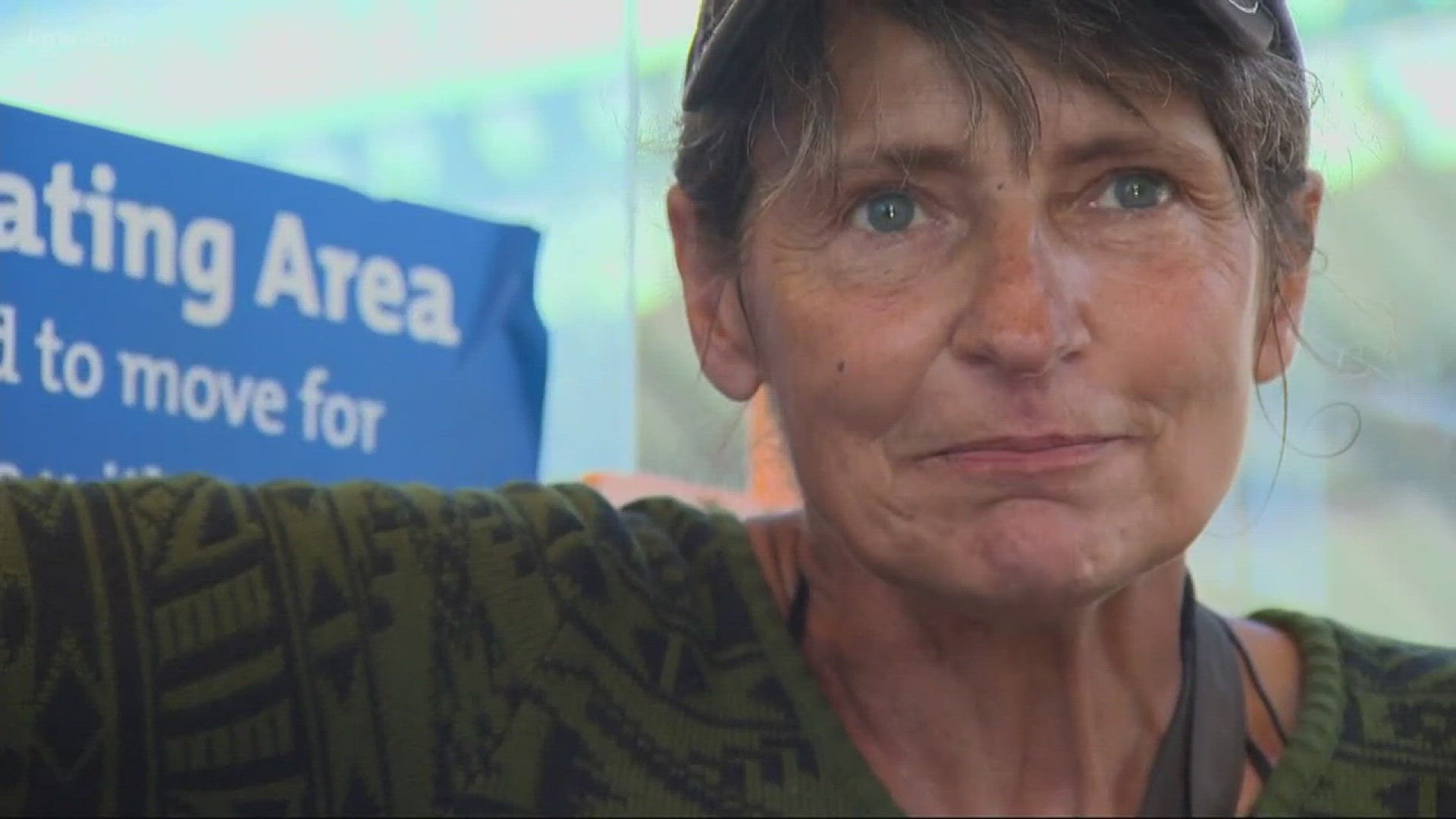

Willow, a 56-year-old mother of two, has been homeless in Portland, on and off, for nearly a decade.

Most of that time, she has been in a tent.

“When I was younger, it was like camping out,” she said. “But it’s not quite like that anymore.”

Walking with Willow: The struggle of running errands as a homeless camper

A week later, on a sunny Wednesday morning, Willow returned from her daily trek to a nearby convenience store for water and other necessities, back to her new home base, where about half a dozen other campers waited, guarding the group’s belongings.

A few days before, Oregon Department of Transportation crews told them they had to leave the state-owned patch of land along Southeast Woodstock.

Willow, Shorty and about half a dozen others had now set up camp off Southeast Foster Road, tucked between the Springwater Corridor and a small property owned by Portland General Electric.

Their camp was shaded by a few sparse trees.

Willow said the new camp provided a welcome retreat after her weekly epileptic seizures.

“It’s from a birth defect in my brain,” she said of her epilepsy. “I usually have really bad headaches. Sometimes I can’t talk from, you know, chewing my tongue. My tongue swells up.”

The seizures, which are aggravated by stress and lack of sleep, leave her tired and confused for a day or two afterward.

It’s cost her several jobs and, in turn, several apartments.

“But, you know, I’m kind of used to it,” she said. “I never remember a time when I didn’t have them.”

Photos: Willow's journey

Willow dreams of going back to school to refresh her sign language skills and become an interpreter, in part for the flexible hours.

For now she lives off disability checks, which amount to $700 per month.

“I’m usually the kind of person that takes it as it comes, and, you know, onward through the fog,” she said. “That’s all anybody can do really.”

On this morning, Willow had been seizure-free for three days.

She had two missions: to pick up a disability check and take Luna to the veterinarian.

Luna’s left eye was pink, swollen and oozing, the result of a recurring infection that’s lingered for more than a year.

“I’ll just use my sleeve,” she said, wiping away the pus.

Getting to the veterinarian will be no quick trip, in part, because of the physical distance.

Willow and Luna will have to walk nearly ten blocks, then ride the MAX train to Northeast 82nd Avenue and Broadway Street.

Beyond that, she can’t be positive the trip will work. It depends on whether the clinic has time for her.

As she walked, Willow reflected on how hard her life on the streets has become.

“This last winter was really harsh. It was probably the worst since I’ve been here,” she said. “One night we woke up and everything was deep in snow. That was kind of a trip. It tends to put you on edge.”

Nevertheless, she only sought respite in Portland’s emergency shelter system once.

“We stopped going to the shelters because we kept getting sick every time we went. Everybody’s coughing all night long,” she said. “I think I was sick for a month at one time with some kind of flu.”

Minutes later, Willow and Luna boarded the MAX Green Line, headed north.

“When I was first homeless, I stayed in the grassy area here and then right underneath that bridge,” said Willow, pointing to the landmarks whizzing past. “There were a lot of people, five to nine people.”

It was her first time being homeless in Portland but it wasn’t her first exposure to life outside.

Willow was born Grace Willette Rosson on Oct. 29, 1960 in Ventura County, California.

Her parents split early, and her mother married a man who drank.

She spent most of her childhood living with her biological father, who was “a jack of all trades” and worked odd jobs to support her.

In the summers, he ran an illegal marijuana grow operation in the mountains of Northern California.

“We lived in an actual cardboard cabin.” she said, laughing. “It was real thick cardboard and real thick heavy plastic, so it was waterproof. It had a dirt floor and a wood burning stove and five gallon bucket for toilet, and my dad built a little privy out of sheets, so I had my privacy.”

She was 13 years old and saw it as an adventure.

“I think back about childhood, and I was happiest when we had the least,” she said.

By 10:30 a.m., she’d arrived at the Northeast 82nd Avenue stop, a couple blocks from a small, one-story network of offices operated by the Portland Animal Welfare (PAW) Team.

The nonprofit provides free veterinary care to pets of owners living below the federal poverty line.

On most days, they require appointments. Willow didn’t have one, but a staff member named Hannah agreed to squeeze her in.

“And you go primarily by ‘Willow,’ correct?” Hannah asked, sitting across a small desk. “Do you have a phone number you can easily be reached at?”

After a few more routine questions, Hannah informed Willow her registration with PAW Team had lapsed and would need to be renewed.

Then she asked for identification and proof she’s on disability.

“My backpack was just stolen,” said Willow. “My IDs and stuff were in there.”

It’s a hurdle that plagues many in Portland’s houseless population. ID cards are often lost or stolen. Most don’t have enough alternative forms needed to get a replacement.

It makes getting housing, a job or, in this case, veterinary care, difficult.

On this Wednesday morning, it appeared to be one hurdle too many.

“Would you be able to come back for an appointment next Wednesday the 23rd?” Hannah asked.

Willow nodded and was directed downstairs for free food and pet supplies. Ten minutes later, she left.

“So, they said to come back in a week,” she said. “That’s great. At least she's going to be taken care of … I'll just keep cleaning it out with a wash, an eye wash.”

Next on Willow’s errand list: walking to JOIN at Northeast 81st and Halsey.

JOIN is a nonprofit that helps place homeless adults in affordable housing. Willow gets her mail there and was hopeful her disability check had arrived.

As she walked in, talk of money turned to talk of cruelty and the insults people hurl at campers as they walk or drive by.

One woman, she recalled, was ruthless.

“She said ‘Well, at least I worked, and I didn't lay on my back like you did!’ Like referring to that I was a prostitute or something … It's frustrating, frustrating that people would pre-judge,” she said.

It’s one of several aspects of life on the streets that Willow keeps from her kids.

Both her daughter and son are grown. Her daughter lives in Vancouver, Wash. Her son lives in Colorado.

“This is the first time he's ever been in a different state,” she said. “He misses his sister.”

Both know she’s homeless, she said, but neither is able to help her.

Their father passed away when Willow was 29. Like her current boyfriend Shorty, he was diagnosed with leukemia.

Willow said the disease moved quickly.

“He kept it from me, which I wish he hadn't,” she said. “I had even asked him if he was going to die and he assured, ‘Oh, no.’ And he died the day after I asked him that.”

The couple had been together more than a decade and ran a head shop in the San Fernando Valley area.

It was the only job Willow could keep between seizures.

She worked a series of part-time jobs in the decade after that, to support her two kids, moving them first to the mountains near Colorado Springs, then to Portland.

Both children graduated from Jefferson High School.

“I love my kids. They're the best thing I've ever done in my life,” she said.

Now, with only herself to support, Willow relies solely on those disability checks.

She arrived at JOIN just before noon, and walked out only a few minutes later, empty-handed.

The check was late and she was deflated but not surprised.

“Yeah, it's been six days late,” she said of past deliveries.

With no money and no medicine for Luna, Willow walked back to the Green Line stop to head south, toward her camp.

On board the train, she talked of friends who’ve managed to hold down jobs while living on the streets.

Suddenly, Willow’s speech began to lag.

“It’s up…” she said, before taking a long pause. “I'm having like a little bit of an absence seizure, like that thing I told you about before. I can't think straight.”

An “absence seizure,” or a petite mal seizure, is described by the Mayo Clinic as “brief, sudden lapses of consciousness … during which the patient may look like he or she is staring into space for a few seconds.”

In Willow’s case, it’s often a precursor to a grand mal seizure, the kind that makes a person drop to the ground and begin convulsing.

She’s afraid that’s coming.

“I need to take a pill and lie down,” she said.

The walk back to camp was slow and quiet, punctuated only by a stop in that convenience store.

“I need something to drink,” she said.

She bought two iced teas and a poppy seed muffin wrapped in cellophane.

It would likely be her last meal of the day.

She waited a few minutes for a break in traffic before crossing Southeast Foster and walking back to her camp.

Fellow campers, seeming well versed in the routine, helped lay out blankets under a tree.

Willow took a pill and laid down.

After three hours wasted on two unsuccessful errands, her day was done.

The struggle of surviving on the streets had knocked her back to square one, where she would stay until the symptoms of epilepsy subsided.

That Wednesday night, as Willow slept under that small patch of trees in her temporary home along Southeast Foster Road, a grand mal seizure arrived just as Willow predicted.

The next day, crews ordered her group of campers to move again.

Read more:

Published Oct. 9, 2017