Editor's note: This story was published on October 1, 2017

Tent City, USA is a KGW investigative project that explores who Portland’s homeless tent campers are and what led to the proliferation of tent camps across the city. Tent City, USA was reported and produced by KGW's investigative team: Kyle Iboshi, Maggie Vespa, John Tierney, Sara Roth and Gene Cotton. Infographics and multimedia design by Jeff Patterson. Click to view the project website

Portland is made up of many neighborhoods, each with its own distinct personality. Yet homeless tent camps plague them all.

Tents crowd Inner Southeast, among renovated warehouses. North and Northeast Portland’s parks are home to several camps. The Springwater Corridor in outer East Portland sees sporadic influxes of camping communities. Campers set up shop in Southwest Portland, along the waterfront and downtown. Campers pitch tents throughout industrial Northwest and under bridges in the tony Pearl District. Camps line the banks of the highways that run through the city from east to west and north to south.

The camps aren’t just comprised of tents. Many are also filled with garbage, drug paraphernalia and human waste.

Residents across Portland say they are increasingly frustrated and afraid, as tent camps encroach closer toward their homes. The homeless campers are constantly on the move, pushed around by city-funded sweeps.

The scope of homelessness in Portland hasn’t changed much over the past few years; the number of homeless people in Multnomah County has hovered around 4,000 since 2009. But homeless camping has become far more visible, impacting how other city residents feel. One-third of Portlanders said they are considering moving out of the city due to homelessness.

KGW’s investigative team spent three months conducting an in-depth analysis of homeless tent camping in Portland. Reporters surveyed 100 people living in tents to find out who is camping on Portland’s streets and why. A crew spent a day with a homeless woman, learning first-hand the difficulties she faces completing basic tasks. And city leaders, police officers and homeless advocates explained the specific policies and circumstances that spawned the pervasive, public problem Portland faces today.

Photos: Tent City, USA

Who are Portland’s tent campers?

Out of Multnomah County’s 4,177 homeless people identified during the February 2017 point-in-time homeless count, 1,668 sleep outside – 12 percent fewer than two years ago, due in part to hundreds of new shelter beds added since 2015.

The City of Portland doesn’t know exactly how many of the homeless people sleeping outside stay in tents, but the city and county’s Joint Office of Homeless Services says there are at least a few hundred every night.

Although tent campers make up a small percentage of Portland’s overall homeless population, they are undoubtedly the most visible and controversial group of homeless residents. The issue has only gotten worse in recent history.

“Those structures became more prominent last year, in highly visible locations,” the county noted of tent camps and other temporary homeless structures, in its 2017 point-in-time report.

Each week, Portland residents report hundreds of homeless camps near businesses, homes, schools and parks.

“They stay for weeks at a time,” said Gary Rambeau, who lives in outer Southeast Portland. “The last one we had was well over six months before they were able to get him out of here. He left a considerable amount of trash on the side of the road, defecated all over the neighborhood. I caught him stealing water out of my faucets. Jumping over my fence to see what was behind my backyard. They’ve broken into my home once. So yeah, it’s pretty aggressive.”

Sgt. Randy Teig, who patrols homeless camps in Northeast and Southeast Portland with the Portland Police Bureau’s East Precinct Neighborhood Response Team, said he hears from residents who are petrified of camps moving into their neighborhoods.

“It’s all rooted in the fear of the unknown,” he said. “They don’t know who’s in that tent. They’re a property owner or a renter and there’s this person who just showed up.”

Yet no quantitative data has been collected specifically about Portland’s tent camping population until now.

KGW surveyed 100 homeless tent campers between July and September 2017 in every quadrant of the city. Participants were asked how long they’ve lived in Portland, how long they’ve lived in a tent, where they were living before, and why they live in a tent instead of other sheltered locations.

Note: Interactive works best on desktop. Mobile users, tap here for results

The answers run counter to perceptions many have of Portland’s tent campers. The majority are not transients who travel to Portland from out of state or even out of the city. They often aren’t newly homeless. And many have slept in a tent in Portland for quite some time.

The last question KGW asked was, “If given the choice tonight, would you rather sleep in a shelter or a tent?”

Nine out of ten people said they would choose a tent. Responders provided a litany of reasons, including independence, sanitation, and the ability to stay with friends or pets. Some – mostly women – said they feel safer in a tent that they can close up at night. One in three said they can’t cope with other shelter residents and rules such as sobriety and curfews.

“I don’t get along with people very well. I’m highly antisocial,” explained Tim Robinson, 40, who was camping in inner Southeast Portland.

“I don’t have to be up at seven in the morning and then kicked back onto the streets,” another camper said.

Some said they are trying to hide their situation from family.

“My oldest boy, he lives up on Holgate here but he’s got five kids of his own and he’s got his own family,” one man said. “I don’t let onto them how I’m not doing that good.”

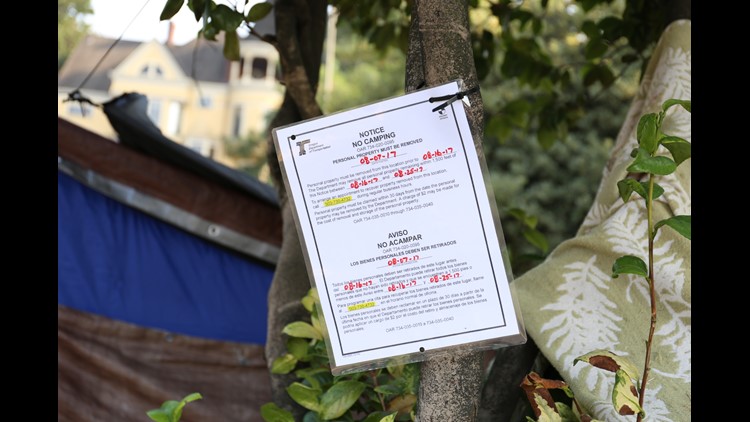

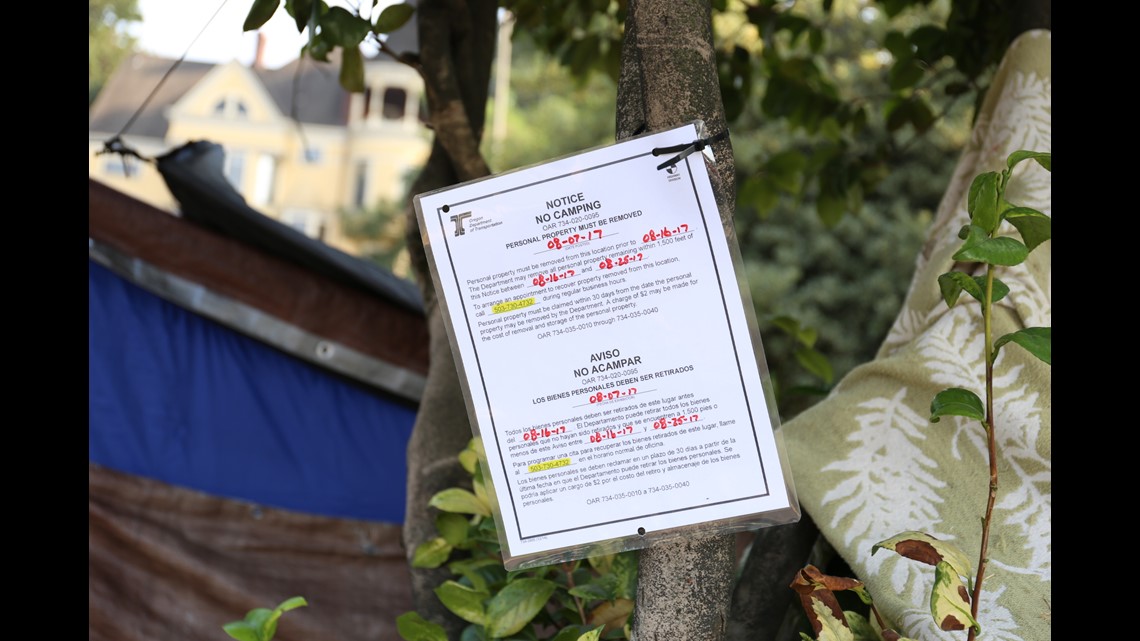

None said life in a tent is calm or simple. A city-contracted company routinely clears out camps, with a list of planned sweeps posted weekly online. Campers can never settle in; they must be ready to move on short notice. Some return to their camp sites to find their belongings rounded up during a sweep and moved miles away to a storage facility.

Some said they would do anything to get out of their tents.

“I want to be working. I want to be part of society. I want to be able to watch TV, you know. Take a shower, have heat, have a bed,” said a man who was camping near the Rose Garden in Southwest Portland. “It’s a nightmare out here.”

The daily struggle for many includes degrading interactions with passers-by.

“People that are not living on the streets, they look at you like you are scum,” one homeless camper said. “Not everybody is like that but a lot of them will look down at you like, ‘Who are you and why are you around me?’”

“They look at us like a zoo animal,” said Catherine Jensen, who was camping near the east end of the Ross Island Bridge.

Others said they’re verbally attacked.

“You hear people throw out rude remarks, saying, ‘Get a job, you filthy bums,’ or ‘Get off the streets,’ or ‘Go back to where you came from,’” another camper said.

Willow, a 56-year-old woman who camps in Southeast Portland’s Lents neighborhood, has experienced interactions like this many times over her 10 years of on-and-off homelessness. But verbal barrages pale in comparison to the struggle she faces trying to complete routine tasks while living in a tent.

Willow’s Story

On a sweltering afternoon in late July, Willow – whose legal name is Grace Willette Rosson – was huddled in a green tent on a patch of grass near Interstate 205 and Southeast Woodstock Avenue. The tent provided shade but no break from the heat for her and her tent mates: her boyfriend, a friend, and her 7-year-old panting pit bull, Luna.

As Willow wet Luna’s bandana to cool the dog, she explained that she used to enjoy camping but as she gets older she just wants a safe place to stay. Willow suffers from epileptic seizures and her boyfriend, Shorty, is losing a battle with leukemia.

Like many tent campers in Portland, Willow has been living in the city and sleeping in a tent for a long time. She moved to Portland when her children were in high school. Her seizures made holding down a job difficult. She eventually couldn’t keep up with rent payments. Although she’s on waitlists for affordable housing, she says right now she has no other option than the tent.

For Willow, life inside a tent is difficult enough. Errands that many homeowners don’t have to think about can be lengthy battles.

Twice a month, Willow must travel to get her $350 disability checks from a mailbox at JOIN, a homeless services center on Northeast 81st Avenue. Every time, she hopes she stays seizure-free.

On the day KGW joined her, Willow was not so lucky.

Photos: Willow's journey

Despite Willow’s struggles, she has more protections now than she did five years ago. Although she moves her tent every few days during city-mandated sweeps, she, and hundreds of others, are still allowed to camp in city limits.

Two policies and an economic shift changed how Portland manages tent camps, allowing for the sprawling encampments in the city today.

How did we get here?

Portland has long been considered a friendly city for homeless people, with mild weather, open space and an interwoven network of nonprofits that offer food, shelter and services. But as Portland grew, the network couldn’t keep up.

Population boom; rent spike

Following the Great Recession in the late 2000s, Portland became a magnet for new residents looking for a quirky, less-expensive city. As Portland’s population surged, development proliferated from the city’s core to its outer limits. Rents rose far faster than incomes, leaving many tenants unable to keep up with rent increases. This contributed to a new group of homeless residents: One-third of Multnomah County’s homeless population has been homeless for less than a year, according to the 2017 homeless count.

The growth also exposed areas of the city where homeless tent campers had been hidden before.

“There are fewer out-of-the-way places if people want to live in a tent,” said Marc Jolin, director of the Joint Office of Homeless Services.

That made tent camps far more visible, according to Portland Police Sgt. Randy Teig. He said that by 2014, tent camps appeared to have taken over. At one point, his team counted 600 tents just on the Springwater Trail, with an average of 2.5 people per tent.

“I went down to the trail one day and was like, ‘What the heck just happened out here?’ It seemed like it was overnight. Obviously, it wasn’t,” Teig said.

Growth was just one factor in the proliferation of tent camps. Two policies also had a significant impact.

1. Anderson v. City of Portland

The first policy that drastically changed how the city of Portland manages tent camps stemmed from the Anderson v. City of Portland lawsuit, filed on behalf of several homeless campers in 2008.

At the time, the Portland Police Bureau was the primary agency responsible for cleaning and moving illegal tent camp sites within the city. But Anderson vs. City of Portland contended that Portland police failed to recognize homeless tent campers’ constitutional rights.

In 2012, the police bureau entered into a settlement that outlined several stipulations for cleaning camps, including requirements for photographing and videotaping cleanups, moving property to a storage location, limits on when camps can be swept, and what kind of notice the city had to provide before sweeps.

Those requirements were confusing, cumbersome and expensive for the bureau. Furthermore, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration questioned whether police were properly equipped to safely handle camp cleanups.

The police bureau decided to turn over responsibility of cleaning camps to the property owners, meaning the city bureaus that own property were suddenly responsible for keeping homeless camps off city land.

The sudden change and new settlement requirements meant city bureaus were also confused about how to legally clean up camps.

Current Portland Mayor Ted Wheeler says years of futility followed.

“Our city has been inconsistent and I would even argue ineffective in addressing the tent issue,” he said. “For a number of years, we weren’t even enforcing overnight camping codes.”

2. Mayor Charlie Hales’ Safe Sleep policy

During the last two years of Portland Mayor Charlie Hales’ one and only term, Portland housing prices skyrocketed and the city council was under immense pressure to help people at risk of losing their homes as well as the many homeless people on Portland’s streets. In 2015, Hales announced a state of emergency for housing and homelessness to open more shelter space, which was renewed on Oct. 4, 2017.

Then, in February 2016, he unilaterally enacted the Safe Sleep policy to ease restrictions on where homeless people could sleep. The policy gave people free reign to spend the night undisturbed in tents or sleeping bags on city sidewalks.

The Safe Sleep policy was short-lived – Hales killed it six months later – but it further confused an already chaotic situation and led to widespread permissiveness of homeless camping across the city of Portland.

Sgt. Randy Teig said the guidelines effectively stopped police from taking any action against homeless campers.

“Officers did not know what they were allowed to do,” Teig said. “So the only thing a reasonable supervisor can do is say, ‘I don’t know what you’re allowed to do so we’re going to do nothing.’”

Safe Sleep also led to far more visibility among Portland’s homeless tent campers, many of whom relocated from hidden locations on the outskirts of the city to more populated areas.

“That process kicked off a real shift on the ground around where people chose to locate with tents,” said Marc Jolin with the Joint Office of Homeless Services.

Hales denies that Safe Sleep had a significant impact on visible tent camping. He cited studies of other large cities such as San Francisco and Seattle that showed larger increases in homelessness there than in Portland, based on 2017 homeless counts.

“Arguing about Safe Sleep is a sideshow at best,” Hales said. “Homelessness is up sharply across the western states. Portland has managed better than most.”

Although the Safe Sleep policy ended, the legal ramifications of the Anderson v. City of Portland settlement remain. In addition, rents keep rising and Portland keeps growing, leaving the current city administration faced with the seemingly untenable task of reducing the size and visibility of Portland’s established tent camping population.

The future of Tent City, USA

Over the past two years, Portland has refined its approach to managing the homeless population.

The city and county-funded Joint Office of Homeless Services oversees government-funded homeless initiatives. To help people living outside, the joint office added 650 more shelter beds since 2015. Several shelters now accept couples and pets.

The One Point of Contact system now acts as a hub for residents who want to report a problematic camp anywhere in Portland.

The city’s system for sweeping homeless camps became more coordinated. Since October 2016, the planned weekly clean-ups have been posted online and a map shows the location of each reported camp. Clean-ups have increased from an average of six per week to more than 40. Police regularly patrol camps and arrest people who have violated laws unrelated to homelessness.

“It is burdensome and it is expensive,” Sgt. Teig said. “But we have a system now that is infinitely better than it was. In the last six months, we’re starting to hit our stride a little bit.”

But even with more beds, shelters remain at capacity and most have waitlists. Resident reports are informative, but legal and staffing limitations mean that police and contractors mainly target camps that threaten public health, safety, or the quality of neighboring residents’ lives.

Mayor Wheeler maintains that in the long term, tents are not an acceptable place to live.

“We don’t believe sleeping in a tent is a humane alternative to living in a warm, dry place with access to water, access to showers, access to laundry and access to social services that can actually help people get out of homelessness,” he said.

But Sgt. Teig explains that may not be what some tent campers want.

“A lot of the folks who are out here, they don’t really want services. They want to be left alone by the police and other people. They want to do their thing,” he said.

Many homeless tent campers agree with Teig.

“Out of 10 people you talk to, I would probably say three or four of those people would probably tell you that they like being homeless because of the freeness that we have,” a camper told KGW. “A lot of people just don’t really want to have the responsibility of paying a bill or paying a car note or paying a house payment or something along those lines. So they would rather just live in a tent because it’s easier to just set up a tent and live.”

Read more:

Published Oct. 9, 2017