A Vancouver teen died after a fentanyl overdose at school, but the district didn't tell parents or police what happened

KGW used public records and conversations with the student’s family to piece together what happened in a high school bathroom, and why it wasn't shared

On May 3, 2022, just after 8 a.m., a staff member at Hudson’s Bay High School in Vancouver, Wash. called 911.

"I need an ambulance immediately, I’ve got a student overdosing in the bathroom,” she said. “I have multiple administrators, district resource officers, and a nurse with the student at this time. I believe they are administering Narcan."

School officials had found a 16-year-old girl unresponsive in a bathroom stall.

The school was placed on lockdown. A district resource officer wrote in a report that they found burnt tin foil and blue pills, likely fentanyl, on the girl’s clothes.

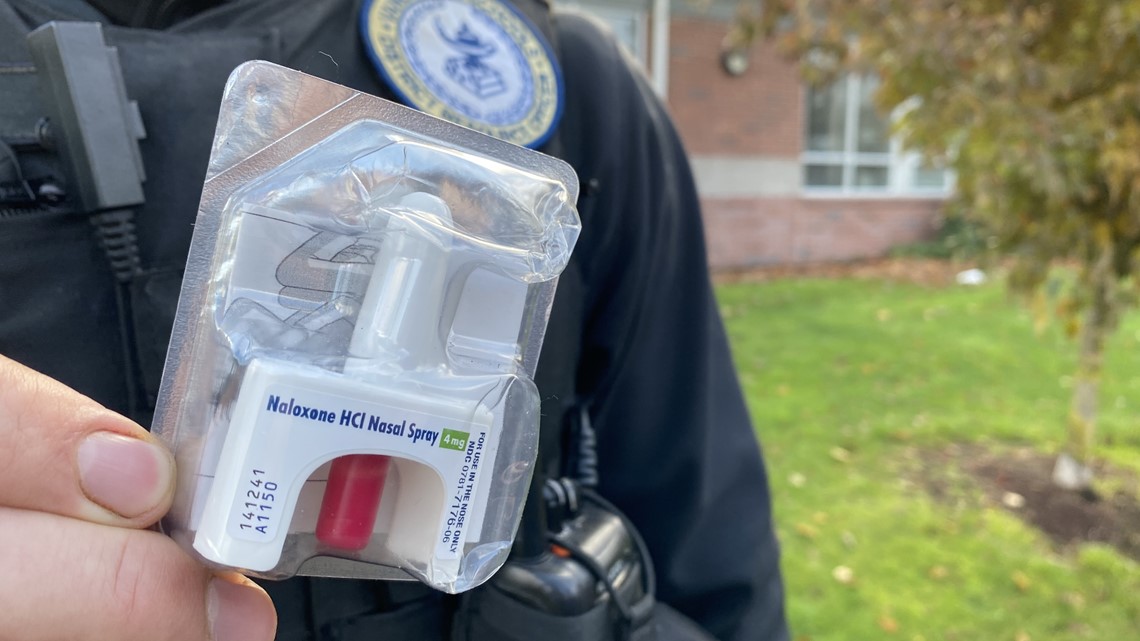

A school nurse and a medical responder both used Narcan – a brand of naloxone, an opioid reversal medication – to try and save the girl’s life.

She was rushed to PeaceHealth Southwest Medical Center and later transferred to Randall Children’s Hospital in Portland, where she died six days later.

Even though the overdose occurred on school grounds, the Vancouver School District never told families or staff that fentanyl was found in the bathroom, or that the girl died of a fentanyl overdose.

Vancouver Police were not called to investigate the overdose and student’s death, and even now – seven months later – most people don’t know about it.

For months, KGW has used public records and conversations with the student’s family to piece together what happened in that high school bathroom and examine the impact of the school district’s decision to not publicize news of the overdose or call police.

Our Reporting Process

KGW first learned about the student’s death in June after receiving an anonymous tip.

The source said they were frustrated very few other people knew what happened, as families should be aware so they can talk about the dangers of fentanyl in schools and the community.

KGW then filed numerous public records requests with the Vancouver Police Department, emergency medical response agencies, hospitals, medical examiner’s offices, state agencies and Vancouver Public Schools.

The responses confirmed that a 16-year-old girl died of fentanyl poisoning at Hudson’s Bay High School.

Once known, KGW Investigative Reporter Evan Watson wrote a letter to the girl’s parents, who said they’re heartbroken by the loss of their daughter.

Watson met in person with the student’s mother, who asked that KGW not use her daughter’s name in this report, out of respect for her family’s privacy.

However, she said KGW should share what happened, as she believes people should know and she wants to help prevent the potential death of another child.

What Was Shared

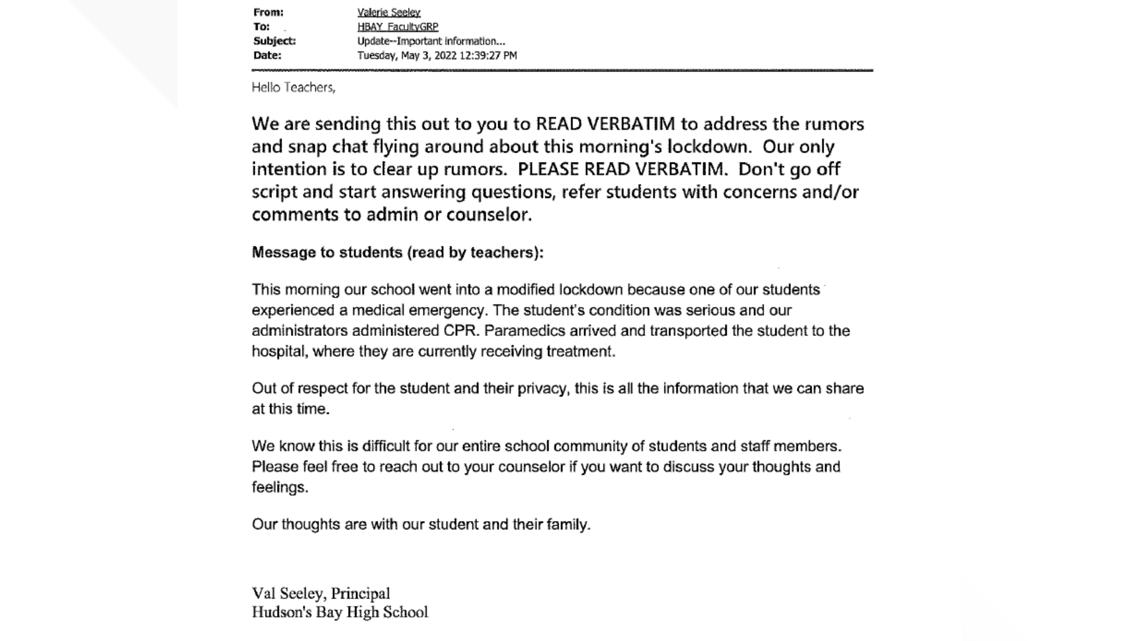

On the day school officials found the girl unresponsive in a bathroom, Hudson’s Bay High School principal Val Seeley sent an email to families.

It said a student experienced a "medical emergency" at school and was taken to the hospital.

According to documents produced by the school district through public records requests, Seeley sent the same message to HBHS staff members, but it was prefaced with a bolded message:

"We are sending this out to you to READ VERBATIM to address the rumors and snap chat flying around about this morning's lockdown," the email said. "Our only intention is to clear up rumors. PLEASE READ VERBATIM. Don't go off script and start answering questions, refer students with concerns and/or comments to admin or counselor."

One week later, Seeley sent another email to families and staff in which she identified the student and shared the news of her death.

"I am deeply saddened to share with you that the Hudson’s Bay student who experienced a medical emergency last week, *******, passed away yesterday," Seeley wrote.

In the email, she offered counseling and support services for anyone who needed them. She also asked others to be patient and respectful as people grieve in different ways, and she expressed sympathy for the student’s family.

Neither Hudson’s Bay High School nor Vancouver Public Schools shared that the student died of a fentanyl overdose, or that fentanyl was found at school.

When asked why parents weren’t informed, VPS Superintendent Dr. Jeff Snell told KGW the district is not required to share this information.

"I don’t know what parents would want exactly," Snell said. "If there’s an overdose, do we just say a student overdosed from fentanyl at the school? I think that we as a school have a responsibility to be thoughtful about that and engaged with the family of the person who did that, in terms of what’s disclosed."

KGW asked Snell if he believes the district should leave the decision of whether to share information about an overdose or the presence of fentanyl at school to the families of any involved student.

"We’re trying to balance, like you’re saying, the desire of an entire community to understand what’s happening versus the desire of a family that’s [been] through something horrible, right?"

Snell said that a single fentanyl overdose may not reach the district’s standards to inform parents of the drug’s presence in schools.

"If we’re working with law enforcement and fentanyl is running rampant and we’re having multiple cases, we’re going to have to share that information in a way that’s going to allow families to understand the risks that are happening and to have those conversation with their kids," Snell said.

He also suggested that students and staff may already have a sense that fentanyl could be involved when there’s a medical emergency lockdown at school.

"We have these situations like you’re describing and there’s some kind of knowledge and you just need to kind of work with what kids would probably already know at some level," Snell said. "And then how do you respect the privacy and the law related to that?"

Snell explained that a primary concern in notifying the community about a fentanyl overdose is a student’s privacy.

However, for other dangers – like a student bringing a gun to school – school districts often share that information without the student’s name.

Marsha Malsam, a parent and fentanyl awareness advocate, thinks school districts should take that same approach when talking about fentanyl.

"If we want to put our head in the sand, we’re just going to keep seeing more overdoses and more losses at every age level," Malsam said. "So, we have to talk about it."

Malsam serves as the Chief Executive Officer for the Rayce Rudeen Foundation, an organization that works on fentanyl awareness throughout Washington, talking with schools and working with the DEA and lawmakers.

Rayce Rudeen was Malsam’s nephew. He died of a fentanyl overdose in Seattle in 2016.

"We have a problem in our country, and it shouldn't be an embarrassment because it's in your school," Malsam said. "But how are we going to fight it in our school and how are we going to avoid a horrific story instead of reacting?"

In her conversation with KGW, the mother of the student who died at HBHS said she would’ve been alright with the school district sharing that a student died of fentanyl – even if people could draw conclusions between the death of her daughter and the announcement – because the community should know about the danger.

Federal agents who investigate fentanyl cases agree this awareness is crucial.

Jake Galvan, acting special agent in charge for the DEA field division in Seattle, said he sees how fentanyl pills have permeated every community. He said it can be dangerous for people to think overdoses won’t happen in their city, or in their school.

"Transparency and communication – it is the most important thing because we need to save lives, and the way to do that is to get the word out of how dangerous this is," Galvan said.

An Empty Investigation

About a month after her daughter died, the HBHS student’s mom called Vancouver Police, asking them to investigate how her daughter obtained fentanyl.

She explained to a Vancouver Police officer that her daughter had been a 'Straight A' student and a member of the volleyball team, but she got caught up with the wrong people.

Doctors told her that her daughter died of a fentanyl overdose. She was proud that her daughter was an organ donor and was able to help others through her donation.

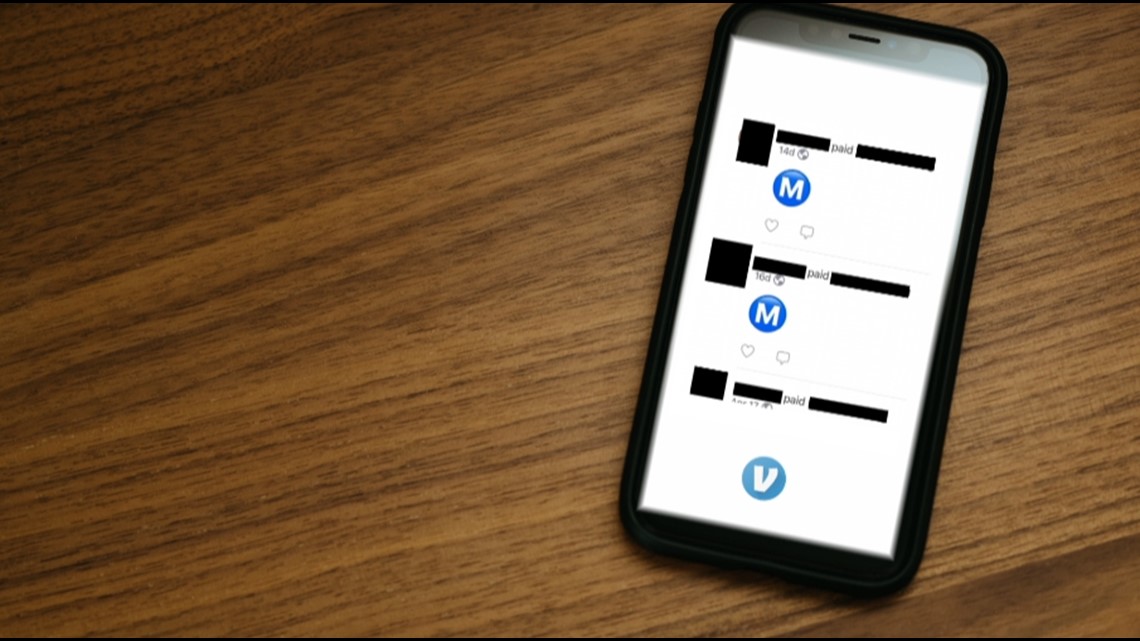

The mother also gave police a critical piece of information – screenshots from Venmo, an app used to send and receive money.

The public screenshots showed her daughter paid a man and captioned the payments with a blue circle emoji with the letter ‘M’. The payments were sent about two weeks before her death.

Fentanyl pills, commonly called 'blues' on the street, are often blue tablets marked with the letter 'M' to look like oxycodone medication.

The police reports detail how a Vancouver Police detective talked with the girl’s friends, contacts and family over the next two months, but he couldn’t make an arrest for one significant reason.

Police didn’t have the blue pills as evidence. Vancouver Police officers were never called to the emergency in the HBHS bathroom in May and they didn’t start an investigation until about a month later, when the girl’s mother called them.

Therefore, officers weren’t able to develop probable cause to arrest anyone, even though they had leads on who may have provided the fentanyl that ended up killing the high school student.

Of note, a VPD spokesperson said the school district stopped staffing Vancouver police officers at schools in the early stages of the pandemic and the district chose not to renew their contracts.

A VPS release from September 2021 says: "Due to the impact of the pandemic and increased staffing needs at CCSO and VPD, contractual agreements for SROs weren’t renewed for the 2020-21 and 2021-22 school years."

Instead, VSD uses district resource officers, who function as school security.

KGW asked Superintendent Snell why the school wouldn’t always call police to investigate when fentanyl is discovered on school property. Snell said he couldn’t answer why that didn’t happen in this situation.

"I don't know specifics about the case," Snell said. "I think you would have to ask other people or look at the situation."

Multiple Vancouver Public School spokespersons said the district cannot answer specific questions about the HBHS student’s overdose death due to FERPA and privacy concerns.

Galvan, while saying he can’t speak to this specific case, said that from a law enforcement or DEA perspective, any delay in calling police makes holding anyone accountable for supplying fentanyl difficult.

"With any investigation, time is of the essence, so the sooner that investigation starts, the better it’s usually going to be for a positive outcome," Galvan said.

The Fentanyl Threat in Schools

Since May, Vancouver Public Schools has overhauled how the district prepares for a fentanyl overdose.

District resource officers, along with nurses, now carry or have access to Narcan. The opioid reversal medication is now available at all Vancouver public schools, not just high schools, after VPS changed its policies.

Nurses also introduced a new system of logging and tracking when Narcan is used, when it needs to be replaced, and where it’s available.

"It seems to be a growing concern, right, and so if there are growing concerns, we want to make sure we’re expanding the services we have to potentially address those," Snell said.

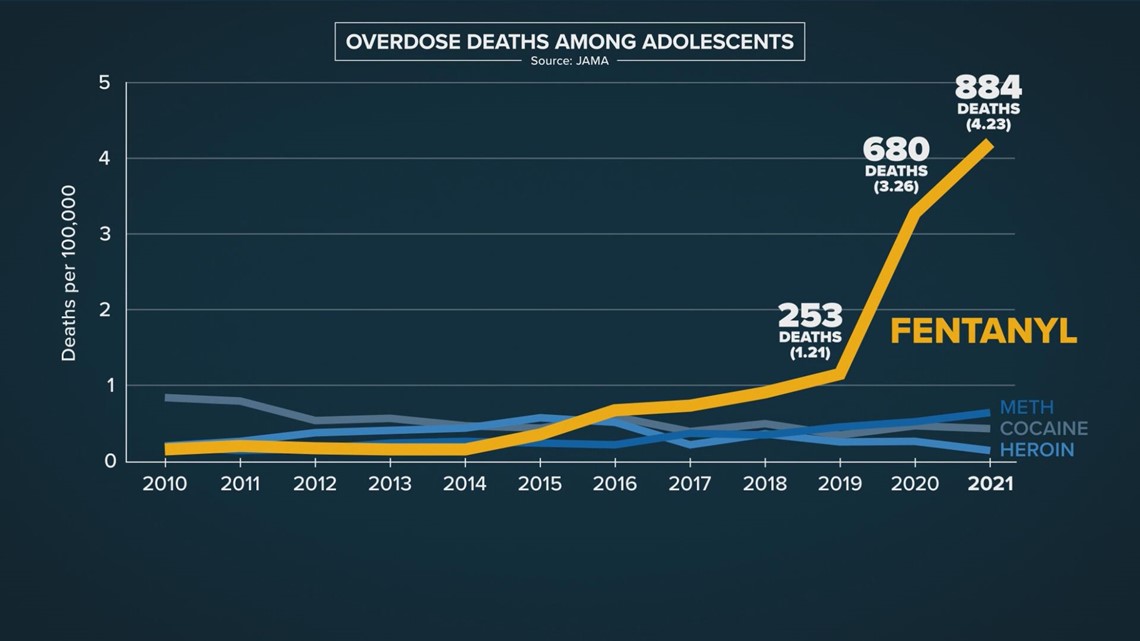

Nationally, teenage overdose deaths from fentanyl more than triple between 2019 and 2021, according to peer-reviewed research published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Fentanyl-involved deaths among adolescents increased from 253 to 680 to 884 in that three-year span, far outpacing every other type of drug studied, with reported deaths from those drugs remaining relatively flat.

New DEA laboratory testing showed that 6 out of 10 fentanyl-laced fake prescription pills contain a “potentially lethal dose of fentanyl,” an increase from DEA’s 2021 announcement that 4 in 10 pills contained a potentially lethal dose.

Washington is one of several states that requires many schools to have opioid reversal medication on hand, something Malsam said is needed, based on the proliferation of synthetic narcotics in recent years.

“Part of [the Rayce Rudeen] Foundation’s work is we do naloxone training, and I’ve heard parents and administrative staff say we don’t have drugs in our school,” Malsam said. “That’s not facing reality. It’s there. It’s in every school. It’s what each school does to handle it that will make the difference.”

Washington’s state requirement for naloxone in schools, however, is limited.

Only school districts with more than 2,000 students are required to stock opioid reversal medication, and among those districts, it’s only required in high schools.

There’s no set funding for how schools obtain naloxone, so many districts often rely on donations from medical providers or nonprofits.

And crucially, the Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction – the state education agency – does not track when school officials use naloxone, so there’s no way of knowing how many children may be overdosing, or how prevalent fentanyl is in schools.

"We know metrics really help us have better education on how to be more proactive and how to educate the community better," Malsam said. "It's a shame we aren't tracking it in a very confidential way just to [have] the numbers."

Snell said VPS is trying to be proactive, sending out messages to families about the threat of fentanyl and what to look out for, explaining that informing parents and the public about the danger is crucial.

KGW asked Snell: Wouldn’t the most poignant time to share that message be directly after a fentanyl overdose at school, as families could be more likely to take the warning seriously?

"Certainly, in some situations it could be, yeah," Snell said, without answering if it would have been more effective following the student's death in May.

Malsam said that’s not enough – advocating that people should always know about fentanyl overdoses in public spaces like schools to raise awareness and decrease stigma. Simply put, she said families should be talking about this.

"The highest danger is that this will happen again," Malsam said. "If people don’t know this is happening, how is it going to stop."