Psychiatrist shortage is a national crisis as need for mental health care grows

Oregon reportedly has fewer than 10 psychiatrists per 100,000 people.

A mental health care crisis is gripping our nation.

There is still a deeply-rooted stigma around mental illness, but that stigma is slowly starting to crumble. Meanwhile, the demand for psychiatric services is increasing.

People can’t access the care they so desperately need, and the limited number of providers is spread unevenly across the country, mostly concentrated in urban areas on the east and west coasts.

That weighs heavily on all Americans battling mental illness - and on the American health care system as a whole.

We dug into the shortage of psychiatrists in our region and around the United States.

A lack of access

Dr. George Keepers, chair of OHSU’s Department of Psychiatry, says access to psychiatric care has been a problem for decades. There have never been enough psychiatrists, and there may never be.

Keepers says it is clearly a crisis, one that is intensifying as more Americans are seeking mental health care.

National Alliance on Mental Illness data shows one in every five adults in the U.S. has some form of mental illness. About one in 20 lives with a serious mental illness; that is roughly 13.6 million people.

Data also shows 60 percent of adults with mental illness didn’t receive any mental health services in 2017, a trend that’s continued for years.

The mounting shortage is causing treatment delays like a Vancouver mom, Kimberly Berry, experienced with her daughters, along with a lower quality of care.

Kimberly's two daughters

“My oldest daughter has bipolar disorder and she has various different anxiety disorders - generalized anxiety, phobia-specific anxiety and she has social anxiety,” said Kimberly Berry.

“My youngest daughter has been diagnosed with ADHD, DMDD-- which is a mood disorder and it’s on the spectrum. A lot of people don’t know mood disorders are on the spectrum. And then she also has separation and general anxiety disorder.”

Berry learned to be a fierce advocate - because she had to.

“If you don’t, you will get trampled on and the system will eat you up,” she said. “It just requires a high level of resiliency and that’s not easy to build.

"When you’re holding your child in your arms that’s begging for death and wants to die. Or you’re standing in an emergency room, standing over your child who just overdosed and thinking, 'My God ... I can’t lose you.'”

She and her girls have walked through the darkest of times together. As a mother of two daughters battling mental illness, she says she’s felt a great deal of despair. Many times she’s been fed up, and has wanted to give up.

“Because you’re stuck. And I think that’s the hard part, is that you are powerless. And you see that your children are sick and there’s nothing you can do about it, nor can you get them the help that they need.”

Millions of Americans are fighting that same uphill battle. They spend countless agonizing days searching and waiting for psychiatric care.

“When my oldest daughter went into psychiatric crisis it took us four months, I think, to get our initial intake after we were released from a hospital,” Berry said.

She was told they were lucky. Many people in Oregon and Southwest Washington wait much longer.

Unfortunately, Berry said, sometimes the psychiatric care that finally becomes available isn't the best possible care.

“It’s a waiting game. And what you’re trying to do then is just triage the symptoms of the person that you love or within yourself. You’re just trying to get through every moment.”

When someone is in crisis, every moment matters.

“The studies show us that every moment that goes by that we don’t have the earliest point of intervention, it can take so much longer then to recover and stabilize,” Berry said. “When you can’t get access to the people that can help you, it’s so defeating and it’s so isolating and frustrating.

It's much more challenging to access care in our country's behavioral health model than it is our medical model, Berry says, because the two are viewed separately.

"We don't treat things from the neck up the same way we do from the neck down," she added.

Berry said therapy through a psychologist or other behavioral health specialist is ineffective if someone with mental illness isn’t stabilized.

There's another waiting period people suffering with mental illness confront: Prescriptions for psychiatric medications are hit-and-miss because there’s no definitive way of knowing what will work for each patient. In the meantime, most of those medications carry side effects.

Inadequate workforce

Dr. Keepers said it’s typical for people to wait upwards of five months to see a psychiatrist, even when they have severe conditions.

The amount of time psychiatrists have to spend with patients is being cut drastically.

Psychiatrists used to spend between 30 and 60 minutes with each patient to gather history, thoroughly review their condition, assess social issues involved with their care, and discuss medications, Keepers said.

"In a lot of organizations, that time has been reduced to about 10 minutes. And it’s really impossible to do good, comprehensive psychiatric care in such a short period of time,” Keepers told KGW.

This study by the National Council of Medical Directors says there is an inadequate workforce to deliver safe and effective care in outpatient and inpatient psychiatric programs. It also says the reduced supply and limited opportunities for training programs are leaving the current workforce less prepared to take on innovative approaches to health care reform.

It’s playing out in hospitals across the country: This shortage, coupled with shrinking inpatient services and beds, is sending more people to emergency rooms because they have no other choice. That becomes incredibly expensive for health care systems and for American taxpayers.

“When there are inadequate psychiatric services available to people, they have no choice but to seek emergency care. And as a result of that our ERs are filled with patients who have psychiatric conditions that emergency rooms are not designed to deal with and for whom there’s no actual referral,” Keepers said.

Underserved communities

This 2018 report by Merritt Hawkins, a physician research and consulting firm, shows there are only about 30,450 general psychiatrists actively practicing in the US. That number excludes specialties of child and adolescent psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry and addiction psychiatry.

According to data from the National Council Medical Director Institute in a report titled 'The Psychiatric Shortage: Causes and Solutions', 77 percent of U.S. counties are underserved.

The top five most populous states with the highest concentration of general psychiatrists are California, New York, Texas, Pennsylvania and Florida.

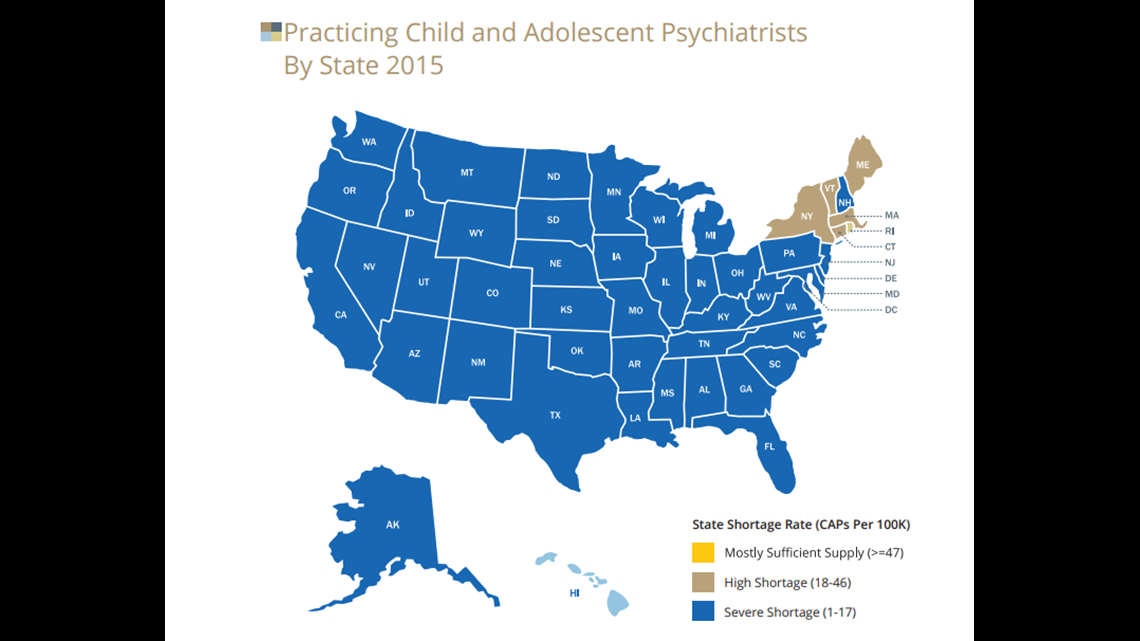

There aren’t nearly enough psychiatrists focused on children and adolescents anywhere in the U.S. The 'Psychiatric Shortage' study also shows 55 percent of states have a “serious shortage” of child and adolescent psychiatry.

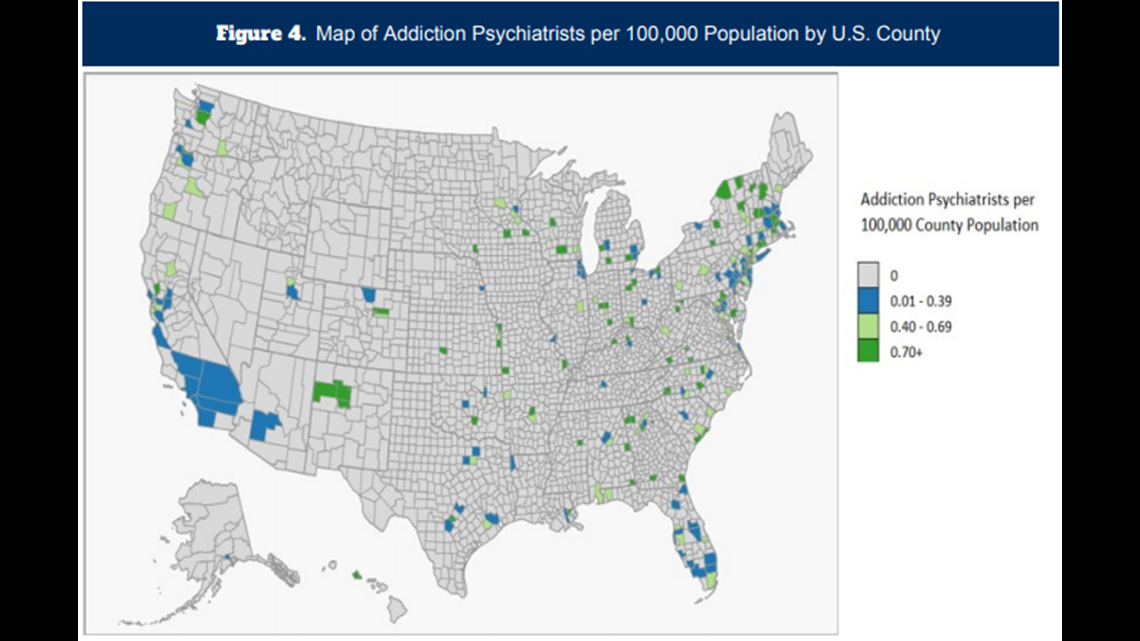

The color blue on this map represents a severe shortage.

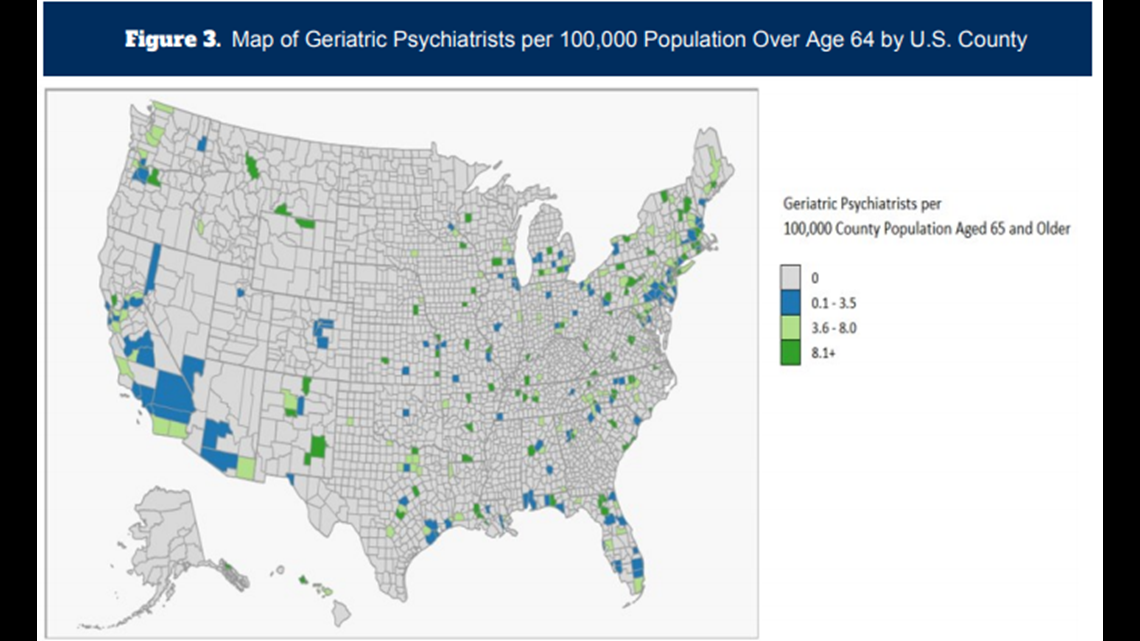

Even more harrowing is how few geriatric psychiatrists and addiction psychiatrists are practicing in the country.

The University of Michigan School of Public Health Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center published these maps: The gray areas show where there are zero psychiatrists specializing in those fields.

According to the 2018 Merritt Hawkins report, about 406 general psychiatrists are practicing in Oregon, which ends up being less than 10 psychiatrists per 100,000 people. In other words, that’s about two-and-a-half psychiatrists for all the people who could fill Providence Park in Portland.

“The shortage in Oregon pretty much reflects the shortage nationally,” said Dr. Danny Bristow, president of the Oregon Psychiatric Physicians Association.

Like the rest of rural America, Bristow says, rural Oregon is at a disadvantage. The majority of the population is concentrated in a couple areas of the state, while the rest is underserved.

“The stigma is decreasing at the same time the need is increasing, at the same time supply is dwindling fast,” Bristow said.

Why supply is dwindling

Supply is dwindling in part because psychiatrists are getting older; most are over 55 years old.

“We’re going to have a lot of people retiring and not nearly enough going into the field to meet that demand. And that’s scary,” Bristow said.

Low reimbursement from Medicare and Medicaid, and even private insurance, is also a factor. Historically reimbursements for psychiatric services have not been on par with other medical services, in part because of the stigma associated with psychiatric patients and care.

Bristow says there tends to be a bias against people with psychiatric illness and against those who care for them among medical colleagues.

Some providers can’t afford to keep their doors open with current insurance reimbursement rates. As a result, there are a number of psychiatrists who don’t offer services to patients with Medicare or Medicaid. In Oregon, Keepers said, it’s more than 50 percent of psychiatrists.

A trend is building in which many psychiatrists are now exclusively accepting cash in private practice. That creates an even bigger barrier to increasing access, specifically for people accessing services in community mental health centers and other publicly funded programs. According to this study, that is also detrimental for expanding collaborative care models in primary care settings.

Another cog in the wheel: Not many psychiatrists serve people with severe and persistent mental illness, who are typically the patients who utilize community health services.

This study shows there is a need for more psychiatrists. But there is no need for those who don’t serve that population, or who work in cash-only practices, refuse to take medicaid recipients, or don’t work with other medical providers to integrate treatment.

The pool of psychiatrists is also shrinking because of burnout, burdensome regulations and confidentiality restrictions.

The shortage isn’t necessarily due to lack of interest in the field, like it once was; Keepers sees it every year when sifting through applicants. However, there are still a small percentage of medical school graduates choosing to go into the field of psychiatry.

“There are actually more people who want to go in than there are residency positions available across the country,” Keepers said.

That’s because of limited federal and state funding for psychiatric medical residency slots. Bristow and Keepers say more residency positions need to open up to patch the gap.

But that’s not an easy solution by any means.

Long-distance psychiatry

The solution Bristow lives each day is a more attainable solution as technology improves and becomes more affordable. He’s a full time telepsychiatrist.

“All the work I do is via video conferencing from my office here,” he told KGW. “This is one of the ways we can start to meet the need for psychiatric care with folks who often don’t have very good access to it.”

Access is slowly expanding through collaboration between psychiatrists and primary care physicians, which is called a collaborative care model.

Ironically, the National Council Medical Director Institute study lays out how the psychiatrist shortage will only worsen and demand for services will only increase with the integration of the new models.

Keepers and Bristow know in order to attack the problem, the mental health care workforce as a whole needs to expand, not just the number of psychiatrists. Psychiatric nurse practitioners can and are helping shrink the shortage, as they can prescribe medication.

This article discusses how multi-clinician behavioral health teams - including nurse practitioners (NP), physician assistants (PA) and psychologists - are key to closing the gap between the demand for mental health treatment and the shortage of psychiatrists.

It’s not just one solution that’ll make a difference. But training more psychiatrists and mental health providers such as PA's and NP's, as well as recruiting incentivizing more to practice in rural, underserved areas, are key approaches.

“We can’t let the deficits of the health care system prevent people from coming for help. We have to keep trying,” Bristow added.

It takes a village

Experts say it’s on a variety of stakeholders to find new ways to help people who are suffering: providers, policymakers, federal and state governments, insurance companies, provider trade associations, advocates and health care administrators need to work together and in each of their spheres to take action and influence funding, regulation and delivery.

For American families like the Berrys, who are living it every day, the crisis is urgent.

“At the end of the day what I have really learned is that love is a powerful force. And there is nothing more frightening than the thought of losing your child as a parent,” said Kimberly Berry. "We have to start looking at mental health as potentially deadly."

The shortage is projected to worsen by 2025, especially in rural parts of the country.

Berry started a coaching service and podcast series for other families and individuals struggling with mental illness to help them navigate the world of behavioral health. Her site is called 'Being UnNormal'. She encourages anyone wanting to learn more or connect to others with lived experiences to reach out.