PORTLAND, Ore. — The city of Portland allocated $3 million in CARES Act funding to help bridge the digital divide by providing roughly 8,000 debit cards preloaded with $364 each to cover the cost of internet for one year.

A KGW investigation found the government program aimed at providing connectivity for low-income residents and people of color had structural flaws.

Smart City PDX had no system in place to determine whether funds were used for the intended purpose — a key measurement of the program’s success. Instead, the program relied on good faith that recipients would use the $364 cash cards on internet, instead of something else.

By contrast, similar projects elsewhere including Houston and a state-run program in Alabama provided vouchers for service providers, such as Comcast, to ensure that qualified applicants could stay connected to the internet.

“When you hand out a gift card that just has money on it or there’s not a voucher attached to it — there’s no guarantee that money will be spent on what you want it to be spent on,” warned Eric Fruits, vice president of research at Cascade Policy Institute.

Smart City PDX suggested that prepaid gift cards gave recipients greater freedom, privacy and convenience to set up new internet service or upgrade existing service.

“Internet assistance cards allow each individual to identify the best way for them to connect to the Internet,” explained the Smart City PDX website.

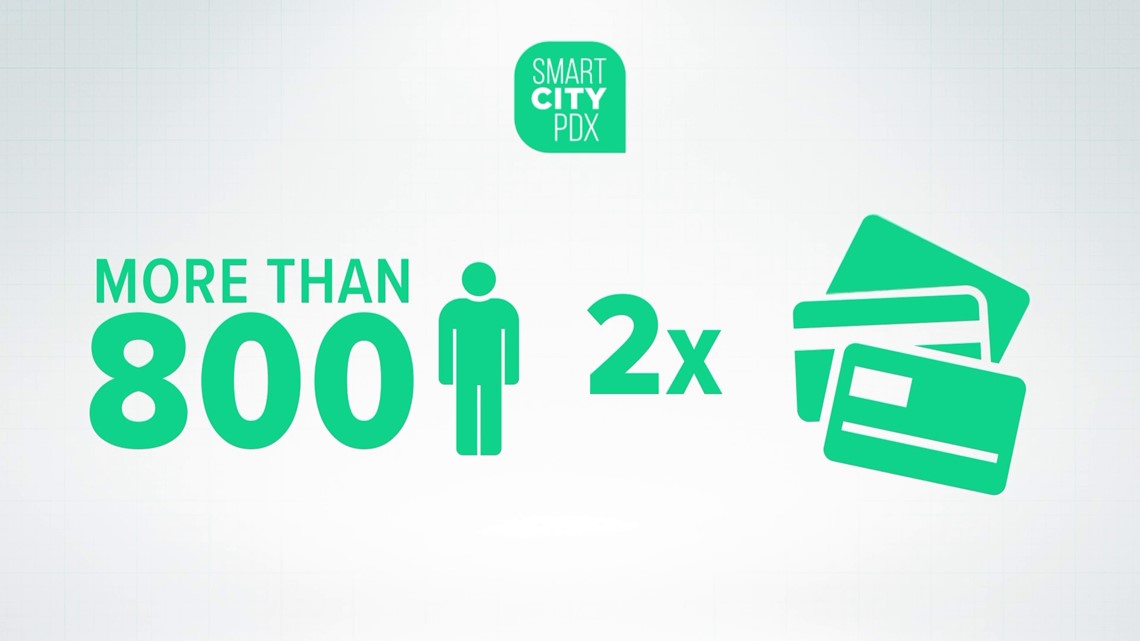

KGW’s analysis of Smart City PDX records obtained through a public records request found the program had unequal distribution. More than 800 people received two or more prepaid debit cards. One person took home six cash cards, valued at more than $2,000. Another person got five debit cards, despite listing only four people in their household.

Officials from Smart City PDX explained some recipients needed more costly high-speed internet due to the number of people in the home.

The uneven distribution of internet cards is a problem because most people who wanted one were left empty handed. Of the roughly 23,000 requests for internet assistance, only 36% of the requests were met.

Records also suggested 60 people who got cash cards were not eligible because they don’t live within Portland city limits, a requirement for the government program.

In July 2020, the city of Portland received $114 million in federal funds to help support residents facing extreme hardship from the coronavirus pandemic. City leaders dedicated $5 million of that CARES Act funding to help bridge the digital divide by providing reliable connectivity, computers and iPads to those who have limited access to the Internet or no access at all.

A 2018 survey found 32,000 households lacked internet service in Multnomah County and about half of those households didn’t have a computer.

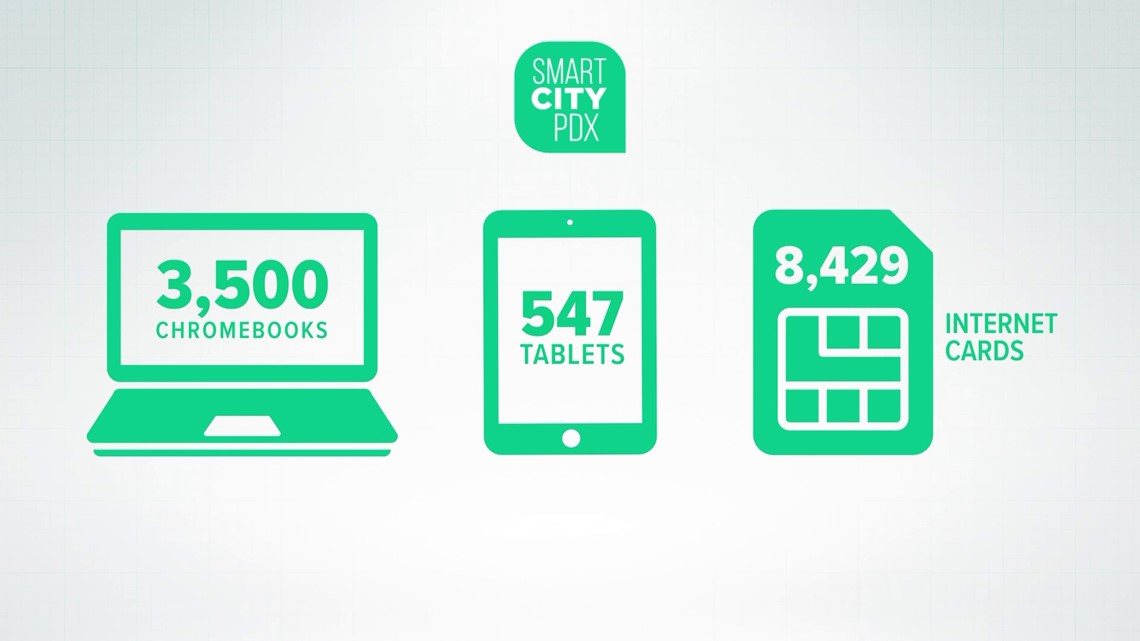

Portland’s Smart City PDX program led the effort to deliver 3,500 Chromebook computers, 547 iPads and 8,429 internet cards. Smart City PDX relied on two dozen community organizations that directly serve low-income Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIOPOC) communities, people with disabilities and seniors to help distribute the technology kits and pre-paid debit cards.

The largest share of the program’s $5 million in funding went to pay for internet access. The city spent $3 million in CARES Act money for U.S. Bank Rewards Visa cards, along with $12,000 in card fees and shipping.

Each pre-paid debit card was preloaded with $364.45. Recipients of the debit cards pledged to use the money to pay for internet service but were not required to submit their name, receipts or other documentation of how funds were used.

Program designers admit once the prepaid debit cards were distributed, there was no way to monitor if, where or how they were used. It was no different than handing out $364 in cash.

One critic questioned whether the program achieved its intended outcome.

“If the goal was just handing out gift cards then they achieved that goal. But if the goal was to provide increased internet access, then we have no way of knowing whether we achieved that,” said Fruits.

A similar program, PDX Assist, run by the Portland Housing Bureau also gave out prepaid Visa debit cards to households struggling during the pandemic. But the housing bureau used a different type of card. The U.S. Bank Expense card allowed the housing bureau to monitor point of sale purchases — where cards were used, but not what was purchased. Additionally, the housing bureau could track if cards were activated. This monitoring proved effective after thousands of cards were reported lost, stolen or missing.

WATCH: Thousands of pre-paid debit cards for COVID relief never arrived or were accidentally thrown out

Smart City PDX did require the 24 nonprofits distributing the debit cards collect anonymous data about each recipient including zip code, race/ethnicity, disability, gender, languages spoken, age and a breakdown of the number of people in the household.

Most recipients provided some or all demographic data requested, but 206 had no information listed beyond zip code.

A spreadsheet of demographic data provided by the city didn’t account for 115 cash cards. It’s not clear what happened to those debit cards or if they were distributed.

Staff with the Bureau of Planning and Sustainability and Office for Community Technology, which help make up Smart City PDX along with community members, faced a tight federal deadline of Dec. 30, 2020 to allocate CARES Act Grant funds.

In May, a city audit raised concerns about another program, Prosper Portland’s Small Business Relief Fund, which provided $12 million in emergency grants to Portland small business owners. Auditors found Portland interpreted eligibility criteria generously, didn’t have a reliable way to evaluate results and didn’t protect against misuse of funds in a rush to get relief money out during the pandemic.

KGW made multiple requests for an on-camera interview with the city of Portland.

Kevin Martin and Christine Kendrick, both from the Smart City PDX team, agreed to speak privately with a reporter but declined an on-the-record interview.

Public information officer Eden Dabbs, who is a spokesperson for the Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability also declined an interview.

The Smart City PDX website describes how CARES Act funding provided a critical lifeline during the pandemic for BIPOC communities and people with disabilities. The website also explains how the project was only able to fulfill about 25% of the need.

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased dependency on technology. Limited access to the internet makes it difficult to work from home, learn online, conduct virtual visits with a doctor, access resources or connect with family and friends.

As Portland looks to bridge the digital divide in the future and potentially allocate more funding, one critic argues it is important to be able to measure success.

“Did we actually help them?” said Fruits. “Good government is about the services delivered, not just the money that is being shoveled out the door.”