Oregon paid 288 state employees $3.2 million to stay home last year

An examination of public records found there are no limits on paid time off for those accused of workplace misconduct, often at a great cost to taxpayers.

The Oregon Department of Corrections paid Jaime Cook $98,388 last year to stay at home, watch Netflix and play World of Warcraft video games.

Cook is a registered nurse but hasn’t been to his job at a state prison since October 2018. He was on paid administrative leave for the past 16 months, waiting for the outcome of an internal investigation about his conduct on the job.

“This is the never-ending story of staying at home,” said Cook. “I don’t want to be here. I want to work.”

Instead of going to his work site at the Oregon State Correctional Institution, Cook is required to clock in from home Monday through Friday like a normal workday, including a lunch break. He can’t leave his house until his shift is over.

Cook earns his full salary, gets paid for holidays and accrues vacation time. He even got an annual cost of living pay raise while sitting at home.

“This is not supposed to happen,” explained Cook.

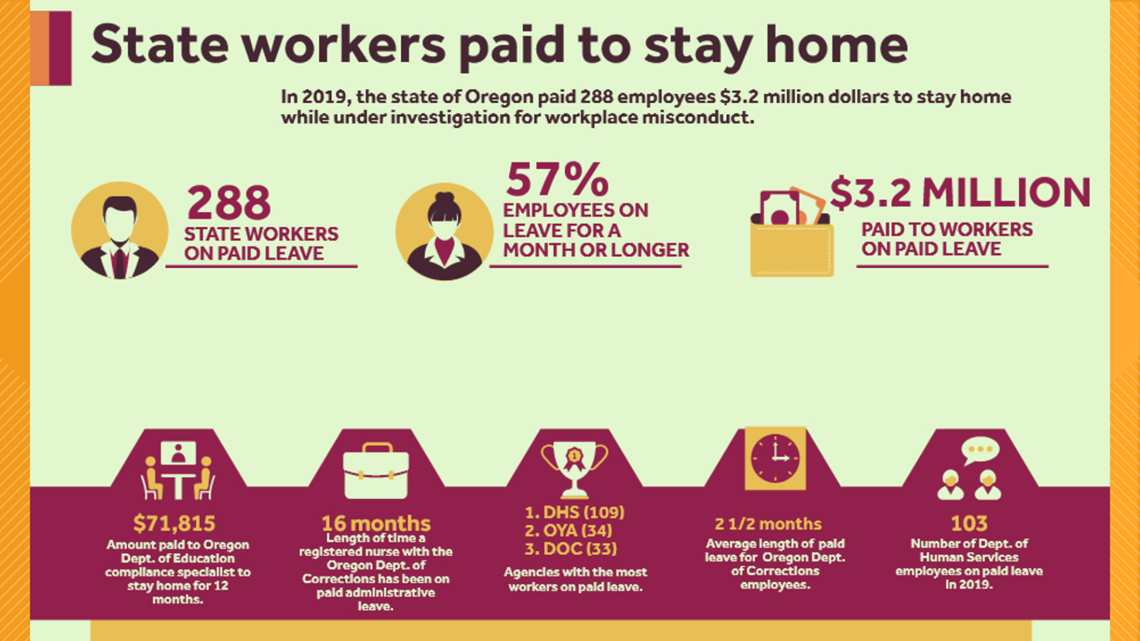

In 2019, the state of Oregon paid 288 employees $3.2 million to stay home, according to public records obtained by KGW. Of those, 164 state employees – or 57% – were on paid administrative leave for more than a month. Twenty-five state employees were paid to stay away from work for six months or longer.

“The number of these instances and in particular, the length of time, needs to be thoughtfully re-evaluated,” said David Kreisman of Oregon AFSCME Council 75, a union that represents 25,000 workers in Oregon.

State agencies large and small placed workers on paid administrative leave for long periods of time while alleged wrongdoing on the job was investigated, according to KGW’s analysis.

The Department of Human Services, the state’s largest agency with approximately 9,000 employees, had 109 workers on paid leave last year at a cost of $1.1 million. Sixty-nine percent of DHS personnel investigations dragged on for more than a month, according to public records.

“Due to the nature of the work of DHS, personnel investigations can be extremely complex and take quite a bit of time to conduct,” explained Jake Sunderland, spokesman for DHS.

The Oregon Department of Education had three employees on paid administrative leave last year, including one worker who stayed home all 12 months. The education compliance specialist, who was not identified by name in public records, was paid $72,000 to stay away from work on paid administrative leave. It’s not clear why the Department of Education employee was placed on leave or the current status of the workplace investigation.

Analysis of public records by KGW found the use of paid administrative leave by Oregon state agencies is costly and previously has not been reviewed extensively.

State agencies are not required to record or report employees’ on paid administrative leave. No one is tracking it and there are no state requirements setting limits on how long a worker can be forced to stay home while under investigation for misconduct or wrongdoing.

No end in sight

Jaime Cook spends weekdays at home on his computer playing video games or in front of the television.

“I do binge watching. I’ve got Netflix. I’ve got Amazon Prime,” explained Cook. He has watched the entire "Breaking Bad" series, watched "First Blood" and 14 seasons of "Supernatural."

He’s also learned to cook new dishes, plays pool and completed odd jobs around the house while on paid leave.

The Department of Corrections doesn’t allow Cook to leave his home until his shift is over, even though he has no work to do.

Cook admits that initially paid administrative leave felt like a paid vacation. But not anymore. He’s ready to go back to work. Cook misses his coworkers and feels bad that they’ve had to fill in during his absence. The registered nurse wants to be productive again and help patients.

“I’m not generally a depressed kind of person but this has tested me,” explained Cook.

The prison agency placed Cook on paid administrative leave, also known as “duty stationed at home,” on October 12, 2018. Records provided by Cook indicate he is under internal investigation for violating DOC policies, including code of conduct, code of ethics, promotion and maintenance of a respectful workplace, and abandonment of assignment.

Cook claims he did nothing wrong and deserves to keep his job.

KGW could not independently verify the allegations against Cook because DOC personnel files are confidential and the agency declined to comment on his case.

In 2019, the Oregon Department of Corrections paid 33 employees a combined $496,955 to stay home, according to public records. The average length of an investigation was two-and-a-half months.

A DOC human resources official explained personnel investigations are complex and take time. Witnesses must be interviewed, outside agencies or police might be involved and most employees have union representation. The agency also must consider safety risks.

“We have a responsibility to treat the employee fairly and to make sure that we are investigating appropriately and not missing anything,” said Gail Levario, assistant director of human resources for DOC.

Like most state agencies, DOC does not track or report paid administrative leave, making it difficult to tell if cases have increased or decreased.

The most recent publicly available data came from a Joint Ways and Means legislative subcommittee meeting in 2014.

Records show DOC director Colette Peters told lawmakers the agency had paid 59 employees $580,693 to stay home during 2013. Three of those 59 employees were out for more than 12 months.

“We believe the department’s use of administrative leave is appropriate,” director Peters explained to lawmakers in 2014 testimony.

Putting limits on paid leave

In Oregon, there are no statewide standards when it comes to placing employees on paid administrative leave.

The Department of Administrative Services provides guidance to help agencies conduct investigations but the decision whether to keep a worker at home is made on a case-by-case basis by the agency where the employee works.

There are no required timelines in state policy, although some collective bargaining agreements do address how quickly workplace investigations need to be completed when a worker is on paid administrative leave.

For example, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) representing 22,000 workers in state offices requires an investigation to be completed within 120 calendar days. If the investigation isn’t wrapped up by the deadline, the state agency will notify the union how much extra time is needed.

Several states and the federal government have limits on how long employees can be on paid administrative leave pending an investigation.

Connecticut limits paid leave to 15 days to investigate charges that could lead to dismissal. In some cases, paid leave can be extended to 60 days if criminal charges are pending and permission is granted by the Commissioner of Administrative Services.

In Washington paid administrative leave, also known as home assignment, can last up to fifteen days. The leave can be extended in 30-day increments, if approved by the agency head, who is required to receive updates.

In 2016, Congress passed the Administrative Leave Act, which was supposed to cap investigative leave to 10 days a year for employees and set up a procedure for agencies to grant additional leave, between 30-90 days, to complete personnel investigations. Two years later, federal agencies have been slow to implement the policy.

Lengthy periods of paid leave are not as common in the private sector.

“As a general rule, private employers tend to be stricter with their leave law entitlements for their employees,” explained Clarence Belnavis, a labor and employment attorney with Fisher Phillips in Portland. “They have an incentive to make sure folks get back to work when they are capable and able to return to work.”

The process shouldn't take so long

Jaime Cook recognizes there are legitimate reasons for keeping employees at home with pay pending a full and fair investigation. But he wonders if there should be limits on paid time off for those who had potentially committed misconduct or some other offense, often at a great cost to the government.

“This has probably cost the taxpayers $200,000 for just me to be off and I’m not the only person,” explained Cook.

After 16 months at home on paid administrative leave, he’s anxious for his case to be resolved. Cook hopes to return to work and use the skills he was trained for as a registered nurse.

“I went to school to save lives,” said Cook. “I didn’t go to school to play video games.”

Editor’s note: On February 20, the Oregon Department of Corrections notified Jaime Cook the agency had completed its 16-month internal investigation. Cook will return to work. He received a letter of reprimand. A DOC spokesperson could not explain the timing of the decision, which coincided with the release of KGW’s investigative report.