SURF PINES, Ore. — For seven years, Ken Weist and his wife have watched elk roam through their backyard in the gated Surf Pines neighborhood.

“They’re incredible, majestic creatures,” said Weist, who also works as the executive manager of Surf Pines, a community with more than 400 residents. “We know it’s not something you see everywhere.”

Herds of elk, accustomed to people, travel up and down the Oregon Coast, even passing through residential neighborhoods like Weist’s west of Highway 101.

Sara Gage, who lives just south of Surf Pines in Gearhart, recalled the time she saw a "parade" of dozens of elk in the dunes outside her window, or the time she watched one of them give birth near her home.

The elk, Gage said, are part of her community’s identity. But something changed in the last few years.

“Everybody noticed it and everybody in town was talking about, 'What happened to the elk?'” Gage said. “The herd was gone.”

Weist knows what happened. He said he sometimes awoke to the sound of gunshots near his home; over the space of two years, between 2021 and 2023, hunters shot 77 elk on a neighbor’s property.

“Watch a mother get shot and watch how the babies cry for three or four days, it’s heartbreaking at times,” Weist said. “There really hasn’t been anything concrete that I’ve heard that makes any sense about any of this.”

The elk hunting in Surf Pines was legal. It was sanctioned by the Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife as part of Oregon’s landowner damage tag program.

The state-managed program allows people to hunt elk on private property if the landowner shows property damage caused by the animals.

But where is the line? Is the compensation program being used appropriately to reduce conflict between elk and humans, or is it being abused?

From early 2021 to the spring of 2023, Surf Pines homeowners Craig and Dana Weston reported property damage to ODFW, ultimately receiving 80 tags for hunters to kill elk — 77 of which were used successfully, per ODFW.

Any person with a valid Oregon hunting license can use one damage tag per year, provided they have not already harvested an elk during the general or controlled hunting seasons.

KGW spoke with Craig Weston on the phone multiple times. He explained that elk had damaged fences and ate the feed for horses that they board on their property.

Weston declined an on-camera interview but said he’s not planning to apply for more damage tags — in part because of the backlash and threats that he’s received.

Some of Weston’s neighbors, including Jim Aalberg, Weist, and others that contacted KGW, have expressed their ire with the use of the damage tag program.

“(This was like shooting) big fish in a little barrel,” Aalberg said. “I struggle and I think others struggle to find out what damage there was to connotate the taking of this many animals.”

Weist, who lives as close as anyone to the property where the elk were shot, said he doesn’t think hunting in a neighborhood is a good thing.

“I mean, give the elk a chance, you know,” he said. “I’ve always felt it was kind of cheating — you see your herd of 100, you pick one, you shoot it … I just kind of feel that takes the sport out of hunting.”

Joe Surmeyer was one of the licensed hunters who shot an elk on the Weston’s property. He said he took a friend who likely wouldn’t have been able to hunt elsewhere and they took the elk meat home to eat, share or donate.

“It was a great experience for me because I got to take a 90-year-old guy out there, probably for his last (hunt), because after we were done he said, ‘This is my last one, I think that did it,'” Surmeyer said.

When asked to describe the need for the ODFW damage tag program, Surmeyer pointed to the changes in elk population and behavior that he’s seen over his lifetime.

“I’ve hunted elk here for 40 years, there are more in town now than there are up in the hills,” he said. “You can’t eradicate them, that’s not the point — the point is, you’ve got to suppress the herd, you’ve got to get it down low enough.”

Surmeyer explained that the hunting process was tightly controlled, with ODFW having designated three locations from which to safely take a shot and limitations on what hunters could shoot.

“They’re damaging fences on people’s property and he has horses out there so he’s liable, that’s a big part of it,” he said. “The other thing is, when you get these elk running across the highway — you get hit by an elk, it’ll be in your lap.”

On the northern Oregon Coast, the elk damage tag program stretches well beyond Surf Pines. KGW requested public records on the program — showing who’s using it, where, and for what reason.

From January 2021 through November 2023, ODFW issued 625 elk damage tags in Clatsop County alone. Hundreds of different hunters reported successfully killing elk, and 17 different landowners received at least a dozen tags over that stretch.

KGW talked on the phone with multiple other landowners who have used the program. One explained that he’s a farmer who lives near a wildlife refuge. Elk damage his crops, and therefore, his livelihood, so he requests a few tags each year as a deterrent and “it often works.”

Other landowners said they believe the program is a useful tool at managing the size of elk herds, as elk can quickly repopulate.

Ultimately, the responsibility for how the program is managed lies with ODFW.

Paul Atwood, a district wildlife biologist for ODFW based out of Tillamook, said he makes site visits to approve damages tags — looking for tracks, scat, and damage to fences and agriculture.

ODFW issues up to five elk damage tags to a property owner at one time, but there is no annual maximum.

Atwood said that after an initial site visit, a landowner may call and report that elk are still on the property or causing additional damage and ODFW may approve additional tags over the phone.

“It’s using (this program) as a tool to try and change elk behavior so they go somewhere else and aren’t in a position where they’re continually causing conflict,” he said.

When asked what damage ODFW saw to justify the approval of 80 tags in Surf Pines in just over two years, Atwood said that perspective relies on hindsight out of context.

“I don’t think there’s a magic number where this is what’s OK and this is what isn’t,” Atwood said. “I think you have to balance that with the size of the population and the amount of damage that’s being inflicted on the property.”

Atwood described coastal elk herds as tough to manage due to human development, adding that their low sources of mortality and "incredibly reproductive" nature are reasons ODFW could approve dozens of elk damage tags over a multi-year stretch.

“It’s pretty routine for us. (The Surf Pines approval) wasn’t out of the realm of other properties that have big conflict,” he said. “I think in this case the program was successful at changing elk behavior … if you move elk to a different spot and there’s not conflict there then that’s an overall win for both the landowner and the resource.”

Some community members have pushed back, saying that with this many tags, this elk herd wasn't moved elsewhere but killed off.

Other coastal residents have expressed concern over the concept of "trespass fees" — a way for landowners to charge hunters for the access to shoot elk on their property.

Elk meat is valuable and trespass fees could turn damage tags into a profitable business for landowners.

However, Weston said he never charged anyone. Every hunter that KGW talked to said they didn’t pay for access, and Atwood said ODFW would shut that down.

“The point of the program is to reduce damage and conflict on private land,” Atwood said, explaining why landowners aren’t allowed to sell tags to hunters. “It’s not, from my perspective, to allow a private landowner to make money off hunting.”

Atwood said if he heard of a trespass fee model, he would stop issuing tags to that landowner.

Despite the community backlash, Atwood said ODFW is running the elk damage tag program as the state legislature intended.

“The idea that elk populations are in trouble in Clatsop plains are just not true,” he said, adding that ODFW does turn down some requests for damage tags and that elk can be a threat to public safety.

Neighbors like Aalberg, however, don’t buy ODFW’s explanation and feel that the state has been too lenient in handing out tags.

“It does (feel like a culling), and I think it does to others too just because of the number (of tags) and relative size of the herd,” he said.

ODFW has downplayed the program’s impact on the "Gearhart herd" specifically, saying the department counted 149 elk in Gearhart in 2020 and that the hunting in Surf Pines harvested elk from three different coastal herds with 250 elk between them.

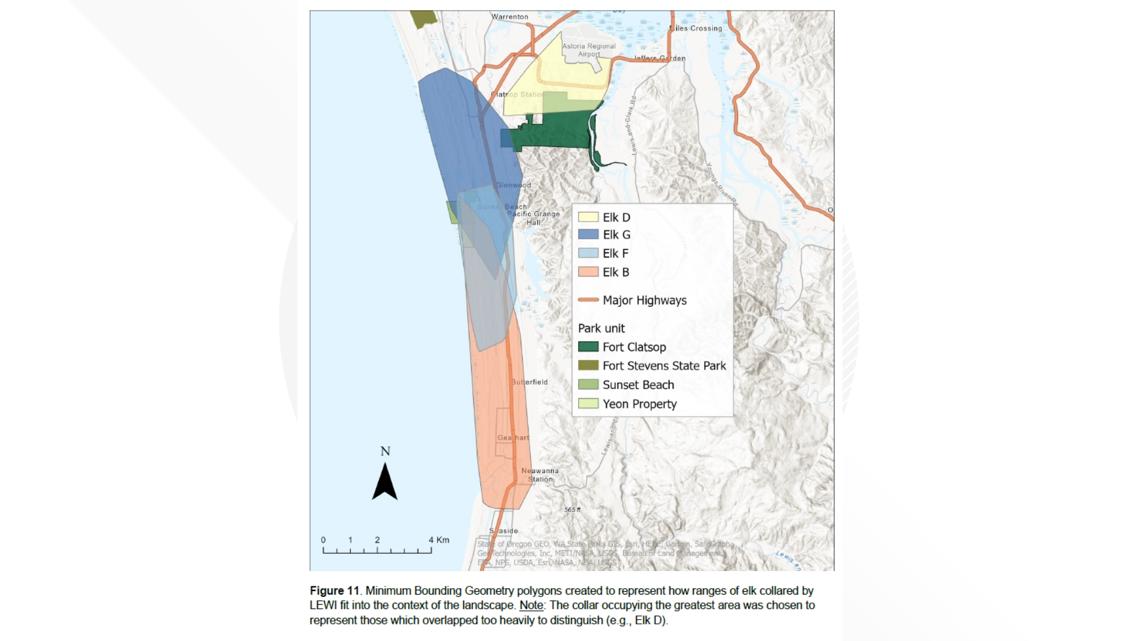

However, data from a National Park Service study that used GPS collars to track elk herd movement on the coast starting in 2019 could present a counter-argument.

The Elk B herd was the only herd to travel to Gearhart and cover land both north and south of the Surf Pines property. The range of the Elk F herd did come very close to the Surf Pines property at its southernmost point, but that elk herd was more often tracked to the north, near Sunset Beach.

After many community conversations, Gage said she believes the ODFW program may be more suitable to other properties, like ranches in eastern Oregon where elk damage cash crops.

She said a one-size-fits-all model across the state doesn’t work — with Surf Pines being an example of the program being used too broadly.

“In this case, it certainly was (used too broadly),” she said. “I think there are reasons, places where it’s appropriate. In this case it was just severe overkill.”

When KGW visited Surf Pines in January, there were elk on Weston’s property. Gage and others said they have yet to see elk return to Gearhart.

“Elk are not the property of ODFW or any individual owner of a parcel of land, they’re the citizens’ property, and in the future the state should be more transparent about what they’re doing,” Aalberg said.