Most Washington law enforcement agencies don’t use body or dash cameras, KING 5 investigation finds

Amid calls for police transparency and reform, dozens of leaders at Washington police agencies without body cameras say they're now actively considering them.

Survey of police leaders documents why WA body cameras are rare

More than 60% of Washington state law enforcement agencies have no camera systems to document police officers’ and sheriff's deputies’ interactions with the public, a KING 5 investigation found.

Dozens of police leaders, who participated in a KING 5 survey of nearly every law enforcement agency in the state, overwhelmingly stated that the long-term costs of managing, storing and releasing body-worn camera and dash camera video to the public had either prevented or discouraged their agencies from using the technology.

At three small Washington police departments that own the hardware, unused cameras are collecting dust because officials say they don’t want to incur the ongoing expense. A handful of other agencies that started dash or body camera programs opted to pull the plug after it became too costly and time consuming to manage.

But amid nationwide scrutiny of recent fatal police encounters and renewed calls for transparency following the May killing of George Floyd, just over half of the leaders at the 160 Washington law enforcement agencies without body cameras said they’re seeking funding, scoping out vendors or taking other steps to consider acquiring them. Many are bracing for the possibility that body cameras could be a major focus for lawmakers when the Washington state Legislature convenes again in January. In anticipation, one small-town police chief even turned to Amazon to buy the cameras himself.

Body cameras are self-contained, battery-operated cameras that officers attach to the front of their uniforms. They record interactions between police and the people they encounter on the job. Dash cameras are mounted on the top of a patrol car’s windshield and typically begin recording automatically when an officer turns on a siren.

For this investigation, KING 5 reporters interviewed representatives from 213 Washington state law enforcement agencies about the use of body-worn cameras and in-car video systems. The resulting database documents their responses and provides the most comprehensive examination available on the use of cameras across Washington state.

Currently, no state agency or organization tracks which departments use body-worn cameras or in-car video systems, according to the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs (WASPC).

(To enlarge the database, view in full-screen mode or click on the link above.)

KING 5's analysis of the 213 responses, collected between July 2 and Nov. 18, revealed:

75% of the agencies had no body cameras in use.

25% were using one or more body cameras.

79% did not use dash cameras.

21% had one or more dash cameras in operation.

63% had no camera system — no body cameras and no dash cameras — to record police interactions.

9% had at least one dash camera and at least one body camera in operation.

Five law enforcement agencies — in Winlock, Brewster, Newport, Colville and Winthrop — did not respond to any of reporters' questions. KING 5 did not survey the state’s 25 tribal police departments, which are sovereign governments and not required to respond to public records requests under the state law. At least 44 Washington municipalities that contract with another city or county for law enforcement services were not separately counted in the analysis.

(To enlarge the graphic, view in full-screen mode or click on the link above.)

While 53 police departments and sheriff's offices reported using at least one body camera, KING 5’s survey did not account for the specific number of body cameras or dash cameras in use at a law enforcement agency.

It’s unknown how often police interactions are documented on camera across the state, because in some cases, police departments that reported body cameras either did not require officers to wear them or did not own enough cameras to outfit most of their patrol officers or deputies.

Fatal police encounters lead some agencies to consider cameras

The number of police departments and sheriff’s offices with body cameras is a quickly evolving figure. Weeks after reporters initially contacted some law enforcement agencies, police or government officials had already made changes.

The Gig Harbor Police Department, for example, recently completed negotiations with its police union, and it plans to have its officers begin wearing body cameras by mid-December, according to Chief Kelly Busey. The Everett City Council approved a federal grant last week to help fund the majority of start-up costs for 150 body cams. At least two other law enforcement agencies — the Eastern Washington University Police Department and the Royal City Police Department — began using body cameras earlier this month.

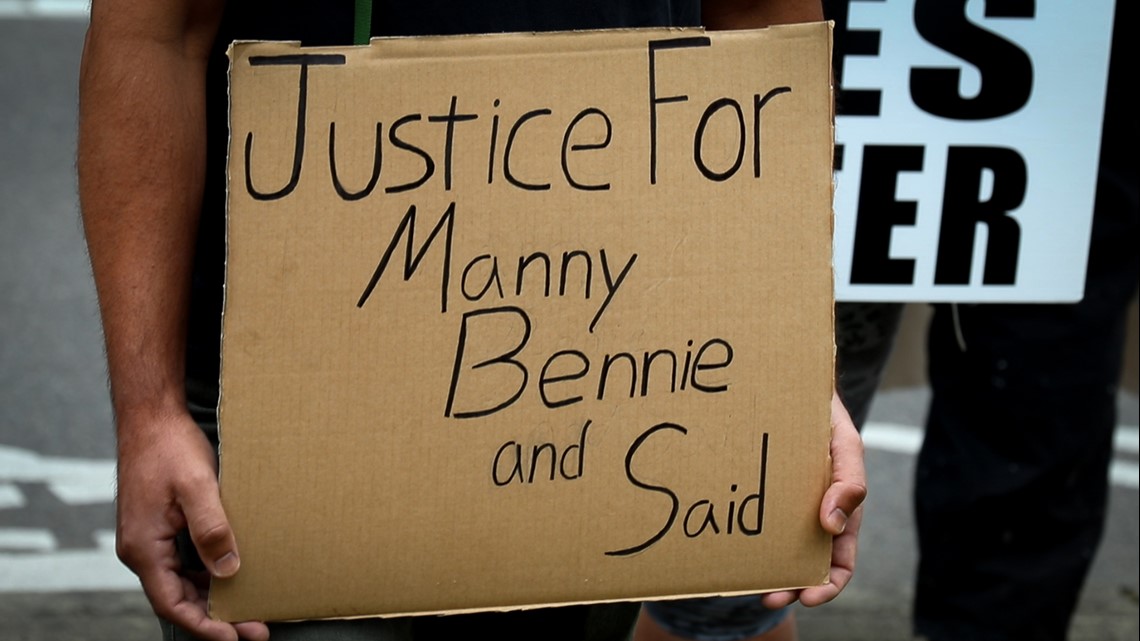

In some Washington communities where police encounters turned fatal, law enforcement agencies are considering cameras as a direct result of local protests and calls for reform.

Following the March death of 33-year-old Manuel Ellis, who died while being restrained by Tacoma police, city officials pledged to launch body cameras for all Tacoma officers by January 2021. Officers involved in Ellis’ death were not wearing body cameras and their vehicles were not equipped with dash cameras. Video shot on a cellphone contradicts police attorneys' claims that no one choked Ellis and that a taser was not used.

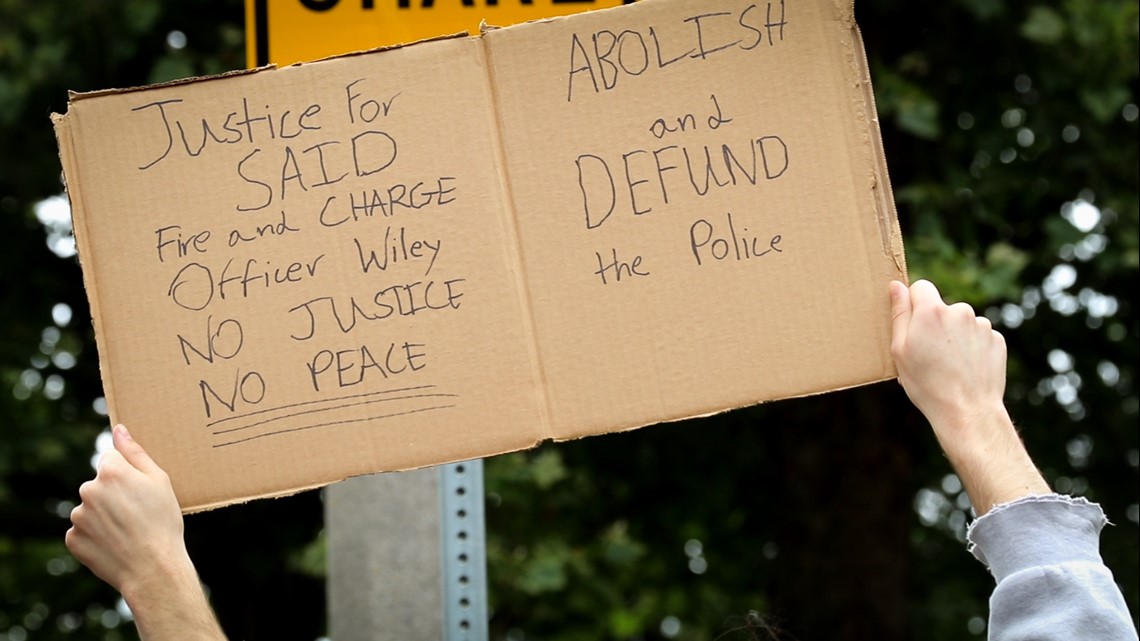

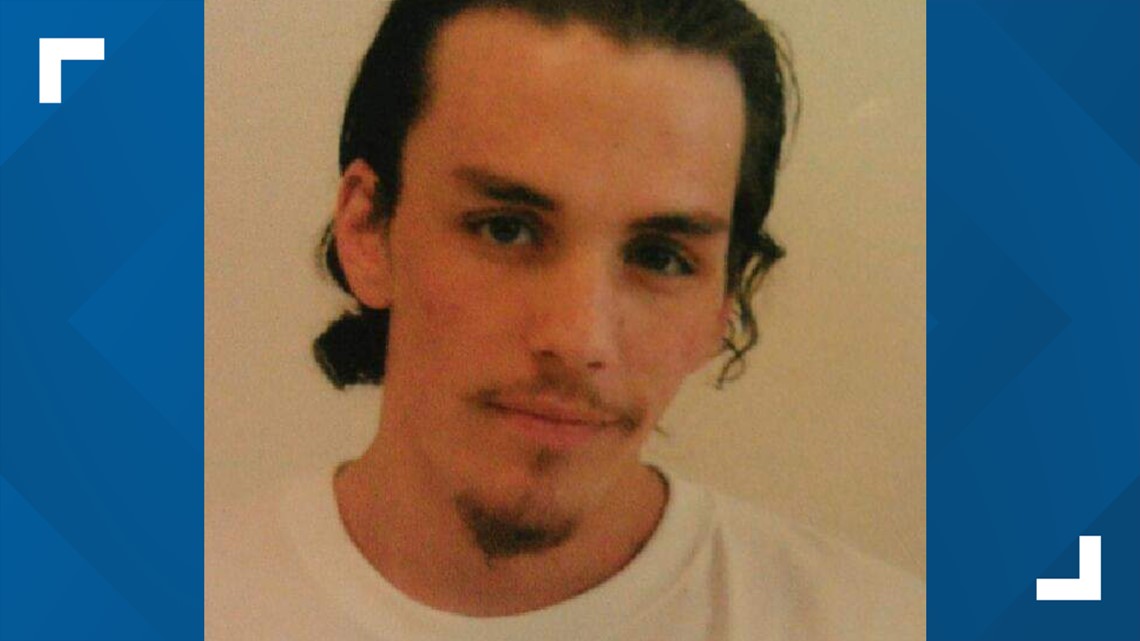

In nearby Lakewood, where Officer Mike Wiley shot and killed 26-year-old Said Joquin during a traffic stop in May, protesters have demanded body cameras for all patrol officers, in addition to other reforms.

In July, the police department, which is located in Pierce County, announced it was expanding the department’s dash camera program to outfit all its patrol vehicles. Lakewood Police Chief Mike Zaro said the agency, which has 98 sworn officers, currently has just two body cameras for its motorcycle officers. But he’s considering purchasing body cameras for patrol officers, too.

"We are evaluating the possible integration of body cams into our existing (in-car video) program so we would have both," he said. "That might be a year or two away, depending on funding and other priorities, but it’s something we are definitely considering."

Jorge Busso, whose brother Cameron Ayers was fatally shot by an East Wenatchee police officer in 2016, said having access to body camera video of his brother’s death would have made all the difference to his family.

“It could save everybody a lot of time, heartache and energy by just being able to watch a video and see who’s right, who’s wrong or at least get closure,” Busso said.

East Wenatchee Police Officer Kaiti Wilkins was not wearing a body camera when she shot 25-year-old Ayers three times in the back seat of a Chevy Cavalier, according to prosecutorial records. The officer said she shot Ayers that September day because his statements and movements were threatening.

Three months after the incident, the Douglas County prosecutor wrote that the shooting was not “clearly justifiable,” citing “conflicting information” and inconsistencies in the case. Wilkins was not criminally charged, but city leaders fired her after only months on the job and paid a cash settlement to Ayers’ father.

“When you’re left without any information, no evidence, no visual or audio, and you just allow your imagination to go wild with what little resources you have, it’s traumatizing,” Busso said.

At the time of the fatal shooting in 2016, body cameras were optional for East Wenatchee police officers, according to Chief Rick Johnson. As of this month, the department now requires all 21 officers to wear the cameras.

'Complaints are getting resolved really quickly'

Few of the police chiefs and sheriffs interviewed said they philosophically objected to the use of body cameras in law enforcement. In fact, many said they would prefer to have body camera programs to increase transparency, protect officers from false allegations and allow police leaders to more clearly determine what happened during an encounter.

“If my officers use excessive force, I need to know that right away, and the video helps me find that information sooner rather than later,” Kent Police Chief Rafael Padilla said.

Padilla’s department of 160 officers first strapped on body cams about a year ago. The Kent Police Department is still analyzing the data from the first year of the program. But, he added, there is anecdotal proof that the cameras have led to positive change.

“A lot of our initial complaints are getting resolved really quickly because of the video,” Padilla said. “We’ve been able to say, ‘Would you like to see the video?’ and then share that information and get to a deeper understanding about what really happened and why versus sometimes what was perceived.”

Padilla said the cameras have been an effective tool for department supervisors to know when they should take corrective action, like providing additional training for officers.

“We've had circumstances where we've learned, ‘Hey, we didn't do everything the right way,’” he said.

Some officers initially resisted Kent's transition to body cameras, Padilla said, because they weren’t prepared for the cultural shift of being recorded on camera throughout the course of their day.

“It took some adjustment,” he said. “But the reality is our officers really wanted these things.”

Kent Police Officer Chelsea Pribble also acknowledged that it was difficult for a few of her fellow cops to adapt. But she said she was excited and relieved when she found out she’d be wearing a body camera on the job.

She said her body camera is a helpful evidence tool as she works on cases, and it also gives her peace of mind that false accusations are less likely to stick.

“When a community member calls in, from a liability standpoint, it shows, ‘No, that’s not what I said,’ or ‘No, that’s not what I did.’ But I think it also shows positive interactions, too,” Pribble said. “I think people realized, after we all got them, how beneficial (they are) for us to have.”

At the Normandy Park Police Department, where body cameras are optional for the 10 officers who work there, officers were involved in two separate shootings — one with and the other without body camera footage. The recorded case was resolved much more quickly.

In June 2018, body camera video, reviewed by KING 5, captured the moment a Normandy Park officer shot a man in the shoulder during a suspicious vehicle stop. The cop fired his weapon after he saw the man holding a gun, which later turned out to be a replica.

About a year later, in July 2019, another shooting involved two Normandy Park officers. But unlike the 2018 case, those officers weren’t wearing body cameras.

Normandy Park Police Chief Dan Yourkoski said the King County Sheriff’s Office, which investigated both cases, had a more difficult time determining what happened in the 2019 case because of the absence of body camera footage. In turn, it took longer to clear the officers and release them back to duty, he said.

“The (body camera video in the 2018 case) allowed us to determine very quickly whether there was any criminal conduct by the officer. We determined that the officer had acted properly,” Yourkoski said. “If we didn’t have the body camera footage, it would have literally been the officer’s testimony. You wouldn’t have had that independent corroboration that the body camera provided.”

'It is strictly a financial burden'

Of the 160 law enforcement agencies that reported no body cameras in use, officials at 86% of the agencies—138 departments—cited financial barriers as at least one of the reasons why.

"We would love to have (body cameras) and our deputies are not opposed," Stevens County Sheriff Brad Manke said. "It is strictly a financial burden a low-income county cannot afford."

Like the Stevens County Sheriff’s Office, many agencies that say they can’t afford cameras are small in size. But two are among the state’s largest police agencies: the Washington State Patrol and the King County Sheriff’s Office.

Sgt. Darren Wright, public information officer at the Washington State Patrol, said 624 dash cameras are mounted in patrol cars, but the agency isn’t considering body-worn cameras for its 1,091 commissioned employees because the cost of the cameras is “prohibitive with current legislative funding.”

In a 2021-2022 budget request, King County Sheriff Mitzi Johanknecht asked county leaders for funding to launch body-worn camera and in-car video programs, according to media relations officer Sgt. Tim Meyer. To date, the county executive and King County Council have not agreed to fund her request. The sheriff’s office has 789 commissioned deputies, as of Nov. 5.

The Seattle Police Department, the law enforcement agency with the most police officers in the state, currently has about 950 of its 1,433 commissioned officers equipped with body cameras, according to SPD spokesman Sgt. Randy Huserik. The department spent approximately $5.9 million on the cameras between 2016 and 2019, he said.

Camera costs include more than equipment

The initial cost of the camera equipment isn’t the hold-up for many law enforcement agencies, according to KING 5’s survey. Officials at 61% of the departments that don’t have body cameras said they can’t afford them because of the workload from data management, including responding to public records requests for body camera video and blurring portions of video, like license plates and other private details that are exempt from release.

Yourkoski said he won’t require his Normandy Park officers to wear body cameras because his small administrative staff wouldn’t be able to keep up with an increased level of work.

“Personally, I prefer the cameras. I think that's the direction we’re ultimately headed in. For small agencies in particular, the challenge is going to be storage and managing data,” he said. “(In our case,) the weight of the potential public records requests kind of outweighed the benefit. But in the one particular incident where the officer did have a body cam, it was absolutely worth it.”

In Snohomish County, Arlington Police Department Chief Jonathan Ventura said his department, which doesn’t have body cameras or dash cameras, is discouraged by the long-term costs associated with body cameras.

"Despite claims the technology has never been more affordable, we find the contrary," he said. "Once the agency has committed to all the infrastructure and training to launch the program, the data storage fees and other software upgrade costs begin to (rise) out of control.”

(To enlarge the graphic, view in full-screen mode or click on the link above.)

Chief Michael Hepner, who runs the Bingen-White Salmon Police Department in Klickitat County said his department owns six body cameras—one for each of its officers. But they’ve never used the cameras because he says he would need to hire an additional person to manage the video and respond to public disclosure requests.

“I know it's not going to be in the budget to hire anyone else in the department this year,” Harper said.

The Kent Police Department, which is projected to spend about $800,000 per year on its body camera program, hired three additional people to help manage the video footage generated from its 125 body cameras. The city is funding the program using money generated from its red light camera tickets.

The Seattle Police Department spends about $1.1 million per year for hardware, software and storage, plus an additional $750,000 per year for six positions, Huserik said. Three of those people provide IT support for the camera hardware and software, and two review and redact the video. One person handles public disclosure requests—facilitating the release of video to the public and prosecutors, who use the footage as evidence in civil and criminal proceedings.

This year, to date, SPD has exported nearly 80,000 body camera files and more than 41,000 files from its in-car video systems, according to data provided by the police department. As of last week, staff had pulled 9,600 body-worn video recordings and 9,600 in-car video recordings that were requested through the public disclosure act, averaging about 200 requests per week. In addition to those public records requests, Huserik said, King County prosecutors made almost 12,000 requests for SPD body camera and dash camera video between January and October of this year.

'We need more police accountability, not less'

Dozens of officials at agencies without body cameras echoed Hepner’s concerns that they would need to hire additional staff to comply with state law. Some officials at departments that use body cameras or dash cameras complained of “frivolous and open-ended requests” filed by media outlets and activists, which, they say, “overwhelmed“ and “paralyzed” the agencies working to respond.

A number of sheriffs and police chiefs said they’re holding out hope that the Washington state Legislature will make revisions to the state’s public records act to make it less time-consuming and costly for departments to comply with requests for video footage.

“(We want to) work with the legislature to do all we can do to remove the impingement of the storage and management costs for those agencies moving forward,” Steve Strachan, executive director of the Washington Association of Sheriffs & Police Chiefs (WASPC), said. “The place we’d like to be is that if a department says, ‘We’d like to implement body cameras,’ if the cost is prohibitive, then the legislature would consider providing financial assistance.”

Without legislative changes to the Washington public records law or additional funding allocated by the state, some police leaders said they won’t bother looking into acquiring the technology.

"We are waiting to see what the legislature does with the rules related to storage and public disclosure," said Acting Fircrest Police Chief Victor Celis. "We are definitely interested in obtaining body cameras."

Local First Amendment advocates said they don’t support proposals to revise the Washington State Public Records Act in order to minimize the workload and financial burden for law enforcement agencies. The president of the Washington Coalition of Open Government (WACOG), a government accountability group that has not taken a position on whether police agencies should have cameras, said police video recordings should remain accessible to journalists and the public.

“Our main concern is that if the recordings are made…they should be available to the public or the news media,” WACOG President Toby Nixon said. “What we don’t want to see are any modifications made to the law that simply reduce access in the name of reducing costs.”

Kathy George, a WACOG board member and a public records lawyer who represents news agencies across the Puget Sound, said proposed revisions to the public records act could have a damaging impact on public trust.

“This is really a wrong time to be reducing public oversight of police conduct. I mean, just look at all the protests around the country in the wake of fatalities from police interactions,” George said. “We need more police accountability, not less. That’s the whole purpose of body cameras is to reassure the public that police are acting appropriately. It’s in the public interest to have access to those records.”

George acknowledged that managing body-worn camera and dash camera programs can be a “resource-intensive process” for police agencies. She, too, says it’s up to the legislature to support them.

“The answer is for the state to step up and provide the resources that police agencies need in order to build that public confidence that police officers are acting appropriately,” she said.

Some chiefs, sheriffs brace for statewide camera mandate

A significant number of police chiefs and sheriffs who responded to KING 5’s survey said they expected the state of Washington to eventually require police agencies to use body cameras. At least four states—Connecticut, Nevada, South Carolina, and California—have enacted laws that require some officers and deputies to use body-worn cameras, according to 2018 data from the National Conference of State Legislatures, which maintains a database of body camera laws across the country.

Strachan, the executive director of WASPC, said his association wants the legislature to fund body cameras for departments that want them, but he thinks it’s important that the issue remains a local decision.

“If there was a blanket mandate that (cameras) must be implemented, I think the concept is fine. But the problem is that you would, without a doubt, have departments that would be having to choose between staff and cameras," he said. “It’s just a matter of resources, and for those communities that don’t have the resources, they would be required to incur potentially tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs.”

In Roy, a Pierce County city with a population of 823 people, Police Chief Darwin Armitage has made it his mission to implement body cameras, even on a lean budget.

As unrest and calls for police reform in big cities grew over the summer, Armitage also began to expect that the state would soon require police departments to use body cameras. So, in August, he went shopping online.

“Seeing the writing on the wall, I figured...I better take that step real quick before things get too expensive and unavailable,” he said.

The chief, who patrols the city along with one other full-time sworn officer, turned to Amazon and purchased four body cameras that cost less than $200 each—a steal compared to the $6,000 bid he got from a major manufacturer.

“I could get a camera and the platform and everything else for far less than buying from these big people, these big guys,” he said.

Initially, Armitage paid for the cameras himself, before getting city leaders on board. On Nov. 23, Roy City Council approved Armitage's bottom-dollar police cameras. They’re expected to hit the streets before the end of the year.

“We're trying to capture everything that's happening right there in front of us so that anybody who's watching the video can place themselves in our boots or our shoes and see exactly what it was that we saw,” he said.

'Body cameras are not absolute in their value'

KING 5’s survey found a small number of police chiefs and sheriffs who either said they don't support body cameras or the police guilds representing their officers and deputies don’t want them.

Mercer Island Police Chief Ed Holmes said he isn’t opposed to body cameras, but he also isn’t interested in acquiring them for his suburban department. He said he doesn't believe that adding body cameras is the answer to increasing accountability or building public trust.

“I’m not sure that body cameras solve a whole lot of anything,” Holmes said. “I mean, when people look at the footage, you have people interpreting what’s happening differently.”

At the Walla Walla Police Department, Chief Scott Bieber has historically opposed the use of body cameras, according to public information officer Sgt. Eric Knudson. At a local government summit several years ago, the chief questioned the usefulness of the cameras and called them "one-dimensional," explaining that "too much importance is given to a small piece of the contact."

“Should a 5-second video clip, selected and run continuously by the media, define our department?” Bieber said.

Mount Vernon Police Chief Chris Cammock said he thinks the public distribution of body camera video can actually “erode” public trust.

“Body cameras are good evidence, but they aren’t absolute in their value,” Cammock said. “Other agencies have expressed frustration with video requests that lead to uploads on proprietary sites intending an entertainment value. These can be used in a less flattering light, which further erode instead of reinforce a confidence the public should have in police.”

Police guilds representing officers at the Ridgefield Police Department in Clark County, Cowlitz County Sheriff's Office, Marysville Police Department and several other agencies have objected to the cameras, according to representatives from those departments.

Still, most officials who responded to KING 5’s survey were hopeful that body cameras would serve as an important tool for restoring public trust at a time when relationships between police officers and the public are severely fractured.

“When everything first happened (after George Floyd was killed), you’re coming into work and you’re being flipped off and you’re being screamed at, and it’s difficult,” Kent Police Officer Pribble said. “I just came out and removed three children from an extremely, neglectful, abusive thing and then someone is telling me what an awful person I am.”

“You just wanted to be trusted...I want to do good, and I want to be good,” Pribble added. “I got to stay positive and hopeful that there will be something that comes along. But you also have to continue to get out in the community and show (that we should be trusted).”