Foster teen’s violent attack of Washington social worker highlights lack of safety solutions

As DCYF looks for a long-term solution to serve high-needs children, workers say the agency fails to find even short-term solutions to keep them safe.

A brutal attack

PUYALLUP, WASH - The Pierce County 911 operator who picked up the phone could hardly hear over the piercing screams of a Washington social worker in the background, pleading for her life.

“Help!” the social worker shrieked.

Deidra Van Every, who for months was tasked with protecting a 16-year-old male foster child, now cried out for protection from the same teenager. On that November evening last year, the teen dragged Van Every by her hair across a third-floor Puyallup hotel room – kicking her, stomping on her face and promising to kill her, according to law enforcement and court records.

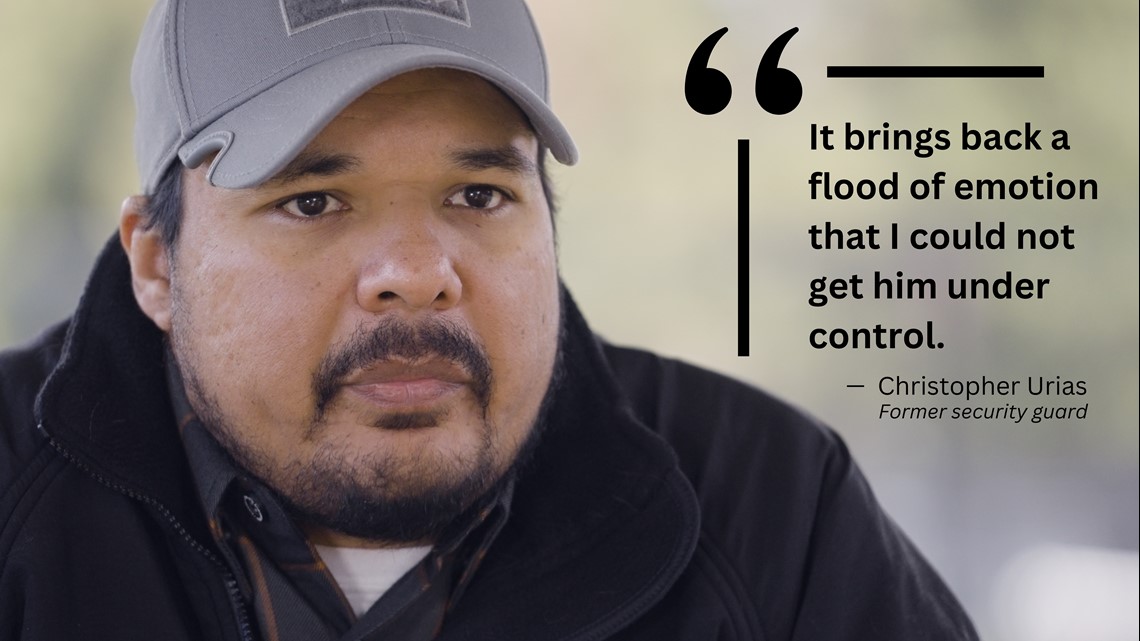

“She was begging him at one point – trying to appeal to his sense of humanity,” said Chris Urias, a former state-contracted security guard, who Van Every credited with keeping her alive. “There was a look in his eyes that he just wasn’t there.”

Van Every, a Pierce County-based supervisor in the Department of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) adoption unit, suffered a broken nose and a concussion from the brutal beating. Urias and the teen’s state-assigned therapist, who called 911, witnessed the attack.

“It brings back a flood of emotion that I could not get him under control,” said Urias, who attempted to restrain the teen before law enforcement arrived. “He was 16 years old, but the sheer size and power that he had is just humbling to say the least.”

Van Every’s assault is one of at least 38 incidents since September 2021 where Washington foster youth physically attacked child welfare workers, according to a Feb. 16 report from the Washington State Family and Children’s Ombuds. The ombuds’ data reveals most of those assaults occurred at hotels, where DCYF has historically housed hundreds of high-needs kids without foster home placements — including the 16-year-old who police said was responsible for the attack on Van Every.

“The majority of these assaults involve youth that are experiencing these unstable placement situations, where their treatment and behavioral needs are not being met,” said Patrick Dowd, the director of the ombuds’ office. “They’re probably angry. They’re probably frustrated – maybe even frightened.”

The teenager accused of assaulting Van Every is developmentally delayed and has multiple mental and behavioral health diagnoses that require 24/7 supervision, according to Pierce County court and law enforcement records.

Van Every – who publicly spoke of her assault in front of the DCYF oversight board last year – was one of a number of state social workers taking shifts to monitor the teenager while he stayed overnight in a hotel. With her camera off, she told board members over Zoom how the state was placing its social workers and foster children in jeopardy.

"I wish you could see my face right now because my face is the poster child for the retention issue that DCYF social workers are facing every day. Every day is a dangerous time and a dangerous place," she said at the November meeting held days after her assault. “This particular youth has not had placement since March in a substantive and meaningful way. He's had over 100 placements – most of them hotel stays – this year alone."

KING 5 is not identifying the teen because he is a juvenile. A Pierce County public defender who represented the teenager in recent court cases did not respond to a request for comment.

Van Every declined an interview. As she recovers from her physical injuries and emotional ones, her family members have vocally advocated for more protections for social workers on her behalf — speaking with reporters and testifying in front of state lawmakers in Olympia.

In the months before Van Every’s assault, court records reveal that DCYF knew the teen posed a threat to its staff. He was accused of physically assaulting at least four other state workers and regularly threatening the lives of others involved in his care.

Instead of beefing up safety protocols in response to his escalating and extreme behaviors, Urias said the child welfare agency opted to reduce the number of security guards assigned to the teenager’s case – from two guards to one.

“They said they were paying too much money for security, but at what point do you put a price on your employees’ lives? At what point do you put a price on safety?” Urias, the security guard, said. “If he was that high-profile, that high-risk of a child, that should never have happened in the first place.”

Jason Wettstein, a spokesperson for DCYF, declined an interview and did not respond to questions about whether the department reduced security in the teen’s case.

He explained in a statement that while DCYF can’t comment on cases involving specific children, the department makes decisions about security staffing by conducting “case-by-case assessments” that consider a foster child previous response to security guards and de-escalation strategies.

“Security changes and training in de-escalation can only go so far when youth with profoundly complex challenges do not have access to the services that would come with placement,” Wettstein wrote, calling out the state’s “urgent, unmet need” for housing options that can support high-needs foster children.

“(The youth) need habilitative mental health services – facilities with built-in safety measures, like furniture attached to floors, environments free of potentially dangerous items, etc. Currently, the state does not have these facilities for adolescents.”

‘This sounds like somebody else’s issue’

Throughout his teenage years in the child welfare system, records show the 16-year-old accused of assaulting Van Every has experienced consistent instability and chaos.

According to a review of his juvenile court cases, police reports and video obtained from law enforcement, the teen was repeatedly ousted from foster homes, group homes and residential treatment facilities as a result of his violent outbursts. Police and child welfare workers said the 16-year-old destroyed thousands of dollars worth of property, injured people and made threats against the lives of others and himself.

Despite his complex needs, institutions equipped to provide crucial treatment and support for the teenager outside of the child welfare system repeatedly turned him away, according to a review of Pierce County court records, including a September 2022 Joel’s Law petition that DCYF submitted to the court.

In some instances, law enforcement agencies declined to arrest the teen when the child welfare agency reported him for crimes. Hospitals declined to admit him following suicidal threats. Courts and mental health professionals declined DCYF’s requests to get him help through involuntary treatment. And judges dismissed the majority of his 12 criminal cases, as they repeatedly found the boy incompetent to stand trial.

“All the systems involved say, ‘This sounds like somebody else’s issue. It doesn’t sound like it’s for us,’” said one Seattle-based DCYF social worker, who has advocated for increased protections for workers and spoke on the condition of anonymity. “The responsibility gets passed around while we are babysitting these high-needs kids who we are not equipped to deal with.”

It is a reality that has left DCYF leaders desperately searching for a long-term solution to serve hard-to-place children, while failing to find even short-term solutions to keep their workers safe.

“It’s a huge problem,” said Mike Yestramski, president of the Washington Federation of State Employees, a union that represents about 2,000 state social workers.

'They're just trying to tread water and not get hurt'

That “problem” of social worker safety risks is by no means a new one.

In 2021, the multi-part KING 5 investigation “After Hours: Fostering Chaos” documented the chaotic and unstable environment for the social workers who are left alone on the night shift to handle some of the most challenging kids in the state’s care. Current and former child welfare workers who spoke with KING 5 reporters for the series described how on-the-job threats and assaults were common. They explained they lacked the tools and de-escalation training to diffuse those bad situations, and they didn’t feel equipped to safely perform their jobs.

In response, DCYF Secretary Ross Hunter pledged swift action to create safer working conditions for the social workers thrust into those difficult roles. He said DCYF would need to designate and provide “quick response staff,” who are skilled at de-escalating dangerous situations.

But nearly two years since Hunter publicly made those remarks, social workers said they are still grappling with the same safety-related challenges. Aside from the occasional security guard assigned to protect them from the most high-risk youth, “quick-response staff,” they said, are nowhere to be found.

“Social workers went into this field to help children – to make a difference with children, and that is not what they're doing anymore,” said Shelley Clark, a former Vancouver-based DCYF supervisor who said, in 2019, a foster teen tried to torch her with a lighter and aerosol can. “They're just trying to tread water and not get hurt, and it’s happening all the time.”

The recent state ombuds’ report on social worker assaults shows that at least four assault incidents took place while workers were transporting foster youth in their vehicles, and another one occurred in a parking lot while the child waited for transportation.

Wettstein, the DCYF spokesperson, explained that the department is considering adding Plexiglas barriers to state cars to better protect staff members from on-the-road attacks.

DCYF reports it is also in talks with security companies to find ways to “strengthen” agreements that provide for security guards, like Urias, to help look after the department’s most behaviorally challenging youth.

Wettstein claims that the agency has already taken other steps that immediately make working conditions safer, including leasing two facilities to supervise youth who are awaiting placement, which provide “greater environmental control for the safety of youth and staff.”

He said the department is offering additional de-escalation training for child protection workers at some DCYF facilities, maintaining files with safety information on youth who could pose dangers to themselves or staff, and reemphasizing that DCYF social workers should involve police if things get out of hand.

“We have made changes and adapted over time, but adaptation to a lack of adequate facilities and services for youth with the most complex needs can only go so far,” Wettstein wrote. “The fact remains, the state does not yet have the needed residential placements for adolescents with the most complex needs. Youth and staff will continue to be at risk until sufficient therapeutic placement and services exist.”

Assaults on workers 'woefully underreported'

DCYF has a “long-standing” policy that requires social workers to report assaults “so both staff and youth can gain help,” according to Wettstein.

Earlier this year, agency leaders reminded child welfare workers about DCYF’s protocol and the resources available to them in the aftermath of an assault. In an internal statewide email obtained by KING 5, a DCYF manager informed workers that they are entitled to “assault benefits,” which include support from peers and access to therapy sessions.

But despite the recent official communication, multiple current and former social workers said the agency’s real-world directives in the field haven't always been as clear.

A former afterhours social worker, who now works the day shift at DCYF, said her bosses didn’t offer any support after an 8-year-old foster girl she was supervising bit her arm, drew blood and left a scar.

“I was surprised by the people who were supposed to be in charge and their lack of response,” said the Seattle-based social worker, who requested not to be identified because she isn’t authorized to speak to the media. “What was most concerning was that my supervisors didn’t know what we were supposed to do and if it was supposed to get documented.”

Multiple state employees said the state ombuds’ count of at least 38 attacks on DCYF workers in the last 16 months doesn’t accurately reflect the scope of the problem.

“The assault numbers are woefully underreported,” said Yestramski, the union president.

Some child protection workers said they have felt discouraged from reporting physical attacks by youth in their care – especially when the incidents don’t require medical attention.

“There’s no official notice saying, ‘don’t report,’ but there is a culture of retaliation that is very real,” Yestramski said. “That has a chilling effect on people's willingness and ability to speak up and stand up against all of these things that we're seeing that everyone knows is wrong.”

In other cases, workers said they are sometimes reluctant to come forward because they worry that pursuing criminal charges against a troubled foster child might negatively affect the youth’s life or impact their own ability to safely work with them in the future.

'We need your help'

In the months leading up to Van Every’s assault last November, the state documented in police and court records that the 16-year-old had a history of assaulting multiple Washington child protection workers.

In July 2022, he allegedly “struck” a male social worker “at least twice” while the worker was preparing to transport him in a car, according to a Pierce County court case that was later dismissed after a judge ruled the teen was not competent to stand trial.

In August 2022, the teen allegedly threatened a different social worker with scissors and threw rocks at another DCYF employee, according to a petition DCYF workers filed in a Pierce County court last year. The state told the court that while law enforcement responded, police took no action.

In September 2022, Van Every and another social worker were picking up the teen from a Pierce County juvenile detention center when she witnessed the teen “kick,” “push” and punch” a social worker on her team, according to Van Every’s account of the incident in court records. Surveillance video also captured the boy destroying thousands of dollars worth of property and setting off a fire extinguisher inside the detention center.

The social worker assigned to the teen's case sought an anti-harassment order the next day in Pierce County Superior Court – fearing the teen who she said “kicked” and “punched” her.

Court records show that while the teen was arrested and placed back in detention after the September incident, he was swiftly released back to child welfare workers. A mental health professional with the authority to decide whether he qualifies for involuntary mental health treatment said he didn’t meet requirements.

Two months later – the morning after Van Every’s hotel assault – she learned that the teen allegedly responsible for her physical and emotional injuries was again deemed incompetent to stand trial. A Pierce County judge dismissed the entire case, which brought charges of fourth-degree assault and felony harassment.

The next day, the child welfare agency scrambled.

“We need your help,” a senior manager wrote in a Nov. 16 email obtained by KING 5 and sent to DCYF workers in the Pierce County region. “It is with great regret, the youth in question that assaulted our staff will be coming out of detention today.”

The manager asked for volunteers to help supervise the teen in yet another hotel – this time with the promise of three security guards.

Three months later, it’s now unclear if the department ever found an appropriate placement for the teen.

Becoming a foster parent

If you’re interested in becoming a Washington state foster parent, here’s how to contact the Department of Children, Youth, and Families to get more information about next steps.

Contact the reporters

Taylor Mirfendereski is a KING 5 investigative reporter, who specializes in multimedia storytelling, longform reporting and digital projects. Follow her on twitter at @taylormirf. E-mail her at tmirfendereski@king5.com or contact her via Signal at 206-348-4106.

Chris Ingalls is a KING 5 investigative reporter. Follow him on twitter @CJIngalls. E-mail him at cingalls@king5.com or contact him via Signal at 971-267-5320.

Watch: KING 5 investigations