Uncommitted: How high standards are fueling a cycle that can fail people with serious mental illness

Most severely mentally ill people don't meet civil commitment standards, but many struggle on their own. What's left is a mental health system with frustrating gaps.

Brenda Gardner started to notice changes in her son Eric's behavior during his senior year of college.

Eric did, too.

He told his parents he thought he needed brain surgery, so the Gardners picked him up from college and brought him home to see what was wrong.

Within months, Eric started showing escalating symptoms of a severe mental illness: chronic psychosis, delusions and violent thoughts.

"One day, he came downstairs screaming at me, spittle shooting out of his mouth," his mother Brenda Gardner said. "We had never seen anything like that before and that kind of volatile behavior just continued, it became much worse over time."

After violent threats, a booking in jail, a release, a no-contact order and a suicide scare, eventually mental health evaluators placed Eric on a hold — taking him to a hospital against his will for a medical assessment.

A doctor determined his mental illness was creating a danger to himself or others.

Following two weeks of treatment and care in a medical facility, Eric was released as his symptoms "stabilized," his mother said.

However, his chronic psychosis quickly returned and he stopped taking medication.

Family members tried to help and Eric lived with his parents for years, but he's now homeless.

"It just can't last, at some point it crumbles," Brenda Gardner said. "It's not Eric's fault. What I say is he's the victim, we're just collateral damage."

Eric Gardner was caught in a gray area. He wasn’t judged to be dangerous enough to warrant detention and forced treatment — what's known as civil commitment — but his symptoms worsened on his own.

His parents said housing was a constant concern and they lacked options for help.

Eric’s story is one example of how the current mental health system can fail to help people with severe mental illness.

High standards for civil commitment in both Oregon and Washington are creating a cycle in which most people don't reach requirements for involuntary treatment and care, but many aren't able to care for themselves once released.

Whether through a lack of resources, housing, workers, follow-up care or the current laws and standards themselves, KGW explores the gaps in our mental health system and how our entire community is suffering for it.

Civil Commitment: A last resort? 'Folks do not feel what's going on in our community is acceptable'

Civil commitment involves admitting a person to a medical or mental health institution against their will, where they often receive involuntary treatment and are prevented from leaving.

A commitment ends when a person is assessed and cleared by an evaluator or when the maximum treatment time has been served — up to 180 days in Oregon.

"The idea is that if you're experiencing severe symptoms of your mental illness, then your judgment, behavior and understanding about what you need to do is impaired," said Kathy Shumate, program supervisor of a Multnomah County behavioral health team. "Were it not impaired, you might make different choices."

For a person with mental illness, medical and mental health experts are quick to point out that civil commitment is a last resort.

"Taking away someone's liberty is normally something that's only done in the criminal justice system, so we only want to do it when there's no other way to keep them [and the community] safe," said KC Lewis, managing attorney for the Mental Health Rights Project, a team within Disability Rights Oregon.

The first segment of Uncommitted —The System at Work — aired Monday, August 29.

Very few people end up receiving a judge's order for civil commitment.

More often, a person demonstrating severe symptoms of a mental illness is placed on an initial mental health hold, starting an intricate and complex process of reviews to decide if that hold is, in fact, justified.

"The question is not whether or not a person needs treatment — they often do — but whether or not that person should be forced to get it," Shumate said.

Both Oregon and Washington laws set high standards for involuntary mental health holds. They’re designed to protect a person's civil liberties.

To be placed on a mental health hold, a person must be judged to both have a mental illness and, critically, be a serious danger to themselves or others.

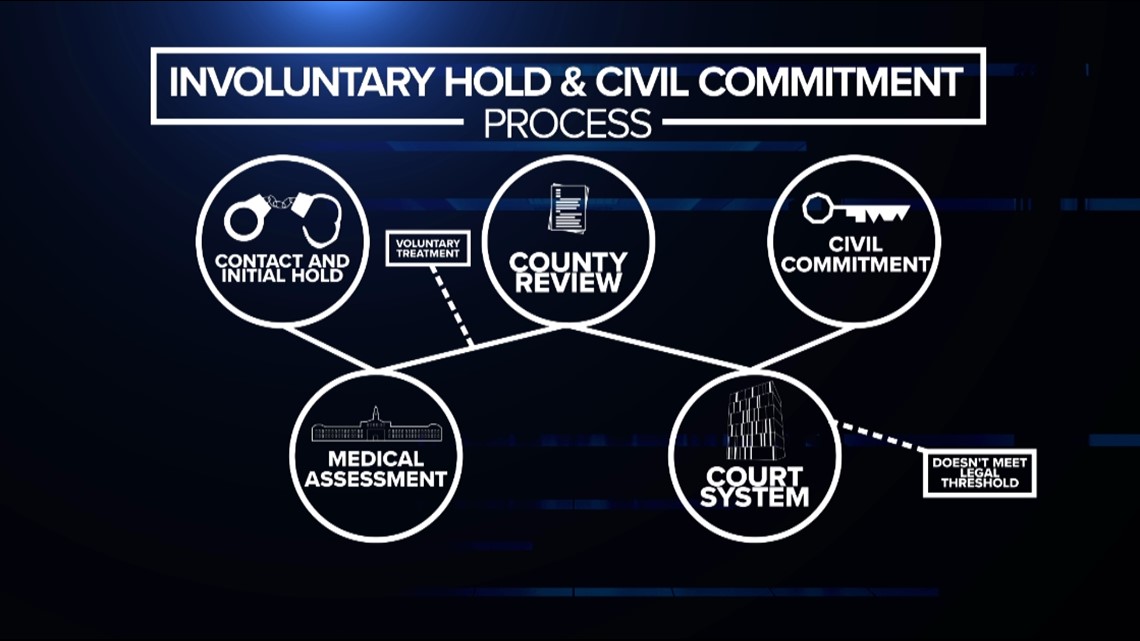

Here's how the process works in Oregon:

If a person shows signs of a serious and dangerous mental illness, the path towards civil commitment starts with temporary detention.

Often, a behavioral health worker or police officer uses a mental health hold to take a person to a hospital for a Notice of Mental Illness evaluation, or NMI.

If a physician finds that person’s mental illness is a threat to their life or the community, the physician will file an NMI, kicking off a complex cycle of reviews and potentially involuntary treatment and detention.

Within three days, a county behavioral health investigator talks to the patient and reviews the NMI. The county worker decides if they agree with the medical assessment that an involuntary hold is necessary.

If the county evaluator agrees, then a judicial hearing is scheduled within five working days of the initial NMI.

At that point, a judge decides if the person fits the legal standard for civil commitment — up to six months of involuntary mental healthcare and treatment.

If at any point throughout this process the individual agrees to voluntary treatment or a diversion plan, then they're likely to be released from the mental health hold and avoid civil commitment.

"Is this person willing and able to be treated on a voluntary basis, that's great, because our administrative rules say treat the person in the least restrictive manner possible," Shumate said.

The second segment of Uncommitted — Personal Impacts — aired Tuesday, August 30.

A KGW analysis of court and government records found that a small percentage of people on a mental health hold end up being civilly committed — either because they no longer meet state standards for a forced hold or because they've agreed to recommended voluntary treatment.

At the same time, fewer people are receiving a Notice of Mental Illness in the first place.

From 2013 until 2021, the number of NMIs filed by doctors in Multnomah County was nearly cut in half. Physicians filed 5,055 NMIs in 2013, compared to 2,600 in 2021.

Despite police officers or health workers arguing that a person’s mental illness poses a danger to themselves or others, most people on a mental health hold are released before any judicial review.

On average, about 12% of people who received an NMI in Multnomah County between 2013 and 2021 received a circuit court hearing.

About 7% ended up with a civil commitment ruling from a judge.

This means most people who received an NMI left the hospital within five days.

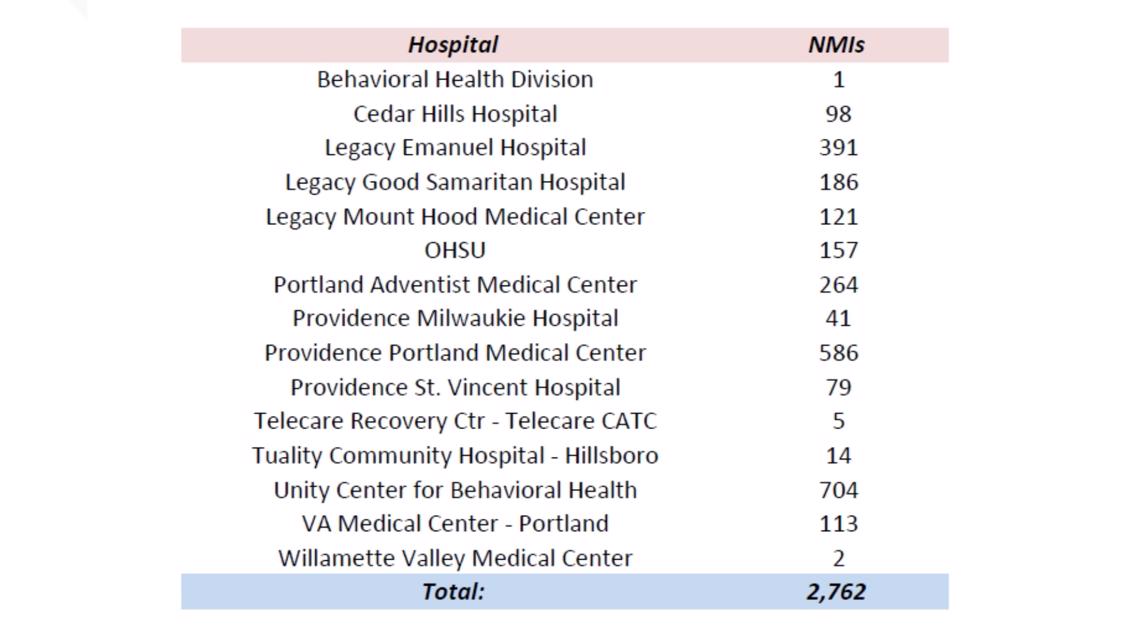

The county’s data also shows which hospitals filed the most NMIs between July 2020 and June 2021.

Unity Center for Behavioral Health, Providence Portland Medical Center and Legacy Emanuel Hospital issued about 60% of the county’s 2,762 NMIs during this period.

High Standards, Big Decisions 'Maintaining a high bar for civil commitments may have...unintended consequences'

Every civil commitment in Oregon must be approved by a judge. The judge will weigh a person's medical evaluation against a legal standard to see if the court finds mental illness is contributing to danger by a standard of clear and convincing evidence.

Civil commitment court records at the county level are sealed to protect individual privacy; however, when cases move up to the appeals court, some of those records become public, offering a look at the complex situations that judges must evaluate.

In October 2021, the Oregon Court of Appeals overturned a civil commitment ruling for a Marion County man diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The man is listed in court documents by his initials, M.L.

The ruling includes testimony from the man's brother, who said M.L. doused himself with household chemicals, including bleach, believing "the government is out to get him and that they're exposing him to radiation."

The brother said M.L. left in the middle of the night to walk from St. Paul, Oregon to Portland because he believed he needed to carry out a mission to resolve the Portland protests. The 30-mile walk would’ve taken at least 10 hours to complete.

Additionally, M.L. had refused medication on eight out of 10 scheduled occasions during his involuntary hold. He did not acknowledge his diagnosis of a mental disorder, according to court records.

The trial court had determined that M.L. should be civilly committed because he was "actively manic" and "dangerous to self." The judge said his erratic delusions and poor decisions put himself in a position of harm.

However, after examining the legal standards and preceding case law, appellate judges overruled the civil commitment, saying the instances didn't establish a "highly probable" threat to M.L.'s safe survival.

Specifically, the judges said M.L. did not "drink" the bleach and his attempted walk to Portland, while "inherently risky," did not end up with him physically harmed.

In September 2021, the Oregon Court of Appeals overturned a civil commitment for a Multnomah County woman — K.M. — who had threatened to kill her neighbors, nonprofit staffers and animal service workers, often over delusions about her cats.

K.M., who was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, is described in testimony as saying she would "dance on [their] grave" and "end us all." Court documents also described a situation where she angrily confronted a director at the Oregon Humane Society.

Court examiners testified that K.M.'s threats had grown increasingly menacing and her "scary" actions had led to three restraining orders against her.

Appellate court judges overturned the civil commitment, writing "this was not a close case," as K.M. did not meet the recently established rule that civil commitment on the basis of danger to others requires the state to prove "actual future violence is highly likely."

By overturning civil commitment verdicts, appellate judges can continuously raise the legal threshold and precedent for involuntary care.

"That becomes case law and continues to raise the bar," Shumate said. "The appellate court says that's not enough, that's not enough."

The third segment of Uncommitted — High Standards — aired Wednesday, August 31.

Judges also support civil commitment verdicts, but recent cases show how much evidence is needed to make this happen.

The Oregon Court of Appeals affirmed a civil commitment ruling in October 2021 in which a person had threatened to kill police officers and tried to enter a gun show to purchase 150 rounds of ammunition, after five people testified his behavior was "escalating towards violence."

In July, judges affirmed a ruling in which a man — D.A. — had stalked a fitness instructor at a Clackamas County gym.

D.A. had previously been civilly committed in 2015 and 2017 after "engaging in stalking behavior" with different people.

On initial review in the hospital, a physician filed an NMI for D.A. because he had "made a vague reference" that he was going to kill himself for violating a restraining order against the gym trainer.

Within three days, a county investigator who had worked with D.A a year before and "had known him for several years" determined that even though D.A. was inconsistent with medication compliance, he didn't meet the "imminent danger" standards for a continued involuntary hold.

However, before D.A. was set to be released without a commitment hearing, D.A. assaulted three other patients at Cedar Hills Hospital, saying they were "trash" and he needed to "take out the trash."

The actual violence and continued "assaultive behavior" towards other patients and staff resulted in appellate court judges upholding D.A.'s third civil commitment, despite later procedural errors.

The Oregon Court of Appeals reversed at least four civil commitment determinations for procedural issues in 2021.

In the explanations of their rulings, appellate court judges frequently reference case precedent, intended and unintended impacts, and the high standard for civil commitment and involuntary treatment.

In some concurring opinions, the judges comment on the process at large.

In a June 2021 case, appellate judges upheld a civil commitment ruling for someone — initials J.W.B. — who had threatened a group of people in his apartment complex with a large kitchen knife over his head, yelling "it's time to leave."

J.W.B had also threatened and been physically aggressive towards hospital staff, including throwing urine and "possibly feces while in seclusion."

Judge Steven Powers, in his concurring opinion, said that while the record in this case didn't meet the standard laid out in prior cases, it "may be worth considering" whether the current high judicial standard is consistent with the ordinary meaning of "dangerous" in civil commitment evaluations.

Powers wrote: "Maintaining a high bar for civil commitments may have the unintended consequence of failing to address mental illness before similar conduct leads to criminal charges and, consequently, the person's entry into the criminal justice system."

How We Got Here 'It's not about whether someone needs treatment, it's whether they can be forced to get it'

Fewer people with severe mental illness are receiving a judge's order for civil commitment each year, and that’s by design.

It's reflective of a decades-long shift in attitudes towards institutionalization for mental health treatment.

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy introduced and signed the Community Mental Health Act into law, the last bill he signed before his assassination.

Key to the bill, Kennedy directed a shift away from treating people with mental illness in large state institutions, saying they must not be "alien to our affections and apart from our community."

"With respect to mental illness, our chief aim is to get people out of state custodial institutions, and back into their communities and homes without hardship or danger," Kennedy said.

A year prior, Ken Kesey's novel "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" had been published. It was a critique of psychiatry and mental health treatment set in an Oregon psychiatric hospital.

Over the decades to come, states adopted new laws in relation to civil commitment and decreased the resources available for institutionalized treatment — instead shifting responsibility to individual counties.

Archived data from the State Library of Oregon shows in June 1954, there were 5,158 beds in use in state mental hospitals.

By 1982, about 30% of those beds remained. Reports from the American Hospital Association show 1,589 available beds in Oregon for mental health use at that time.

Between 2002 and 2022, Oregon has fluctuated between 643 and 777 beds available for state psychiatric use, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

Now, the Oregon State Hospital rarely houses civil commitment patients. In 2019, OSH shifted admission priorities to focus on people awaiting criminal trials, including patients who are considered guilty except for insanity and patients who are unable to assist in their own criminal defense.

For more than a year, the state hospital has averaged less than 20 civil commitment patients per month, forcing local hospitals to provide long-term care and prompting lawsuits from hospital systems who say they’re not equipped to take on this responsibility.

Lewis, with Disability Rights Oregon, said it's encouraging to see fewer civil commitments as people with severe mental illness should be able to choose where they live, not be forced to live in institutions. He also praised the work of county mental health workers.

"People assume, 'oh we're not committing that many people, there must be something wrong with the system,'" Lewis said. "I think the fact so few people end up committed is a sign the threshold is appropriate."

However, others like Brenda Gardner point to what they call a "broken cycle."

"A lot of the problem is that the laws were changed so that their civil rights are what is important, and their safety is not," Gardner said.

After years of learning about the process in trying to help her son, Gardner said most people with serious mental illness are released as they don't qualify for involuntary care.

Then they either refuse or can’t get help on their own until their mental illness symptoms and other contributing factors escalate to a crisis point.

"As far as I'm concerned, the homeless situation is an open-air psych ward," Gardner said. "People that should be in psychiatric facilities or in supported housing with a case worker that checks on them, are instead living on the street and being treated like animals."

The System at Work 'Things weren't right, but no one could figure it out'

Laureen remembers sitting in the back of a police officer's car on the way to the hospital as part of a mental health hold.

At the time, she remembers it feeling like just another adventure. She had gotten used to people being worried about her.

"It was only when I couldn't leave — I was like, 'oh,'" Laureen said. "Then I was unhappy, I was kind of pissed, I wanted to leave."

It was 2009. Laureen recalls how she was making people around her afraid and not acting like the person that they knew.

"My life was a mess," she said. "I had some beliefs that weren't accurate. I would wander into traffic sometimes. Clearly I was not making good decisions to keep myself safe."

She remembers overspending, making nonsensical phone calls, trespassing, and believing she was a rock star set to go on tour with Pink.

After police officers dropped her off at a hospital, a physician filed an NMI for her, starting an involuntary hold.

She was then diagnosed with Bipolar 1 Disorder, prescribed new medication, connected with a therapist and supported by her concerned family.

Laureen agreed to start a voluntary treatment program, which included three weeks of partial hospitalization and evaluations.

She said she's lucky, the process changed her life.

"I don't know if I would be alive and it's hard to know what would've happened if somebody hadn't stepped in," she said.

Laureen says her story is an example of the system working well: an involuntary hold used as a last resort, a correct diagnosis and medication that helped, an encouragement and exit into a voluntary program that she fulfilled.

In her case, a forced hold — the handcuff on civil liberties that it is — was the right move forward.

At the same time, she said many people don't have the same success.

"I do acknowledge that there are people who do slip through the cracks every single day and that breaks my heart," she said.

Laureen knows this because she's now a peer support specialist, working in tandem with clinical partners, therapists, psychiatrists, and social workers who respond to people experiencing severe symptoms of mental illness.

"So, you're having a really bad day, I've been there," Laureen said, explaining how she works to connect with people experiencing a mental health crisis. "It did get better."

She said she wants people to understand there are ways to manage mental illness and for the public to not view people with mental illness as "scary."

Laureen described how mental health workers search tirelessly for solutions — offering treatment, housing and support services to people who need it.

At the same time, she said she's usually not surprised to hear someone she knows was placed on an NMI at a hospital.

She also understands the frustration of medical professionals when a person is released within days, often because there's not enough evidence that they’re an imminent threat to the community or their own safety.

"There are more times than not when I'm like, 'are you kidding me, they didn't do more?'" she said. "This person is clearly suffering."

Gaps in the Cycle 'It underscores that the system is imperfect - what else can we do?'

On May 24, dozens of Portland Police officers rushed to the MAX stop at Cascade Station, not far from Portland International Airport.

Investigators said a man, Marcus Tate, had taken two people hostage on the MAX train, armed with a knife and a barbecue skewer.

After a standoff, a special police unit used two flashbang grenades to stun Tate before arresting him and rescuing the hostages.

Tate pleaded not guilty to multiple felony charges.

Following the arrest, a spokesperson with the Portland Police Bureau revealed police officers had stopped Tate just the night before. They said Tate had a "physical altercation" with officers during an "apparent mental health crisis."

Officers chose not to take Tate to jail. Instead, they used a peace officer's hold to take him to the hospital for a mental health evaluation.

Tate was evaluated and stayed in the hospital overnight, only to be released the next morning, just hours before the incident on the MAX train.

"To get a person to a hospital and then to learn that they were released right away, it underscores that the system is imperfect," said Lieutenant Chris Burley of the bureau's Behavioral Health Unit.

Police officers are often the initial point of contact for a person experiencing a mental health crisis. In cases where a person might have committed a crime, officers are trained to weigh whether a mental health hold and treatment would be more productive than incarceration.

"We're wanting to do what's best for the community, what's best for the person that's suffering from mental health symptoms, trying to figure out how to navigate that without always having all the information," Burley said.

He said what's most frustrating for police officers is that they can choose a peace officer's hold and take someone to the hospital for medical help. Then, they'll see the same person, days later, seemingly experiencing another mental health crisis.

"The officer is trying to determine, 'OK, the hospital last time said this person didn't fit criteria. So, was I wrong in assuming this was because of mental illness? Should I just take this person to jail?'" Burley said.

To add to the confusion, police officers file paperwork to accompany a mental health hold but they don't receive notice when an individual is released from a medical facility.

This is purposeful, as mental health evaluations and medical records are protected private information. However, Burley said it can leave officers feeling hopeless.

"To not know where they can turn to get that person the help they need is concerning, is upsetting, and it feels like we're not treating all of our community members with the dignity and respect they deserve," Burley said.

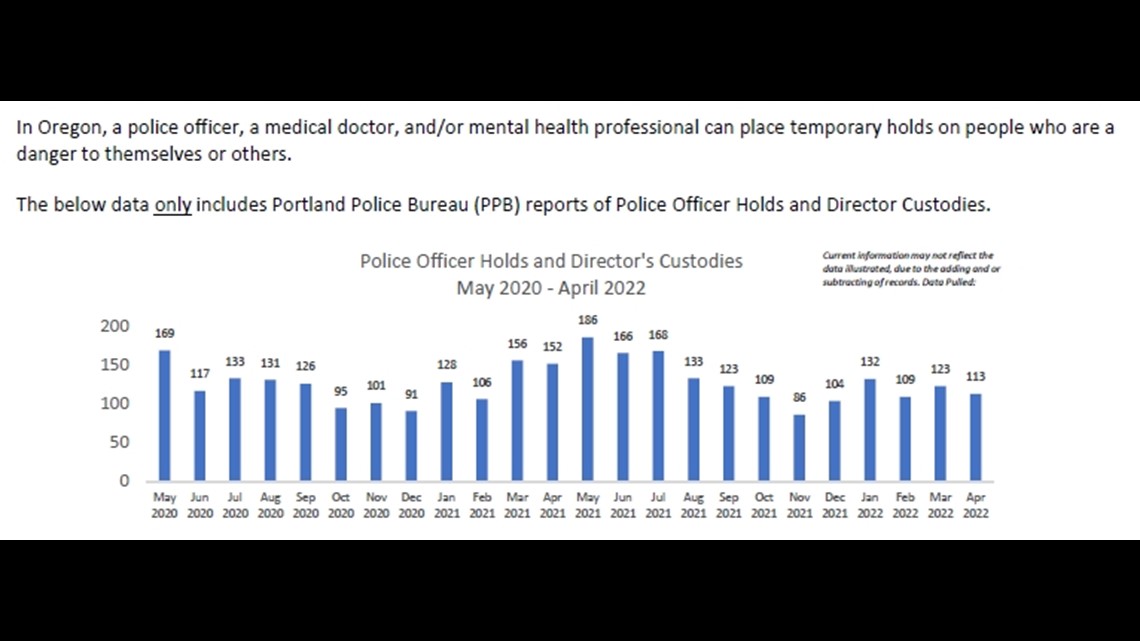

Between May 2020 and April 2022, the Portland Police Bureau issued an average of 127 mental health holds each month — or about four per day.

In total, PPB report 3,057 holds over this two-year span.

These police officer or director's custody holds are temporary and come before a doctor would issue an NMI.

Hold standards are similar to the civil commitment standards that county evaluators use — officers must determine a person is "imminently dangerous to self or to any other person" to initiate a hold, according to Oregon law.

About 13% of the holds between May 2020 and April 2022 involved a person who had been placed on multiple holds by Portland Police.

This number is likely an undercount, as PPB was not able to identify more than 600 people who didn't have identification, didn't give their name, or gave a false name during a hold.

The repeat case count of 13% also doesn't include anyone who's been placed on a mental health hold by another agency's team, like Cascadia Health or a different police department.

Still, in Portland alone, at least 389 people over the past two years were judged by police officers to be an imminent danger to themselves or the community, taken to the hospital for help, released, and then later judged to be dangerous again.

"[Officers] are coming in contact with the same person and unsure of what they're supposed to do," Burley said. "They believe the person has a mental illness and they're not receiving treatment and they want that person to be safe, but [there may] also be victims to crimes they're responding to."

Burley adds most of the people who officers contact or arrest do not have a mental illness, and people with mental illness are not more likely to commit crimes.

He said it's a constant collaboration with the District Attorney's office, jails, hospitals and behavioral health workers to try to determine what's best, but it can feel like a futile cycle despite best efforts from all levels.

"There's no doubt that people recognize the system is not working," he said.

There's another notable contributing factor that's complicating mental health evaluations and involuntary holds: Drugs, alcohol, and intoxication.

Burley said a common form of methamphetamine that officers are seeing people use produces side effects of extreme paranoia — which can make it difficult to determine whether a person is experiencing a mental health crisis, intoxication, or both.

RELATED: 'Such a state of paranoia': Portland's meth crisis apparent on city's streets, former addicts say

Even if officers decide on a hold for mental health evaluation, substance use does not fit the criteria for an NMI. If a doctor or evaluator determines dangerous behavior is due to drugs or alcohol instead of mental illness, they can't hold a person for treatment against their will.

"What we see is people that come into a facility to get treatment, if they have any type of substance on board, they oftentimes get released," Burley said. "[When that happens] we have not necessarily made the community a safer place...we need to change the system to better address the issues we're seeing right now."

In the future, Burley said if PPB provides body worn cameras to officers, that might help show medical providers, evaluators and the courts what officers saw to initiate an involuntary hold — providing more information to review.

Out of Options 'We were completely off-guard, we had no history of mental illness in our family'

Growing up, Eric Gardner was a social and athletic kid with a great sense of humor, his mother Brenda Gardner said.

By the time Eric's symptoms emerged and his behavior changed in his early 20s, his parents didn't know what to do.

"We were caught completely off-guard, we had no history of mental illness in our family," she said. "We had never been involved with social workers or the police."

During outbursts, she said Eric would threaten that if his parents tried to take him to a psychiatrist, they'd never see him again.

When Eric started acting violently, his father called the police for help.

"They just took him straight to jail, and when he got out of a jail, a no-contact order [with us] was issued, and we didn't know that was going to happen either," she said.

Despite the no-contact order, the Gardners welcomed Eric back into their house six weeks later. He had been living with family friends.

His behavior fluctuated. The Gardners describe Eric as intelligent and high functioning, but threats of violence and disturbing text messages persisted.

Alan Gardner, Eric's father, ran a bar across their bedroom doorframe at night out of fear for their own safety.

"He had threatened to kill us," Brenda Gardner said. "We were afraid he could break down the door and come in and kill us at night."

When placed on a mental health hold at a hospital after a suicide scare, Eric Gardner didn't meet standards for civil commitment.

When released with a plan to attend day treatment programs, he stopped going and stopped taking medication — complaining of side effects.

"I think that should be his right to refuse medication, but I think he should be in supported housing if that was the only choice," Gardner said. "I'd rather have him hospitalized than spending winters on the street."

Eric moved to Seattle, where he went to college. He's currently homeless in the Capitol Hill area.

Gardner said it's his choice — he refuses other options and living at the homes of family members was untenable.

He was arrested in December 2017 for criminal trespass after breaking into someone's home, which Brenda Gardner said he likely did to try and stay warm.

That caused Eric to lose disability benefits — his parents had hired an attorney to help him obtain them and it removed Eric from a subsidized housing waitlist.

"The housing piece of it, there's nowhere to send them, no advice to give about how to house them," she said. "As a society, I just think it's so unacceptable that we've chosen not to care for people who are truly ill."

Gardner said she's grateful they're able to visit Eric from time to time, as he's made friends with a couple who lives in a nearby apartment. They can now bring him food and clothes and have brief interactions.

She said, as parents, it's still heartbreaking. It's why she's open to sharing her family's story — she wants more people to know about this process.

"Most civilized countries do a better job with the mentally ill than we do in this country," she said.

The fourth segment of Uncommitted — What's Needed, What's Next — aired Thursday, September 1

What's Needed, What's Next 'The needs have changed, why shouldn't we change?'

Many people involved with the civil commitment process — from family members to doctors to behavioral health workers to police and judges — say the state standards for forced mental healthcare need to be reviewed.

"You know, civil commitment laws haven’t changed significantly since they were written in the 70s," Shumate said. "The needs have changed, treatment options have changed, treatment programs have changed."

Behavioral health experts point to the overlap between mental healthcare and other areas of societal need — such as homelessness, affordable housing, addiction and violence prevention.

Shumate said civil commitment should be a last resort, but it might be time for everyone in the process to ask — is the bar where it should be?

She and others recommend that Oregon lawmakers form a group with all stakeholders and people involved to review civil commitment laws to see if they're meeting community needs and intended purposes.

"This is such an important law and such an important process that impacts people's lives so significantly, that I think to let it sit idle in the statutes doesn't serve us well," Shumate said. "It doesn't serve our community well and I don't think it serves people who are living with mental illness well."

Understanding that KGW's analysis found close to 90% of people taken to a Multnomah County hospital on a forced mental health hold were released within five days, Shumate said it's possible that many people are not receiving care that they need.

"They may be discharged from a treatment setting without the length or level of treatment that’s recommended and they leave that place continuing to experience significant symptoms of their illness," she said.

From the perspective of police officers who see mental health holds that fail to help people displaying severe symptoms of mental illness, Burley said something should be done to stop perpetuating a futile cycle.

"I do think as a community we need to come together and say, as a state, are we comfortable with where we're at right now?" Burley said. "Folks do not feel that what is going on in our community is acceptable."

Burley said people with severe mental illness can be released because their symptoms stabilize in a hospital, only to deteriorate again without mental healthcare.

"I think it is telling, they've got a bed, they've got meals, they've got a roof over their head, some treatment," Burley said. "For some folks that's what they need, so why would we stop providing that to them?"

However, he recognized why civil commitment standards require proof of imminent danger and how this threshold was set.

"The bar is extremely high, and that has historical reasons for it — past historical abuses," Burley said.

Lewis, as an advocate for people with mental illness, said the bar is in the right place to protect individual civil rights.

"I think rather than looking at the standard for civil commitment, the thing that would make the biggest difference for people with mental illness and for the community is to say — how do we keep people from ever getting to that point?" Lewis said.

He added mental health workers rightfully encourage any type of voluntary treatment over civil commitment.

Instead of changing state standards, Lewis said the system must do a better job of caring for people when they’re released from a mental health hold.

"We need more resources in the community, more placements for people who need wraparound services, more supportive housing, medication management," Lewis said. "A lot of the things leading to being at the level where they might qualify for a commitment...they are things we could've helped earlier and kept that danger from ever manifesting in the first place."

When asked what can be done if an individual refuses mental healthcare resources, housing, or treatment plans upon release, Lewis said he believes in follow-up care from behavioral healthcare workers.

"Nine times out of 10, if you are able to spend more time with a person with mental illness and really understand what they need, there are ways to connect them with those resources, even if they are initially reluctant. You can build that trust and that relationship that it really takes to do that," he said.

Mental health housing is the priority for Brenda Gardner, who said she and other families often lament the lack of available options.

"There's very little housing for the mentally ill," Gardner said, referencing wait lists and other restrictions on qualifying for housing. "If [Eric] had a little bit of supported housing I think he could manage. There's a desperate need for housing."

Gardner views the shift away from state institutionalization for mental health treatment as an opt-out.

"The laws were changed, in my opinion, for the convenience of government to not have to care for [people with severe mental illness], not make them go into treatment unless they want to," Gardner said. "Way too far in that direction [in favor of civil rights over care.]"

Laureen said she focuses more on personal relationships than systemic change in her current role of peer support, but that doesn’t mean she lacks a passion for change.

"It breaks my heart when people slip through the cracks and don’t get the treatment they deserve, and one thing I’m super passionate about is that people who are suffering don’t belong in jail," Laureen said.

Burley agreed, but said when an officer has tried calling mental health resources and taking someone to a hospital for evaluation and treatment, when that officers sees the same person in crisis again — and there’s evidence of a crime — it can be a tough call.

"Prior to release, folks are trying to do the best they can to identify if there is something out there for [people with mental illness] to go to, but in some cases there isn't and it needs to be a meaningful place with support," he said. "[We want that] so again we don't come back and continue that cycle of interaction with the criminal justice center."

In addition to the PPB Behavioral Health Unit's work, Burley praised the efforts of Cascadia Health workers, including Cascadia's Project Respond Team and their crisis workers.

In 2021, Project Respond made 28,943 contacts and initiated 524 Director's Custody Holds for involuntary assessment.

These contacts included face-to-face meetings, phone support, peer support, care coordination, case management, and other aspects of behavioral health care.

Cascadia Health reports 190 of the 524 holds were singular — one hold issued for one person in 2021.

The rest of the mental health holds involved a person who was placed on more than one hold by Project Respond workers.

Shumate agreed with Lewis that preventative care and expanded mental resources are needed to better care for people with severe mental illness.

Multnomah County is building a behavioral health resource center in downtown Portland, set to open later this year.

Clark County has proposed a community-based behavioral health facility to serve up to 48 patients.

Portland recently expanded the Portland Street Response program to help people with mental health and behavioral health crises.

Shumate said the recent cultural focus on mental health means the process isn't in need of a complete overhaul.

"We have some excellent components in our systems, there are great people out there, we don’t need to throw out the baby with the bath water," she said. "We need to make sure we are optimizing the resources that we have, and where we’re building, we’re filling in the gaps."

She said that could mean step-down options for people exiting the civil commitment process, providing a different type of care.

Doctors and police point to the cross-section between mental illness and addiction, saying there's a need for people and places dedicated to help people across the spectrum, rather than provide options for mental healthcare or addiction recovery in isolation.

Whatever the focus, Shumate said it's past time to re-evaluate and see the community commit to something better.

"We absolutely need to pay more attention," she said. "There's a lot of need to close those gaps."