PORTLAND, Ore. — The worst of the foreclosure crisis passed years ago, but for some of those who lost their homes it never really ended.

Almost a decade later, former homeowners are still trying to fend off the Portland Water Bureau, which sent them to collections over unpaid water and sewer bills that accrued after they were evicted.

“Why go after people when they were kicked out of their house?” asked John Laird, who lost his Portland home to foreclosure.

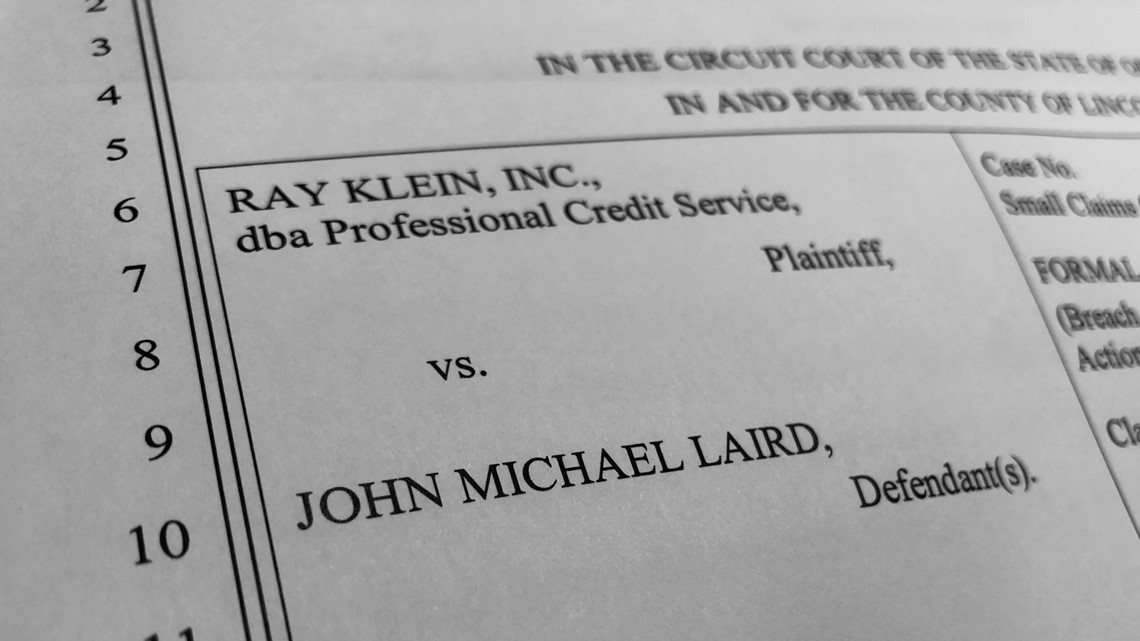

Laird knows first-hand how aggressive debt collectors working on behalf of the city can be. He has been sued twice by a private collection agency working on behalf of the Portland Water Bureau. The bureau was trying to collect on water bills accrued after Laird had vacated his foreclosed home.

In the first suit, Laird questioned the fairness of the water bureau charging him for services he didn’t use. The case was dismissed.

Two years later, the collection agency, Ray Klein Inc., sued Laird again over the same $2,000 bill. The Portland Water Bureau wouldn’t let it go.

“They’re wasting time. They’re wasting energy,” said Laird. “It’s taken a huge toll on me to have to relive the crappiest period of my life.”

In a series of reports titled “The Cost of Collections,” KGW has examined the aggressive tactics used by the City of Portland to force people to pay up, including the use of private, third-party collection agencies. Our reporting questioned whether the city’s efforts to recover on past-due accounts are overly punitive, undermining the city’s own effort to keep residents housed, employed and able to meet their essential needs.

Sued multiple times over the same bill

John Laird took a beating in the financial crisis. Sales dried up at work, his income took a hit and Laird struggled to pay the mortgage on his house in a gated community on Hayden Island.

Like millions of other Americans, Laird lost his home to foreclosure during the economic downturn.

“It was terrible,” said Laird.

The bank evicted the Portland homeowner on February 6, 2010. Before he vacated the property, Laird said he called various utilities asking them to shut off service, including water, power, cable and phone. He turned off the water main to avoid frozen pipes, sent the keys to the bank and moved out.

“Sign was on the wall. Dream is over,” explained Laird.

Over the next few years, Laird struggled in life. He moved to California. He was broke, suffered a mental health crisis and became homeless as his marriage fell apart.

“During the divorce separation period, I found myself living out of my Yukon in a twin bed with my dog,” said Laird.

And through this financial and personal crisis, the Portland Water Bureau never stopped billing him.

Laird didn’t live in his Hayden Island home anymore. He didn’t use the water or sewer, but he was still being charged for it because the bank delayed foreclosure and hadn’t removed his name from the title.

“Farthest thing from my mind was that stupid water bill,” said Laird.

The Portland Water Bureau sent Laird to a private collection agency called Ray Klein, Inc., also known as Professional Credit Service. The collection agency can charge fees and interest on delinquent accounts as part of its contract with the city of Portland.

In September 2017, Ray Klein – working on behalf of the water bureau – filed a claim in Multnomah County court against Laird. The private collection agency was seeking roughly $2,000 for the old water and sewer bill including interest, fees and costs.

Laird challenged the small claim and the case was dismissed after Ray Klein failed to respond.

“I was thinking, this is all behind me,” said Laird. “I don’t have to think about that crummy time in my past.”

The Portland Water Bureau didn’t give up.

Two years later, the collection agency sued Laird again on behalf of the water bureau over the same $2,000 water bill.

Ray Klein filed the October 2019 case in Lincoln County, where Laird currently resides. Again, Laird challenged the collection agency and the case was dismissed.

“A lot of people would assume that if you got wrongly sued for a debt that you don’t owe and it got dismissed that would be the end it. But, the lawyers for debt collectors are clever,” said consumer rights advocate and attorney Michael Fuller, who represents Laird.

In November 2019, Fuller filed a federal lawsuit on Laird’s behalf against Ray Klein for unlawful debt collection. The parties reached a settlement agreement and the civil case was dismissed. As part of the deal, Laird explained he no longer owed the Portland Water Bureau.

Ray Klein Inc. declined to comment on Laird’s case, citing a company policy against discussing individual accounts. In an email to KGW, chief marketing officer Huntley McNabb said it is never the company’s intention to file a claim against someone who doesn’t have the ability to pay. The procedures for filing claims are very labor intensive and occasionally mistakes are made, explained McNabb.

The Portland Water Bureau declined to comment on the specifics of Laird’s case because of customer privacy concerns.

It’s not clear why the city of Portland continued to try and collect on years-old utility bills from the former homeowner instead of going after the bank that took possession of the property.

“The large banks get bailed out and consumers are left to deal with the consequences,” said Fuller.

Emails and published case summaries show the city ombudsman had previously raised concerns about the water bureau’s approach to delinquent accounts involving distressed property where banks took possession but delayed foreclosure.

In 2015, the city ombudsman recommended the water bureau stop collection efforts against a former Portland homeowner who declared bankruptcy. Instead, the city watchdog suggested the water bureau go after the bank for unpaid charges.

In 2018, the city ombudsman investigated a case where the water bureau, though a collection agency, tried to hold a former homeowner responsible for a $4,000 water bill that accrued after he vacated the home.

In both cases, the ombudsman cited an ordinance that the Portland City Council passed in response to the foreclosure crisis. The 2012 law gave the water bureau the authority to pursue banks that took possession of homes but delayed foreclosure.

The Portland Water Bureau claimed there were recent examples where it has pursued the bank or written-off unpaid charges.

“If we have evidence there was an error, that you were no longer the responsible property owner, we can pull back those fees,” explained Felicia Heaton, spokeswoman for the Portland Water Bureau.

The water bureau handles billing for itself and the Bureau of Environmental Services.

Unlike other utilities, the water bureau and bureau of environmental services don’t stop billing when a customer moves out or calls asking to stop service. They are required under the city’s municipal bond agreements to continue to collect water, stormwater, sewer and superfund fees.

The water bureau uses the name on property records to establish who gets the bill. The challenge is figuring out who is responsible for these charges on a distressed property.

“We don’t have a way to find out that a home has been foreclosed on, unless a customer calls us,” said Heaton. “There’s no mechanism in place that requires a bank to tell us at a certain time, so it is extremely important when things start heading in that direction, give us a call.”

Heaton encouraged customers to provide a copy of an eviction notice or take a photo of the lock box on the door to help prove the bank has taken possession of a home so the bank or lender can be held responsible for the water bill, not the former homeowner.

“If at any point, you have the ability to show the ownership of the property was transferred, we’re ready to act,” said Heaton.

Which is fine going forward, but how about people who were evicted during the housing crisis? They were never told to take photos or gather evidence.

“It could have all been taken care of instead of dragging me along for the ride,” said Laird. “It’s just bad business practice.”

If you have a suggestion for an investigation, or want to blow the whistle on fraud or government waste, email CallKyle@kgw.com.