ALOHA, Ore. — One year after opening, a hotel turned housing facility in Washington County is providing an escape from homelessness to more than 50 people.

While there are clear success stories, KGW also found that the new taxpayer-funded building isn’t quite being used as it was sold to the public — evidence of the gap between intent and reality in addressing the homelessness crisis.

Government agencies promoted the building as a place for people with both housing and higher needs — such as severe mental illness or substance use disorders — but after a year of operation, officials say its best used for independent living with optional support available.

“I think we’ve learned a lot (about) who we can best serve and who really needs a higher level of care that this independent living setting was just not designed to offer,” said Marcia Hille, executive director of Sequoia Mental Health Services, whose case managers provide support to residents at the building.

Heartwood Commons, the new name for the renovated Aloha Quality Inn, is Washington County’s first building of its kind, offering 54 studio units with on-site assistance for people who need a more stable place to live.

Washington County bought and redeveloped the building for about $10 million, most of which came from the Metro Housing Bond which voters approved in 2018.

The county is also paying about $1.5 million each year for support services and housing subsidies.

That funding comes from the Supportive Housing Services tax that voters approved in 2020 — a 1% tax on high-earning individuals and businesses.

Terrence Jackson moved into Heartwood Commons in April.

“This is a blessing for anybody,” Jackson said. “Having your own place, a place to cook, you’re not in the cold, you’re not in the rain.”

Jackson said he worked as a contractor installing doors and windows in Lake Oswego, but he lost that job and quickly ran out of options — which led him to homelessness.

“I lost my truck so I couldn’t sleep in that anymore, and so the shelter was next,” he said, describing how grateful he now feels to be living in a subsidized apartment. “From there, it was like little jobs here and little jobs there, and it just wasn’t enough. It wasn’t steady pay.”

While Heartwood Commons is a lifeline for people like Jackson, others feel its purpose was miscommunicated and leaves a significant housing need yet to be filled.

Sally Reid said she was ecstatic when she heard about the Heartwood Commons project, promoting it to many people she talked to.

“On paper, it looked beautiful, it looked exactly like what people needed,” Reid said. “I prayed for four years that my son would get in there.”

Reid’s son Phillip has a serious mental illness and has experienced cycles of homelessness for years.

In September, a few months after Heartwood Commons opened, Phillip signed a lease for a room at the new complex.

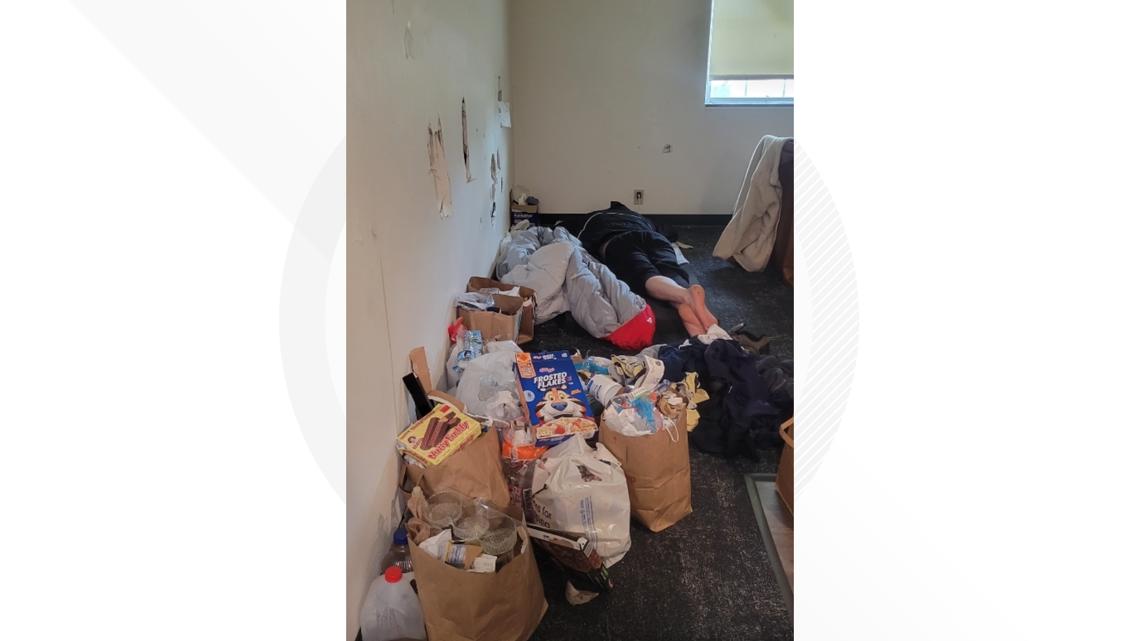

Six months later, Phillip was evicted from the building.

Reid told KGW her son has been homeless again for the last two months — an example of someone who needs more support than Heartwood Commons seems able to provide.

“It was a battle of behavioral health versus housing, and behavioral health lost,” Reid said. “Which means the people who really needed this are no longer here.”

The goal of ‘permanent supportive housing’

Heartwood Commons is described by government agencies as a "permanent supportive housing" building.

“I typically say there are as many definitions of that term as there are people in the room,” Hille said, acknowledging how invested parties likely had different expectations for the property.

In a virtual presentation introducing the Heartwood Commons project, a Washington County employee explained how the property would offer more than just housing.

“(We’ll have) behavioral health support and case managers on site to help support high-needs, vulnerable populations to maintain long-term successful tenancies,” said Jessi Adams, capacity programs supervisor for Washington County's homeless services division.

Reid said she was thrilled the county built something that could provide all the support her son needs.

Chelsea Blair, program coordinator for the county, explained in the virtual meeting that Heartwood Commons would serve a high-acuity population.

“These are generally people who have higher levels of being hospitalized who have maybe been within the jail and prison systems, so this can be really helpful for that particular group,” Blair said.

The description page on Metro’s website for Heartwood Commons says the building serves the “highest-acuity and chronicity individuals in a community.”

It lists Heartwood Commons as a place for people with “serious and persistent mental illness,” people coming out of institutional settings, people struggling with “substance use,” and people who are “unlikely to be successful in a traditional housing setting.”

Jes Larson, assistant director of Washington County’s Department of Housing Services, told KGW that permanent supportive housing has one goal.

“The idea is that we want to make sure that through PSH no one ever returns to homelessness,” Larson said.

However, Larson said Heartwood Commons was always designed for "independent living" with support services on-site, but optional for residents.

“So, if they're not choosing to engage in the behavioral health services on site or the case management supports on site, that's totally their choice, but they might not be getting the care they need inside their apartment and there's no effective way to intervene,” Larson said.

The gap yet to be filled

Reid told KGW she was surprised by the lease her son Phillip signed, as it felt like a standard apartment lease, not tailored to people with higher needs or severe mental illness.

The lease document, reviewed by KGW, required 24-hour notice for anyone to enter a room and check on a resident.

It also listed threatening actions as cause for eviction, which Reid said she knew would be a problem based on her son’s mental health needs.

“For people who are chronically homeless and ill it was too much,” she said. “You can’t expect that.”

UNCOMMITTED: Nearly all of Oregon State Hospital's beds go to criminal patients, all but ending civil commitment in Oregon

Washington County reports 12 "exits" from Heartwood Commons in its first year in service. Some residents transferred out, three went to jail or prison, and three died.

Reid said there wasn’t a fallback option for her son or others who needed more support than Heartwood Commons could offer.

“There was no stopgap measure put in place to take care of people if they were evicted,” Reid said. “So, they basically just went back to a shelter and back on a waiting list, which is extremely sad and upsetting.”

She praised the Sequoia case manager assigned to work with Phillip who continues to check up on him as he looks for another place to live.

Hille told KGW that the county, service providers, and the community all likely had different expectations for what Heartwood Commons would be.

“To serve a higher level of acuity, you would really need to staff it with more clinical positions,” Hille said. “A primary thing we’ve learned is more about the profile of the individual that’s likely to be successful (at Heartwood Commons).”

She praised how many people have been helped into housing by the new building but said the first year of operations shows how Oregon desperately needs combined housing and treatment facilities — places that can take care of people with mental illness and substance use disorders.

“The focus needs to be on developing more of the settings that are appropriate for their needs,” Hille said. “We’ve come a long way, but we’ve got a long way to go.”

Reid thought Heartwood Commons was destined to fill that gap, but now she’s waiting for another option for her son.

“I think for now going forward, it’s perfect for what the county is now using it for, but it’s sad we don’t have an alternative,” Reid said.

As of May 2024, the 54 rooms at Heartwood Commons were nearly all full of people transitioning from homelessness to independent housing.

Terrence Jackson, who told KGW he’s finally comfortable and thankful for the rental subsidies, said he’s motivated to eventually move out to his own place once again.

“It’s given me an opportunity; I’m actually a lot happier than being in the shelter, that’s one step closer to where my goals are,” Jackson said.