Two days after Kris Cronkright moved to The Dalles in the picturesque Columbia River Gorge, she noticed a pungent smell.

“It literally woke me up,” she said. As a kid, Cronkright walked along railroad tracks so she knew exactly what the smell was. “It instantly was nothing other than railroad tracks – railroad ties.”

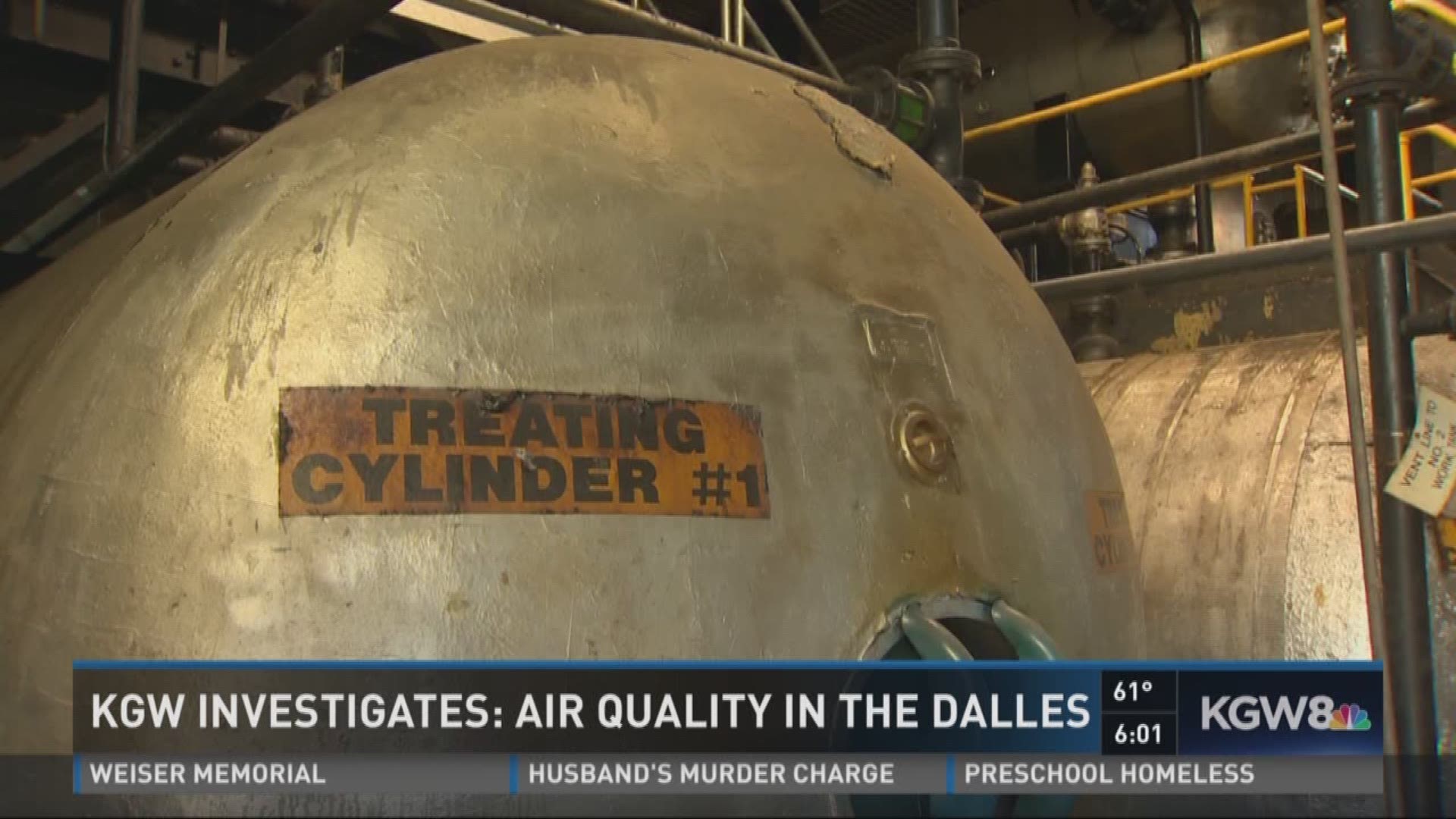

Cronkright, who moved to The Dalles with her husband and young son in July 2014, learned the railroad smell was coming from AmeriTies, a facility that uses a coal-tar byproduct called creosote to treat wooden railroad ties for Union Pacific. Creosote contains several known or suspected cancer-causing chemicals, including naphthalene, the substance producing that pungent odor.

Cronkright also learned that AmeriTies wasn’t violating its Oregon air quality permit. In fact, Amerities could release twice as much naphthalene into the air and still fit within the guidelines set by the state.

Oregon’s lenient air pollution permits don’t consider the impact of toxic emissions on human health, which means numerous industrial polluters like AmeriTies are legally contaminating the air in areas where people live.

The last chance Cronkright had to get the state to crack down on AmeriTies was to complain about the smell. She embarked on a years-long fight to change AmeriTies’ operations, using a little-known state policy that prohibits businesses from releasing “nuisance odors” that impact residents’ quality of life.

The policy is backed by a five-year-old program called the Nuisance Odor Strategy, which gives the state’s Department of Environmental Quality authority to investigate otherwise law-abiding industrial sites that release odorous fumes.

But while state officials say the program is an effective last resort for pollution concerns, some residents say it is proof that Oregon doesn’t take toxic threats seriously, instead turning them into subjective complaints about foul smells.

DEQ fields thousands of pollution complaints each year

Oregonians like Cronkright, who are concerned about potentially toxic issues in their neighborhoods, can complain to the DEQ through an online pollution complaint form on the state agency’s website.

The DEQ receives thousands of these complaints each year.

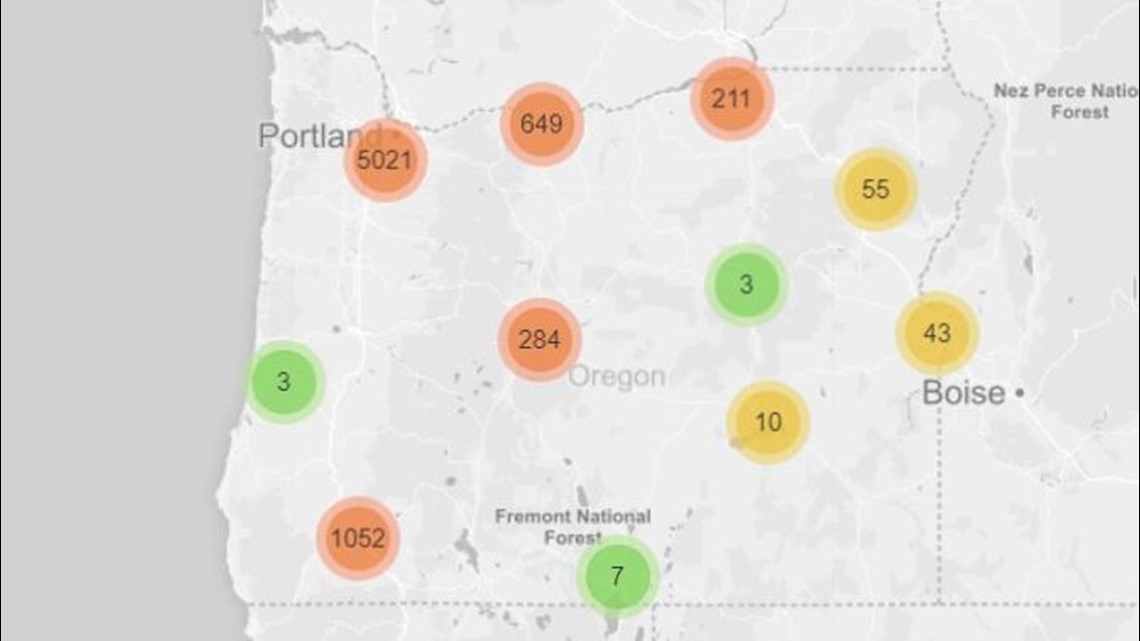

KGW obtained the DEQ’s pollution complaint databases for 2016 and 2017. An analysis showed that 8,270 pollution complaints were filed across the state over the course of two years, 44 percent of which came from the Portland metro region. Forty-one percent of the pollution complaints were odor complaints.

Complaints range from homeowners reporting neighbors burning trash, to residents who witnessed businesses contaminating waterways, to concerns about acrid smoke emanating from nearby industrial sites.

“Caustic white smoke which burns eyes and throat billows through the neighborhood. Some of the children who live close by experience asthma attacks as a result,” one complainant wrote about a residential property’s open burn pile in Salem.

“I observed along the hillside, several acres covered in heavy, thick, black oil. My son… indicated that an oil truck had dumped its load of oil across several of the acres,” a resident wrote about a piece of recently clear-cut land in Douglas County.

Hundreds of business and individual pollution sources were named in the complaints. Many other complainants didn’t know the source of the pollution they smelled or saw.

“There is such a strong chemical odor in the air I thought the pipeline nearby erupted, or a spill may have happened on N. Columbia nearby. It is horrible, toxic smelling, and burns the eyes and throat,” a North Portland resident wrote.

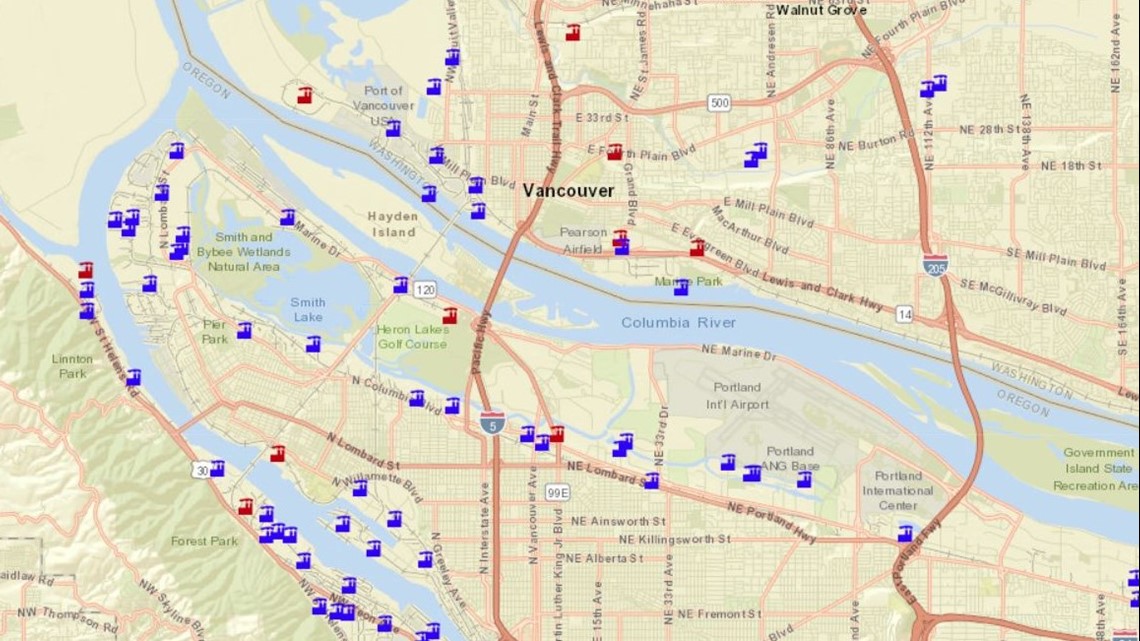

Click here to view the interactive map for all DEQ complaints. Zoom in to read individual complaints. Note: About 1,000 complaints do not appear on the map because they did not contain location data.

Some businesses generated far more complaints than others. While most businesses mentioned in the complaints had one or two grievances filed against them, several industrial sites popped up again and again in the DEQ database. Ten companies stood out from the pack, racking up at least 1,380 complaints among them.

AmeriTies amassed the most complaints, with more than 500 filed against the business in 2016 and 2017. Second was Daimler Trucks’ manufacturing plant in North Portland, and third was Grimm’s Fuel Company, which processes compost in Tualatin.

Six out of the 10 top pollution complaint sources were in the Portland metro area. Two were in the Willamette Valley, one was in the Columbia River Gorge and one was in Stanfield, a rural town near Pendleton in eastern Oregon.

Click here to view the interactive map for the Top 10 pollution complaint sources

Groups of neighbors have banded together to complain about many of the top odor generators and try to spur government action.

Cronkright is part of The Dalles Air Coalition, which has dozens of members who file complaints and compare notes about odors they believe are from AmeriTies.

A neighborhood group in Tualatin, Clean Air Safe Environment, files complaints against Grimm’s Fuel. Several Portland-based air coalitions file complaints against the city’s top odor generators such as asphalt producer Porter Yett, and oil re-refineries APES and ORRCO.

The DEQ follows up to learn more about many of the grievances, but until five years ago the agency didn’t take any enforcement action against otherwise law-abiding companies that generate odor complaints.

History of odor complaints falling on deaf ears

In 2001, Oregon outlawed odors that cause a nuisance – meaning a frequent, intense smell that impacts people living nearby.

For 12 years after that, the DEQ did nothing about odor complaints for any business with a valid air permit, since there was no protocol for cracking down on otherwise law-abiding polluters.

“We would get a lot of complaints about certain companies and yet we would not be able to say the company was violating any part of the law, but yet the complaints would continue,” said Bryan Smith, who now leads the DEQ’s Nuisance Odor Strategy program. “It felt to the public and to us that we were spending a lot of time trying to manage these complaints but not necessarily having a resolution.”

Smith was the DEQ’s small business assistance coordinator in 2013, when the agency approached him with a proposition. Smith agreed to tack on a new project to his workload, cracking down on the permitted polluters that generate the most odor complaints.

State starts investigating ‘nuisance odors’, but prefers settlements

Smith helped craft the new odor strategy and lay out a legal protocol for how the DEQ could crack down on complaint-generating companies.

What resulted is a complicated policy that triggers an investigation of a nuisance odor if a permitted company generates at least 10 complaints from 10 different addresses in a 60-day period.

The DEQ also considers several criteria when deciding to launch an investigation:

- Frequency of the emission

- Duration of the emission

- Intensity or strength of the emissions, odors or other offending properties

- Number of people impacted

- The suitability of each party's use to the character of the locality in which it is conducted

- Extent and character of the harm to complainants

- The source's ability to prevent or avoid harm

Nuisance Odor Report by KGW News on Scribd

“If the information that we get is over a certain threshold, the next step is to inform the company and to inform the complainants that we now have a nuisance odor situation where, unless the source wants to take immediate steps to resolve the odor one way or another, we’re going to start a nuisance odor investigation,” Smith said.

During an investigation, the DEQ will send staff members out to literally smell for the odor during the time of day it was reported. The employees’ noses are vetted through an odor sensitivity test. The DEQ has them smell varying levels of a chemical substance called n-Butanol. They removed outliers who weren’t able to detect the chemical, as well as noses that were too sensitive.

If the DEQ finds enough evidence of the odor, and an investigation finds enough proof that a company is creating the nuisance odor, the DEQ can issue a fine and order the company to install pollution controls.

So far, only one investigation has gotten to that point.

The DEQ has officially launched three nuisance odor investigations, for AmeriTies, Daimler, and Riverbend Landfill in McMinnville.

After a four-year-long investigation into Daimler Trucks North America, the DEQ issued a “notice of suspected odor nuisance.”

Daimler issued a response that stated, in part:

“DTNA is willing to enter into negotiations to arrive at a Best Work Practices Agreement. However, we continue to be perplexed by the DEQ’s position because DNTA has yet to see any scientific evidence that it poses a nuisance.”

In response, DEQ is working to arrange a meeting with Daimler’s lawyer.

AmeriTies settled with the DEQ before the agency completed an investigation. The company signed an agreement and installed several new pollution controls, although The Dalles residents continue to file complaints about odors from AmeriTies.

“AmeriTies has made numerous voluntary changes at its plant, including the implementation of a new wood preservative formula to mitigate odors. The plant has been part of The Dalles for nearly a century and many of its employees have worked there for decades. As the community has grown up around it, AmeriTies remains committed to being a good neighbor and complying with all State and Federal regulations,” the company said in a statement.

The DEQ said it has demonstrated a reduction in emissions since AmeriTies signed the agreement.

“DEQ conducted air monitoring near AmeriTies before and after the change in wood preservative. The results showed a distinct decrease in naphthalene at the monitoring station nearest to Amerities after the switch,” said DEQ spokesperson Laura Gleim.

The DEQ completed its odor investigation into Riverbend Landfill and in the next few months will “develop a recommendation based on that review to present to DEQ’s Nuisance Odor Panel,” according to DEQ spokeswoman Laura Gleim.

Riverbend Landfill proposed to change the slope of part of the landfill to try to mitigate the smells. The landfill is also seeking to expand, something the DEQ has currently put on hold.

A fourth company, Vigor Industrial in North Portland, signed a “good neighbor agreement” and installed new pollution controls before an investigation could begin. Records show only two pollution complaints mentioned Vigor in 2017, after the controls were installed.

No other odor investigations are underway.

According to Smith, the DEQ’s goal is to settle, instead of spending years on an expensive and time-consuming odor investigation.

“For the DEQ to complete a complicated nuisance odor investigation, issue a penalty and an order, and the company could appeal that on multiple levels, all the time the company could be creating the odor, versus whether DEQ could sign a settlement agreement much more quickly – years quicker – you might get some relief of the situation much quicker [with a settlement],” he said.

Smith admits it’s extremely difficult to go after companies for creating bothersome smells. Even though most U.S. states have nuisance odor laws, only a few states actually enforce them.

Governor Brown’s Cleaner Air Oregon initiative passed in April, but the state has yet to determine how much the law will change emissions standards. So right now, the Nuisance Odor Strategy is a Hail Mary for residents; the last way to get the DEQ to address otherwise law-abiding polluters.

“Even though you’re in compliance with your permit, you’re not breaking any other rule, it’s possible you’re causing a nuisance odor violation. That’s essentially what the strategy does -- it’s a last resort for those kind of situations,” he said.

Not all toxics smell, and not all smells are toxic

One key metric the state’s Nuisance Odor Strategy does not consider is the toxicity of emissions coming from a business. It bases investigations solely on smell, so unhealthy emissions that don’t trigger an olfactory response are not part of the investigation.

Odors and toxic emissions are not always related. Some things can smell – such as landfills – and not technically be a toxic threat to human health. Other emissions, such as heavy metals, don’t often have a smell but can pose serious health risks.

Most of the state’s toxic industrial sites emit substances that don’t smell.

There are about 5,000 businesses in Oregon that have DEQ permits allowing them to pollute the air, water or soil up to a certain level each year. Many of those sites are listed on the federal ToxMap website, which maps facilities that release significant amounts of toxic chemicals.

Only three of Oregon’s top 10 odor complaint-generating businesses are listed on ToxMap: AmeriTies; Cascade Pacific Pulp, a paper pulp manufacturer in Halsey; and McClure Industries, which produces fire-retardant carts and laundry products in Milwaukie.

Dozens of other toxic release sites are not named in DEQ odor complaints. Residents who are concerned about the oil re-refineries APES or ORRCO in North Portland may want to turn their attention to the 24 toxic release sites located along the Oregon side of the Columbia River, between Portland International Airport and Sauvie Island.

Southeast Portland residents lived for years next to Bullseye Glass, an art glass company that was releasing heavy metals into the air. But until 2016, virtually no one knew of the threat in their backyards. It wasn’t until U.S. Forest Service scientists discovered cancer-causing heavy metals accumulating in moss nearby that the state realized dangerous emissions were being released in neighborhoods.

In addition, the state’s Nuisance Odor Strategy only goes after companies with valid DEQ permits. Businesses who aren’t big enough to need a permit, such as gas stations and diesel mechanics, often rack up odor complaints but aren’t subject to state-level scrutiny.

Several odor complaints were lodged against Marion Ag Service, a fertilizer company in Aurora, but DEQ staff told complainants there was nothing they could do.

“Thank you for your email regarding Marion Ag Services,” a DEQ employee wrote in response to a complaint in December 2016. “I understand that you’re experiencing odors at your residence that are impacting your family. Unfortunately, Marion Ag’s current production rates are below our permitting threshold and DEQ cannot conduct a nuisance odor investigation because they don’t have an air quality permit.”

Smells are fundamentally difficult to measure. What could be an overwhelming stench for one person could barely register with another. Symptoms of intense smells, such as migraines and fatigue, could be attributed to other causes.

“Identifying nuisance odors is inherently subjective and odors may be sensed as objectionable at concentrations below monitoring detection limits or practical control levels,” the DEQ says in its nuisance odor report.

Kris Cronkright says she is frustrated that she had to label her AmeriTies concerns as an odor issue in order to get the DEQ to act.

“It’s painful. It’s extremely disheartening and it basically negates any concern that anyone has,” she said. “It can be a life-threatening issue and they can just solidly look you in the eye and say, ‘No, it’s an odor issue.’ Honestly, it’s maddening and I don’t know how it’s possible they’re allowed to continue to frame it in that way.”

Cronkright, however, said she’s glad she worked for years to trigger an investigation in The Dalles.

“Before that, nobody was pushing DEQ to do anything about the industry,” she said. “At least in that way AmeriTies was having to be held more accountable. There isn’t any alternative out there.”

Cronkright is still fighting what she believes is a toxic health threat, but now she’s doing it from 25 miles away. She moved her family to Hood River last year.

“We moved because of air quality,” she said.

Interactive maps created by KGW Art Director Jeff Patterson.