Lincoln High School officials said 2007 was a breaking point. Suicide was the leading cause of death among students at the school and they knew they had to do something.

"We lost a student almost every year," said school psychologist Jim Hanson.

Principal Peyton Chapman said the school worked hard to make sure Hanson, who had been part time since 1999, could be at the school full time.

"The loss of a student just shifted all of our discussions around how did we miss this and what could we do differently," said Chapman.

Hanson implemented several research-based programs at Lincoln, including a program called dialectical behavior therapy.

According to Psychology Today, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) provides people with new skills to manage painful emotions and decrease conflict in relationships.

"We haven't lost a student since 2007. We have better prevention methods. Better suicide screening devices from the district. And we have other mental health programs for our kids that we simply didn't have in 2007," said Hanson.

The DBT class at Lincoln also involves parents. They meet once a month to discuss how they can best support their kids.

"That combination of addressing the student needs, with family needs to make the child really feel supported is crucial," said Chapman.

Rodrigo George, who has a daughter at Lincoln High School, said DBT was crucial to helping his daughter who experienced suicidal thoughts during her sophomore year.

According to the Oregon Health Authority, 18% of 11th graders they surveyed in 2017 reported seriously considering suicide in the previous year.

"When you're confronted with a hard piece of data then your attitude really shifts to think, 'OK, I need to pay more attention, be more engaged. What can I do to support her?'" George said.

Brenda Martinek, chief of student support services for Portland Public Schools, said a big shift district-wide is training teachers, coaches and other students to ask the question: Are you thinking of hurting yourself?

"There is a myth that if a student is thinking about suicide that we shouldn't ask them about it and that's not the case at all. We need to ask them. We need to ask them those questions because it will open up the conversation and validate the student's feelings, and that's when you can start providing that support and intervention for that student," said Martinek.

Rodrigo is so thankful Hanson asked his daughter if she was OK. She's doing better now but it takes a team to help keep it that way.

"It doesn't have to be you in a dark corner, faced with challenges and overwhelmed. There are tools, simple techniques and strategies, that can aid you and help you understand what you are going through," said George.

Chapman said while these programs are working, Hanson won't be full time next year due to budget cuts.

“There just aren't enough resources in our schools. We were able to have one group but having a part time psychologist just won’t be enough to keep these supports in place. And really, we should be replicating them in every school," said Chapman.

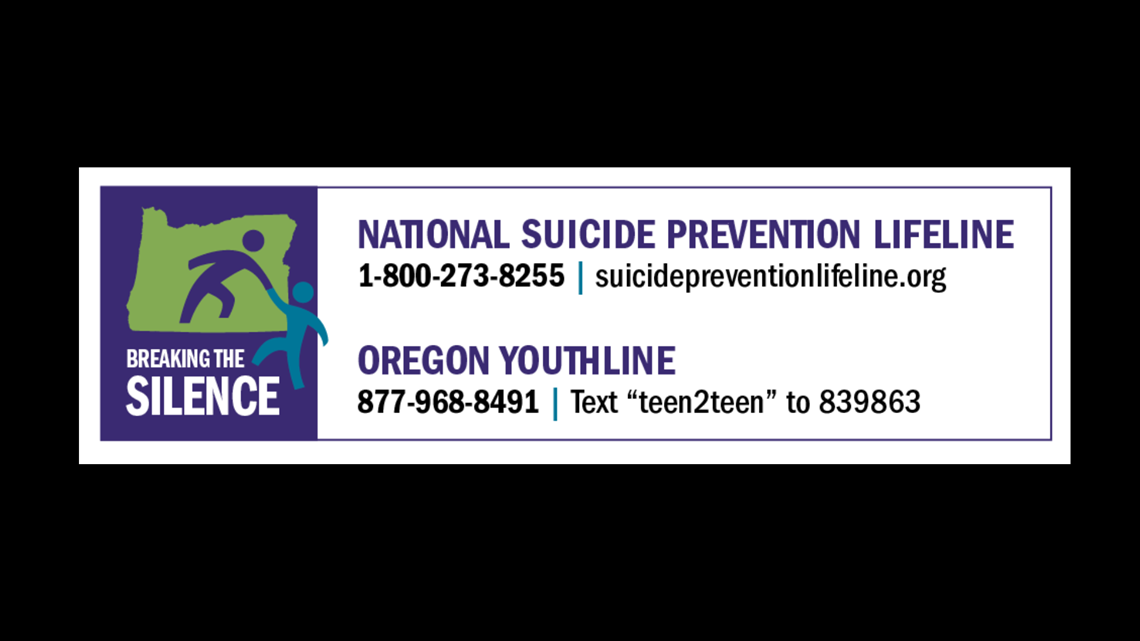

RESOURCES

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 800-273-8255. The Crisis Text Line provides free, 24/7 crisis support by text. Text 741741 to be connected to a trained counselor.

Help is available for community members struggling from a mental health crisis or suicidal thoughts. Suicide is preventable.

The Multnomah County Mental Health Call Center is available 24 hours a day at 503-988-4888.

If you or someone you know needs help with suicidal thoughts or is otherwise in an immediate mental health crisis, please visit Cascadia or call 503-963-2575. Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare has an urgent walk-in clinic, open from 7 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., 7 days a week. Payment is not necessary.

Information about the Portland Police Bureau's Behavioral Health Unit (BHU) and additional resources can be found by visiting http://portlandoregon.gov/police/bhu

Breaking the Silence

This month, newsrooms across the state are highlighting the public health crisis of death by suicide. Our goal of “Breaking the Silence” is to not only put a spotlight on a problem that claimed the lives of more than 800 Oregonians last year, but also examine research into how prevention can and does work and offer our readers, listeners and viewers resources to help if they – or those they know – are in crisis.

Most of our work will be published and broadcast April 7-14. The participating media outlets are using a common set of data and have loosely coordinated their coverage in an effort to avoid duplication and better amplify all of our work. When possible, we will promote each other’s stories, but all of them can be found on breakingthesilenceor.com