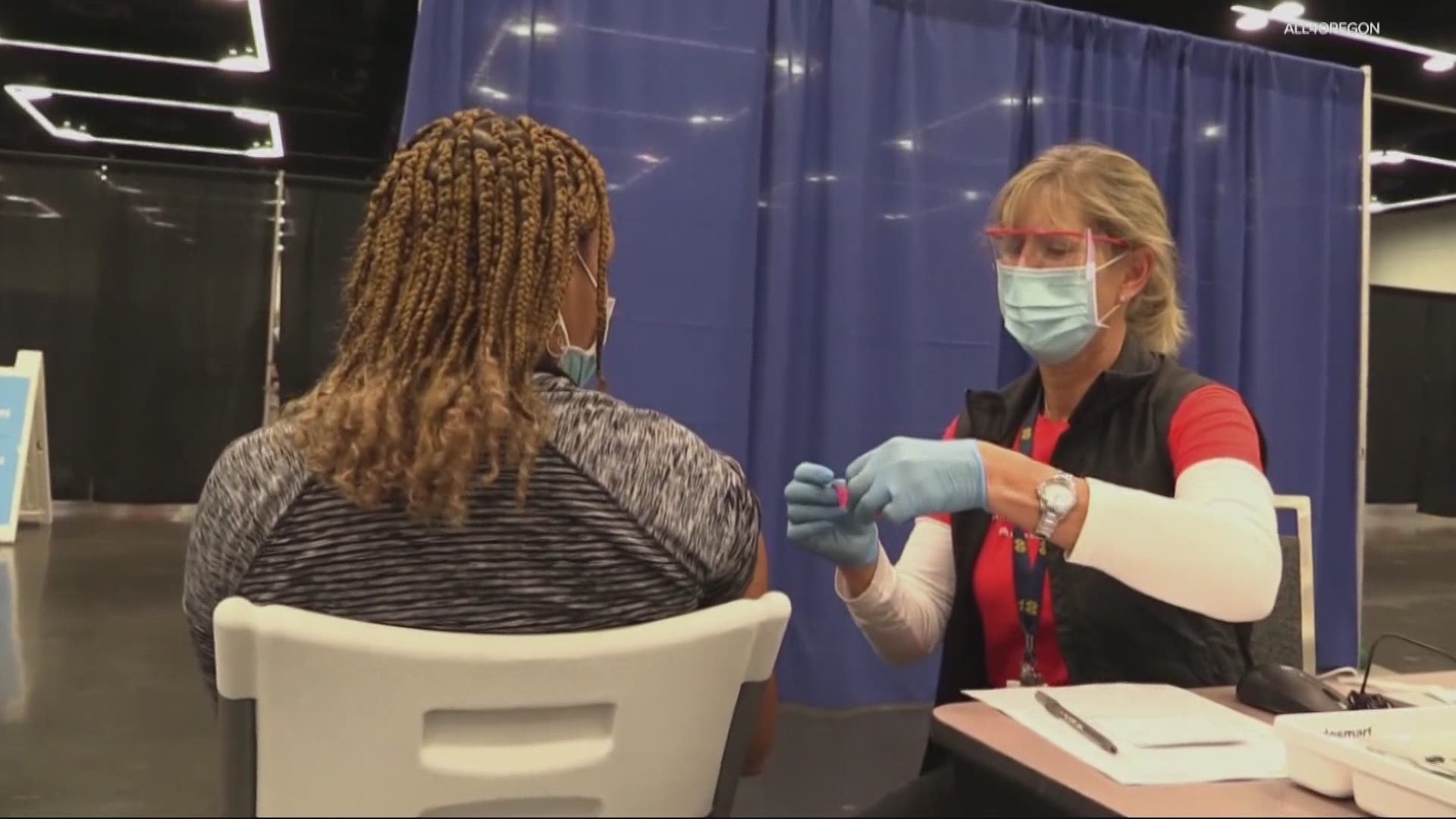

PORTLAND, Ore. — As the COVID vaccine becomes more available than ever before, the conversation has shifted from who can’t get the shot to who doesn’t want it.

Medical experts believe vaccine hesitancy could be one of the biggest hurdles in getting to herd immunity, where a large part of the population is immune to a specific disease. If enough people are resistant to COVID, the virus has nowhere to go.

“I was very hesitant,” said Wayne Hudson of Portland.

Hudson, 69, was not planning on getting the vaccine after a bad experience with the flu shot 40 years ago.

“I was afraid that this would generate that same type of reaction. My windpipe had closed up to what the doctor said was half the size of my little finger and it was a struggle to breathe. And because of that trauma, I've been very reluctant on any shots,” said Hudson.

Hudson is far from alone. Every day, the Delphi Group out of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh asks thousands of people if they got the shot, plan to get it or why they won’t. It’s the largest COVID-related survey of its kind.

“So, we've had over 2 million responses since January,” said Alex Reinhart, an associate professor at Carnegie Mellon University.

According to data, 77% of people polled are either vaccinated or plan to be, while 23% of people remain vaccine-hesitant. Oregon and Washington hesitancy numbers are on par with the national average.

Of those who are hesitant, the data shows 70% are most concerned with side effects.

“Either side-effects generally or a smaller percentage of people are worried about things like they have allergies to vaccines or other bad reactions in the past. And so, they're concerned about getting vaccinated,” said Reinhart.

When it comes to race, the study highlighted that more Black adults are willing to get the vaccine compared to a few months ago.

The data showed the percentage of vaccine-hesitant Black adults dropped from 40% to 29%, with 81% concerned about side effects.

When it comes to age, vaccine hesitancy is the largest in young people. 31% of people 18 to 24 years old said they may not get the vaccine and they cited side-effect concerns as the number one reason why.

“In broad terms, I think what's clear is that people need to know more about how the vaccine will affect them and what they can expect and how effective it is,” said Reinhart.

So how does the U.S. overcome this hesitancy problem and reach herd immunity?

Sixteen percent of vaccine-hesitant adults said they would be more likely to get the shot if the recommendation came from their own doctor.

“I think we haven't done the best job at proactively starting these conversations in that same kind of way. Most of us, you know, we were really trained to honor and respect patient autonomy,” said Dr. Cliff Coleman, associate professor of family medicine at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU).

And while Dr. Coleman still honors that choice, he's made a point to ask every patient about the COVID vaccine and if they have concerns.

Dr. Coleman will also tell patients about his own experience with the vaccine after getting it.

“I felt tired after the first dose. And then, after the second one, I developed a low-grade fever and felt, tired, and it didn't have much energy for a day,” said Dr. Coleman.

After doctors, people said they’d be more likely to get the shot if recommended by a family member or friend.

As for Hudson, he did ultimately get the vaccine and was just fine. While talking to his doctors played a role in his decision, it was someone else who convinced him to go for it: his priest.

“My priest said that it is my responsibility to my fellow Oregonians to get the shot,” said Hudson.

Hudson hopes other people talk to their doctor, friends or hear his story and do the same.

Do you have a vaccine-related story for Cristin? Email her at CallCristin@kgw.com