PORTLAND, Ore. — Hospitals in Oregon are overwhelmed by the number of COVID-19 patients they’re seeing. Hospitals in both rural and more populated areas of the state are straining to keep up with the number of people who need life-saving help and are occupying beds in intensive care units.

At Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), the day-to-day life of an ICU nurse is exhausting.

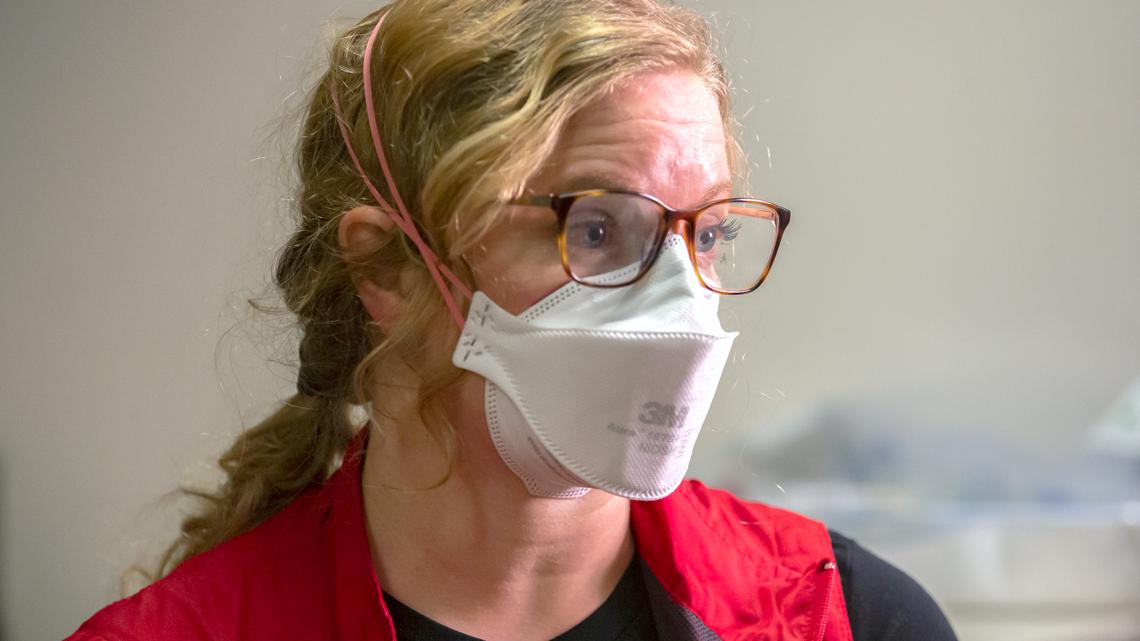

“There’s always a nurse right here ready to intervene at any moment,” said Erin Boni, an OHSU charge nurse, as she stood outside of an ICU room.

“We’re constantly assessing heartrate, blood pressure, oxygen levels. We’re monitoring the waveforms on the ventilator,” she said.

For the first time, KGW crews were allowed inside the medical ICU at OHSU to see firsthand the reality that healthcare workers are dealing with: an ICU full of COVID patients. They lie motionless in hospital beds, hooked up to machines that are keeping them alive. These patients are the sickest of the sickest.

“Every single patient on this unit right now has a breathing tube,” Boni said.

This story is part of a special KGW series, Overwhelmed: Inside Oregon's ICUs. A warning to readers: this story discusses difficult issues, including death.

"The inn is full"

ICU nurse Julie Kleese said there’s no space to physically put another patient in her unit right now. For smaller hospitals that depend on the doctors and expertise at OHSU, that's not good. OHSU is the go-to place to send patients with serious medical conditions — it's one of only two Level 1 trauma hospitals in the state equipped to handle the most serious and complicated medical issues. People from surrounding states like Alaska, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and California travel to the regional hospital for help.

“Our physicians are just being called at every opportunity,” said Kleese. She said they're getting phone calls from people asking for all kinds of help.

“Can you take this patient? Can you help us consult on this patient? This patient is 26 and dying. This patient is 21 and dying. This patient is a father of four and dying. Can you help us? Our rural partners are struggling. They’re at the limit of their capabilities and that’s when they turn to us and the inn is full,” Kleese said.

The staffing shortages many hospitals are experiencing also make Kleese’s job that much harder. The reality is that COVID patients need more care. Something seemingly as simple as flipping a patient to help their lungs inflate and increase their chance of survival is a tedious and dangerous process. In one room, four people were involved in the maneuver.

“All the lines and tubes we were talking about earlier, and making sure not a single one of them gets caught or dislodged accidentally during that flip,” said Boni.

Kleese said this is the most COVID-positive patients they’ve ever seen in the hospital. Right now, nurses are taking on extra shifts to keep up with the workload. They’re working themselves into the ground, all to help their patients, almost all of whom chose not to get the vaccine. While KGW crews were there, only one patient out of 14 had been vaccinated.

The reality of being hospitalized with COVID

“I don’t think people have an inkling of the amount of suffering that you will experience being sick with COVID. It is extremely painful. Being critically ill is a very traumatizing experience. It is confusing. It's scary. You’re alone with strangers. You don’t recognize their voices. You lose your free will being in the hospital,” said Kleese.

That suffering isn’t just limited to the people in these hospital beds. It extends to their family.

“If they get to see you, whether it’s on video camera or in person, they will see you suffer greatly. It’s really unnecessary. It’s totally avoidable. I think that’s the most heartbreaking part of it,” Kleese said.

Because it’s too risky to have family members visit COVID-19 patients, in their time of death COVID patients are often alone, save for a nurse at their bedside who becomes their family in the moment. It’s a near-impossible and heart-wrenching task.

“What can you say?” said Kleese as she held back tears.

“I know the depth I would feel if I couldn’t be with my loved one as they died. So I take the responsibility very seriously to love that person as if they were my own family member and provide them with a death that’s dignified and honorable as much as possible in an ICU that is sterile and cold and unforgiving,” said Kleese.

Overwhelmed: Inside OHSU's ICU

A firsthand account

Walking through the ICU as someone outside of the medical field, the scene is jarring.

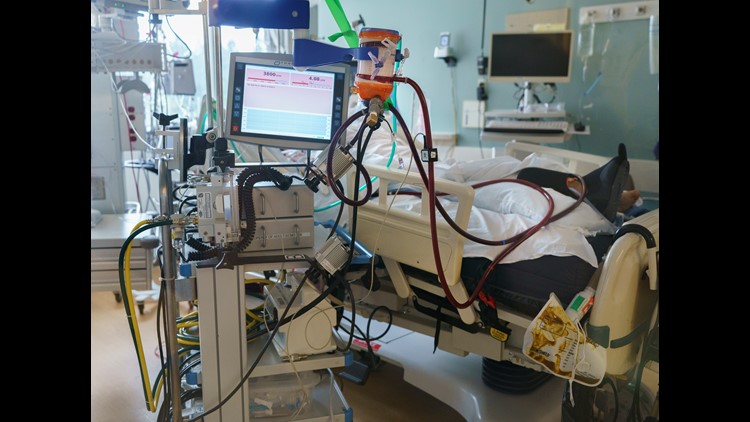

A woman in her 20s lies in bed, incoherent, hooked up to many tubes of different sizes. Some are distributing medication, others are used to drain urine or stool. More tubes are connected to an ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) machine. Those tubes transfer roughly four to five liters of blood out of the body every minute, oxygenate it, then put it right back in. Kleese said an ECMO machine is the highest form of a life-support they can provide.

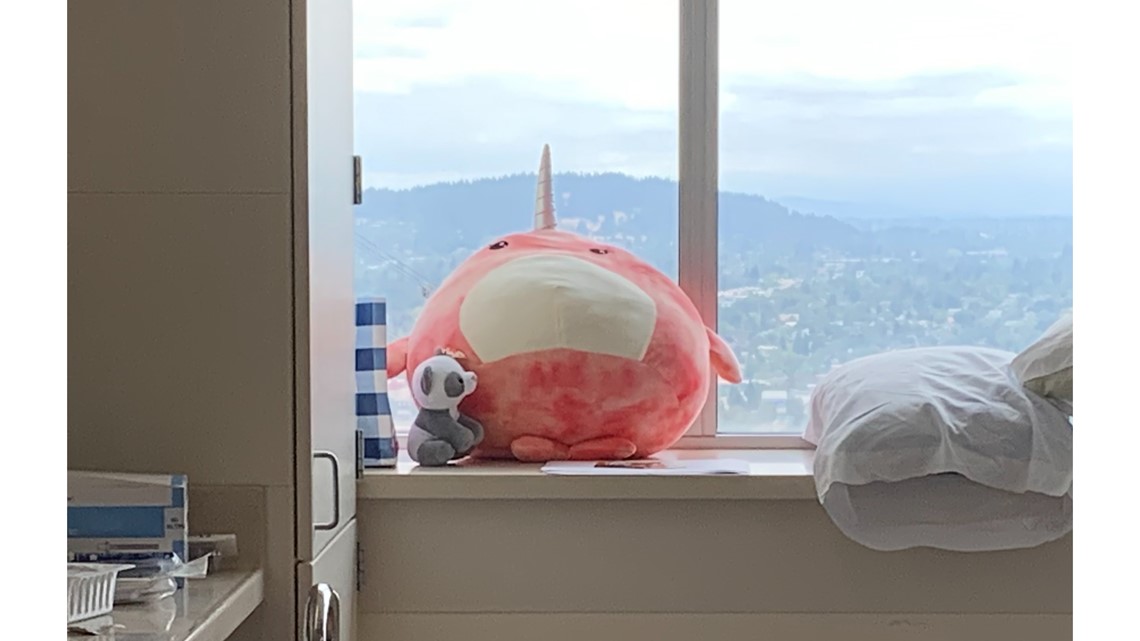

In the corner of the young woman’s room sit brightly-colored stuffed animals from loved ones who can’t be there themselves.

Not far down the hallway, photos of people smiling are taped to the wall in another room. The man seen in many of the photos is smiling broadly with what appears to be family members and friends. The jovial face seen in the photographs is now slack as he lays motionless feet away in his hospital bed.

Boni said they're treating maybe one patient in their 70s. The rest are in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s.

“We see plenty of people who are fully functional, no blaring underlying conditions who did not think they were at risk of severe impacts from COVID-19 and they are here fighting for their lives,” said Boni.

She says what breaks her heart are the conversations she has with family members who lament the fact that they and their now-hospitalized loved one didn’t get the vaccine.

“They had just heard so much misinformation that they just didn’t know what to think. So either they didn’t think they were at risk or they were really worried that COVID vaccine side effects were going to impact them," said Boni. "They were more worried about the vaccine side effects, which we know, we just know from all the data we have, is that your risk if you get COVID is so much higher than your risk of side effects from a vaccine. That data’s out there and I just wish people could hear it. If you’re worried about side effects from the vaccine itself, your risks of what could happen to you or your loved one if you do not get vaccinated are astronomically higher."

Frustration among healthcare workers

The frustration around people who refuse to get the vaccine keeps growing.

“I think people are leaving. People are getting burnt out. People feel so frustrated knowing they are caring for patients. Now it’s a preventable illness. They’ve given so much because they’ve volunteered to work extra. At some point, you’re so tired and you realize, like, ‘I can’t live my normal life and I can’t be present in my home life and also do this work,” said Boni.

That means some healthcare workers have quit rather than possibly destroy their or their family’s mental and physical health. Other healthcare workers have said some have decided to retire early.

“I would be lying if I say there isn’t anger for people who are vaccine deniers, or believe conspiracy theories, or have a lot of misguided information about this and then end up in our hospital suffering and dying. Sometimes they will say 'I was wrong. When can I get the vaccine?' Sometimes they’ll deny it to their dying breath,” Kleese said.

For ICU nurse Emily Williams, the situation is well beyond just frustrating.

“I had to call over to the pediatric ICU one day to ask for a beanie baby to give to a 12-year-old while I turned off the [life] support and her dad died. I don’t want to do that, you know? You’re holding the hand of a pregnant wife whose husband is fighting for his life. Who wants to do that? It’s overwhelming and it just keeps happening and it doesn’t stop. There is no end. We see no end. What do you do?” said ICU nurse Emily Williams.

She has seen a lot as an ICU nurse and has even cared for people after a mass shooting, but she said what she’s encountered during the pandemic — especially recently — is on another level. Williams said people stay in the ICU for weeks if not months, meaning that bed space can’t be used for anyone else who may need it. If this continues, Williams said, people won’t get the basic medical help they need.

“If we are full of COVID, where do these people think the other people are going to go? We don’t have hospitals for non-COVID. We don’t have magical places for people to go,” Williams said.

In addition, recovery from COVID is a long road. She said it can be a year of recovery in a rehabilitation center with potential complications in the future that cause patients to bounce in and out of the hospital with infections.

“It kind of feels like the world just gaslighting you, like they don’t believe your experience. Why don’t they believe what we are experiencing and what we are telling them? It’s just so frustrating,” she said.

"It could have been prevented."

Kristen Roach, an ICU nurse who also works at OHSU, said she wishes people thought of others more when it comes to getting the vaccine.

“I wish it was more community focused. I wish we could focus more on, 'If I got vaccinated then I would be protecting my grandmother,' or 'I would be protecting these other people I care about.' I just think we’ve become so individualized that it’s really done a disservice to our country,” said Roach.

“I think we really just need more people to get vaccinated. I don’t see another way out of this,” Roach said.

Every ICU nurse and doctor we’ve spoken to has reiterated that at this point, much of the death and serious illness is preventable.

“It’s hard not feel like this is the epitome of privilege and in this country we have the privilege to get this vaccine. Globally, people would do anything for this vaccine and they don’t even get this chance,” said ICU nurse Sara “Mo” Mohkami, who has unvaccinated family in Iran.

“It’s devastating. It’s really heartbreaking knowing that people are fighting for their lives and it could have been prevented,” said Boni.

At the end of her day, like many of her colleagues, Boni doesn’t have much more to give.

“[I’m] often exhausted and defeated and sad, if I’m honest,” said Boni.

But despite their immense fatigue, for now, they keep going.

“It’s been a struggle to show up every day but we’ve been here and my team has been here. I love being a nurse […] but this has been really hard and I’m really proud that I’ve continued to show up,” Roach said.

“I think if anything has shown us during this last year and a half is just how resilient we are and how we look out for each other,” said Mohkami.

The plea from so many nurses and healthcare workers is clear.

“This doesn’t have to happen to anybody anymore. So if you’re able to get the vaccine, get it," said Boni.