PORTLAND, Ore. — An Oregon Health and Science University study released in December suggested that COVID-19 breakthrough infections — an infection after a person has been vaccinated — can prompt an extremely robust immune response, giving the person so-called 'super immunity' once they recover.

Now a new study suggests the reverse could also be true — infection followed by vaccination could trigger a roughly equal level of enhanced immune protection, according to a news release from OHSU. The new study was published Tuesday in the journal Science Immunology.

The order of the two events appears to make no difference, according Dr. Fikadu Tafesse, assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the OHSU School of Medicine and one of the co-authors of the study.

"In either case, you will get a really, really robust immune response — amazingly high," he said in a statement.

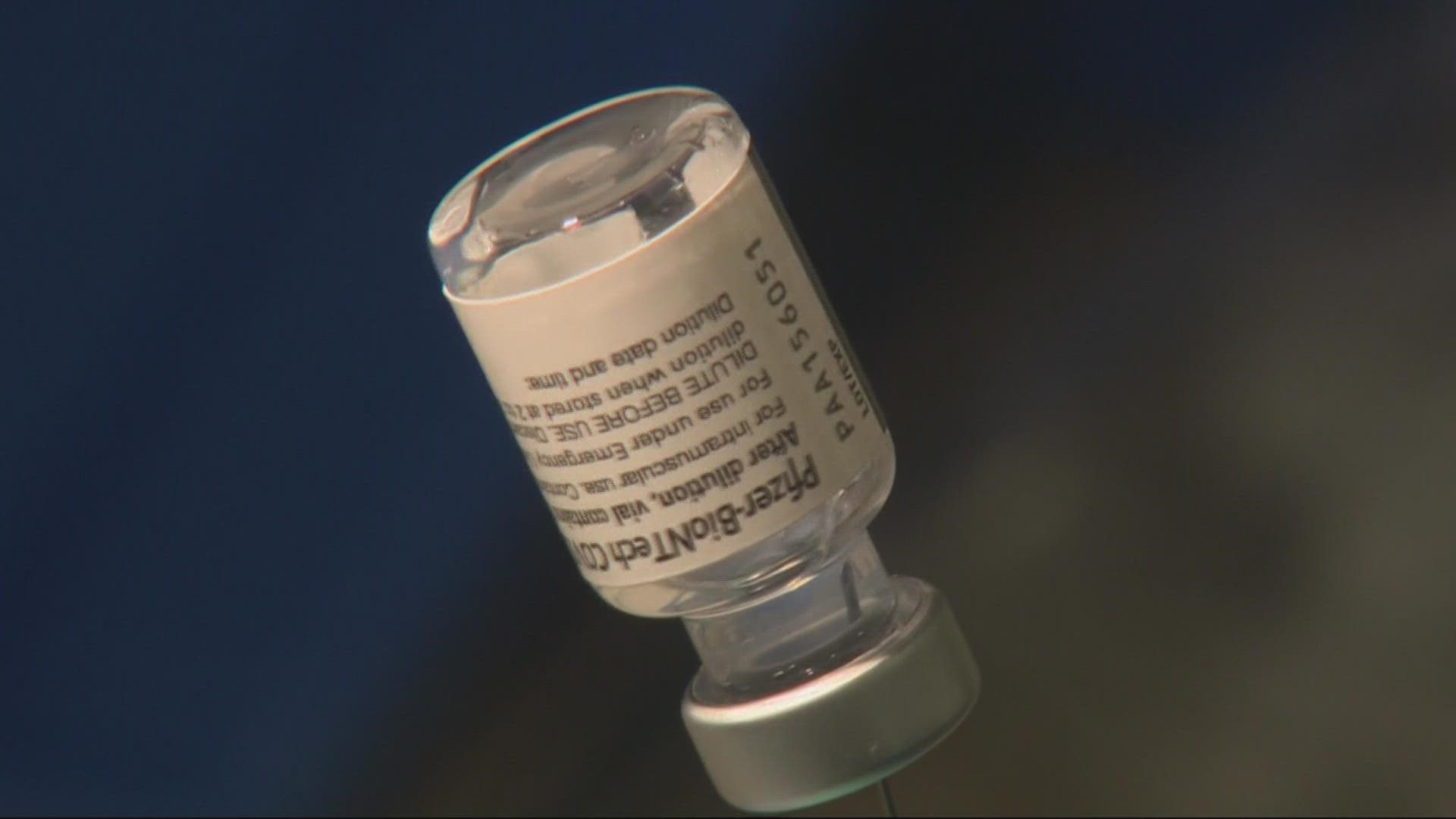

The study involved 104 people, all OHSU employees, who were vaccinated with the Pfizer vaccine and then divided into groups based on whether they had been infected before or after vaccination, or had never been infected.

Controlling for other factors like age, sex and time between vaccination and infection, the researchers drew blood from each participant and exposed the samples to three live variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, working inside a Biosafety Level 3 lab at OHSU's campus.

"We found that the antibodies in your blood, following the combination, were about 10 times more potent than the antibodies in your blood if you just have a vaccination," said Dr. Bill Messer, assistant professor of molecular microbiology and immunology and another of the study's co-authors.

The study was conducted before the emergence of the highly contagious omicron variant, which has been the main driver of Oregon's skyrocketing daily COVID case rates in recent weeks.

Still, the researchers said they expected the hybrid immune responses would be similar for an omicron infection, according to the news release.

"The likelihood of getting breakthrough infections is high because there is so much virus around us right now," Tafesse said. "But we position ourselves better by getting vaccinated. And if the virus comes, we’ll get a milder case and end up with this super immunity."

The news release noted that prior research has suggested that the level of immune produced by natural infections alone — meaning one or more infections in people who have not been vaccinated — is less consistent.

“I can guarantee that such immunity will be variable, with some people getting equivalent immunity to vaccination, but most will not," Messer said. “And there is no way, short of laboratory testing, to know who gets what immunity. Vaccination makes it much more likely to be assured of a good immune response.”