Social distancing is a new phrase, but the practice itself used to be rather common in the U.S.

When whooping cough, scarlet fever or measles showed up in a community early in the 20th century, affected children typically were kept at home for a few weeks. Sometimes this was formalized, with the local health department tacking signs to front doors stating: “QUARANTINED.”

At the time, epidemic meningitis killed up to 25 percent of children who contracted it. Fifteen percent of people hit with polio ended up seriously crippled, with about 5 percent dying.

Yet whatever viruses were swirling around, and however deadly or debilitating they were, life -- and commerce -- carried on. After all, an outbreak of one sort of another happened almost every season, almost everywhere. They were expected.

These local epidemics worried people but the fear was limited, says Eleanor Crick, a 96-year-old retired nurse who lives in Milwaukie.

“If someone was sick, you took care of them,” she says. “People didn’t know any different.”

In the 1940s, she recalls, the Red Cross sent her to Alabama and Tennessee during a polio outbreak in the South. She helped patients who were encased in iron-lung machines, “sticking my hands and arms through the portholes.”

These full-body pulmotors were big and unwieldy, something you might expect to show up in a gothic-horror novel. But they were part of normal life in towns and cities across the country.

In 1953, a doctor with the New York State Rehabilitation Hospital told The American Weekly that there was no reason to pull kids from school when polio popped up.

“By the time an outbreak is underway the chances are your child already has been exposed,” Dr. Kenneth S. Landauer said. “It is best to keep him and yourself calm, but be alert for symptoms.”

He insisted that other members of the household could come and go as they pleased while the exposed person recovered.

“Because quarantine is not effective,” he stated.

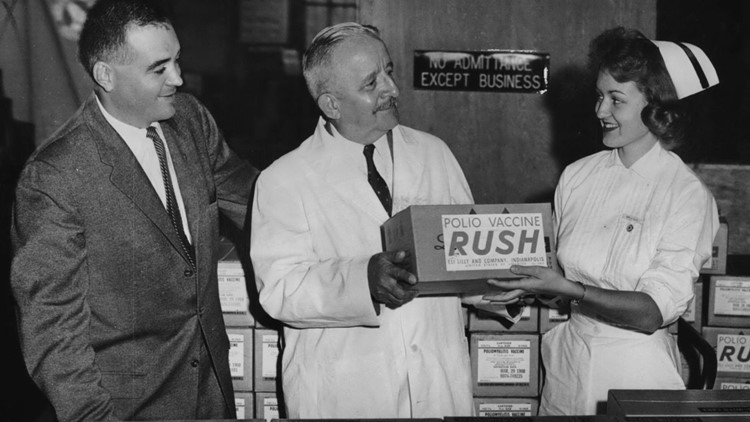

The large-scale rollout of the polio vaccine began in 1954, the year after Dr. Landauer gave his nationally distributed advice about the disease. The incidence of polio in the U.S. quickly plummeted from 18 cases per 100,000 people to fewer than 2 per 100,000. In 1952, there were 57,000 cases of polio in the U.S. Forty years later, the disease was considered eradicated in the Western Hemisphere.

Jonas Salk’s famous vaccine was but one of many that changed modern life in the second half of the last century. Diseases that had been persistent scourges throughout U.S. history were entirely wiped out. Americans began to think of deadly epidemics as tragedies that happened only to other people in far-off places.

Now, comfortably into the 21st century, Americans are quarantining themselves to slow the novel coronavirus, a national public-health effort without precedent in the country.

People are afraid for their health -- and for good reason. The worst-case scenario envisioned by public-health officials would see a million or more Americans killed by the pandemic.

People also are afraid, for good reason, for the health of the economy, as consumers lock themselves in their homes and stores shut down. (A bad economy can be as deadly as a vicious virus: During the Great Depression, suicides dramatically spiked.)

But even if the massive attempt to blunt the pandemic succeeds, thus keeping hospitals from being overwhelmed, the coronavirus will continue to circulate. A vaccine is unlikely to be available for at least 18 months.

That means Americans have to figure out how to live with the virus while still leading relatively normal lives. Crick, for one, takes an old-school approach to the current crisis. She believes people today can learn something from those who went through annual local epidemics back in the 20th century.

Vigorous hand washing, as public-health officials have advised, is important, yes. But it’s only a start, she says.

“I never saw a messy house,” she recalls of her long-ago days as a nurse making the rounds during polio outbreaks. “You could eat in people’s barns, they were so clean. People were fastidious.

“You be careful, and you go on.”

-- Douglas Perry

This article was originally published by [media organization name here], one of more than a dozen news organizations throughout the state sharing their coverage of the novel coronavirus outbreak to help inform Oregonians about this evolving heath issue.