CORVALLIS, Ore. — The COVID-19 pandemic has changed lives across the world since it started over two years ago. Now, U.S. health officials are suggesting a big coronavirus surge could infect 100 million Americans this coming fall and winter.

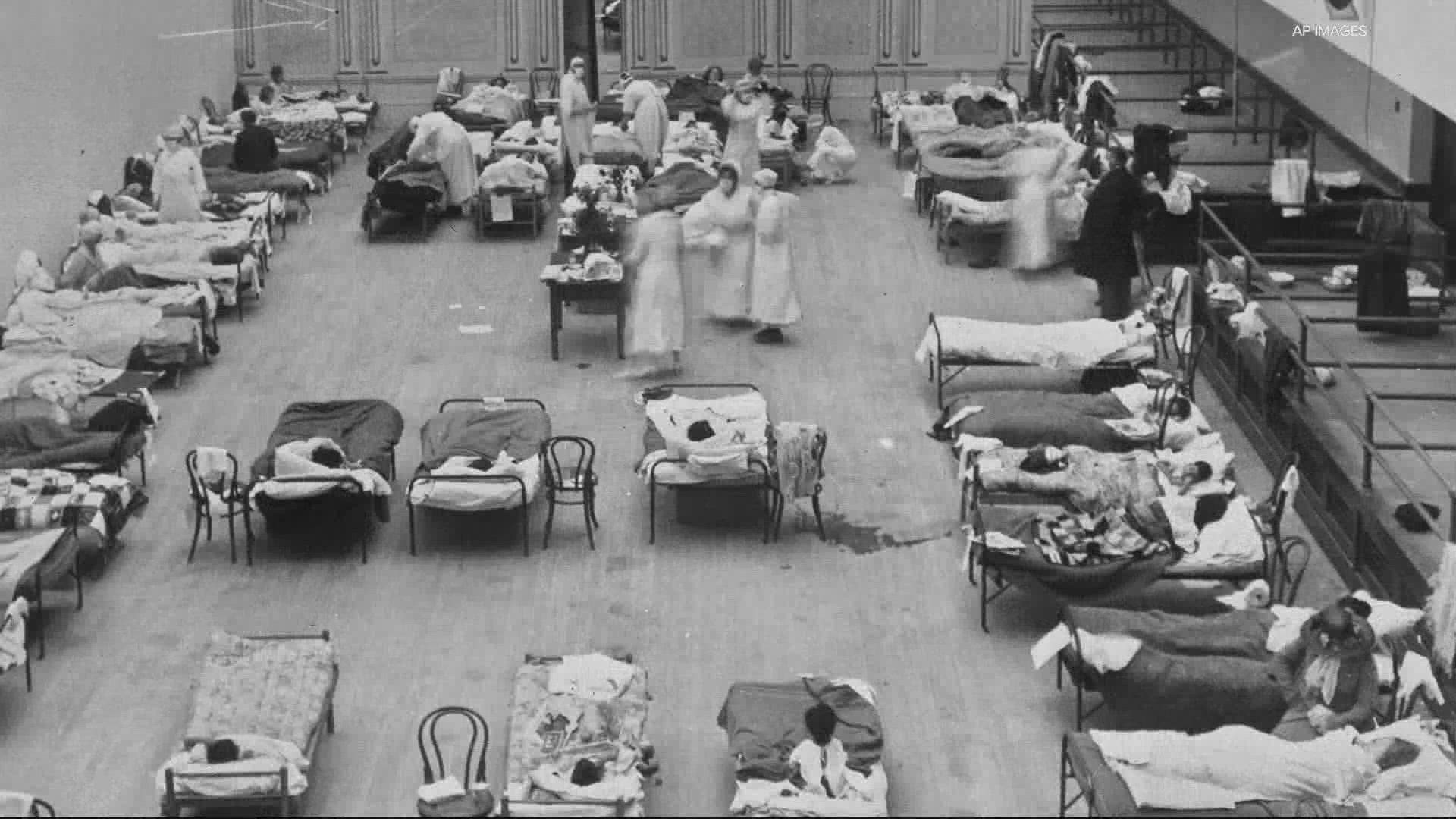

That's hard news to hear, but it's not surprising for people who've studied the 1918 flu pandemic, which claimed the lives of nearly 700,000 Americans.

A team of health and history experts recently published an article through Cambridge University Press that compares the COVID-19 pandemic to that bleak time in history about a century earlier.

The article answers some critical questions about pandemic in general.

"How do pandemics end, do they ever end and what are the aftermaths of the pandemic can we see that historically? What should we be able to expect or what kinds of questions should we be asking ourselves,” said Christopher McKnight Nichols, history professor and director of Oregon State University’s Center for Humanities.

Nichols and other experts who co-authored the report see many similarities between the influenza pandemic of the past and our current pandemic.

First, both diseases are very likely here to stay and continue to take lives.

“The short answer is no, the pandemic isn't over. And the long answer: the same thing with the flu, the flu's still with us 100 years later. COVID will probably still be with us in 100 years

Nichols knows that after two-plus years, COVID fatigue is real and understandable. But he is concerned that, like in the early 1900s, people ignoring the facts and deciding it's over will make us less safe.

“One of the things you see in the historical record is mayors and other officials hoping the pandemic is over and yanking off measures, even when they didn't have vaccines and other things. And then you have higher surges and a second peak that's worse.”

Some of the methods of fighting disease haven't changed much.

In 1918, Americans were quarantining, using similar hygiene practices and physical distancing.

A key difference between now and then is that efforts to develop effective vaccines did not work in the early 1900s, whereas there were three COVID vaccines available less than one year into this pandemic.

Although modern medicine and public health infrastructure have both improved significantly, Nichols said science is not the final decider for determining when a pandemic is over.

“From my perspective as a historian, the end of a pandemic is political or psychological. It isn't biological or epidemiological, and that's something that we could get across to people almost regardless of their politics.

So, learning from the past essentially means realizing it's up to the public to responsibly deal with an infectious disease that will likely be present for many years to come.

“We need to figure out how to take onboard those lessons and make better judgments moving forward, which may mean restricting our lives a bit; and I think we need to be comfortable with that.”

Nichols hopes the article will be used and shared by teachers to help the next generation learn from the past.