GRAND RONDE, Ore. —

Standing in the entryway to the new health and wellness clinic on the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde reservation, Kelly Rowe can’t help but think about all the people it will serve.

The building, which will serve to augment the health care services offered at the tribe’s other health facility, is nearly complete, with a grand opening scheduled in the coming days.

For Rowe, the executive director of health services for the tribe, the building represents more than just a new space to treat tribal members.

“Every time they walk through those doors, there is a sense of being here that belongs to every one of us,” she said, noting that the design incorporates nods to tribal culture. “This is their clinic. This isn’t just a clinic that belongs to the tribe; it’s the tribal member’s clinic, and culture is medicine.”

The tribe teamed up with Energy Trust of Oregon, a nonprofit that works to help improve efficiency, to make sure the health center was outfitted with the latest in environmentally friendly technology.

“Some of the design choices that were made to increase efficiency involve upgraded lighting; they put in sun tunnels and solar panels on the roof, as well as ventilation systems and also individual climate-controlled zoned rooms,” said Scott Leonard, program manager with Energy Trust.

Ryan Webb, engineering and planning manager with the tribe, said it was a priority to keep the environmental footprint of the building small, even as its physical footprint expanded.

“The tribe is very committed to being the stewards of the land like they’ve always been,” he said.

When the pandemic struck, it quickly became clear the tribe was lacking the infrastructure to serve its members. The old clinic — which offers full medical and dental services — lacked a way to provide testing while keeping people separate. The new wellness center solves that problem.

It’s heating and ventilation system is divided into zones, which will help in situations where people need to quarantine from one another.

“During a potential pandemic or airborne disease situation, we can actually shut it down and bring in outside air into the building,” Webb said.

Along with six examination rooms and two rooms for dental services, the center also features a large community room with a demonstration kitchen. That room is outfitted with upgraded audio and visual technology so cooking demos can be livestreamed to tribal members in their homes on the reservation, around the state and even around the world.

“It’s not just a focus-western medicine,” Webb said, “but really how nutritional health or cultural practice can heal people as well.”

Outside on the expansive patio, a fish pit was installed to showcase traditional preparation of salmon, a food of huge cultural significance to the tribes.

“We can provide health and wellness in a culturally sensitive way to the community and really help to lift everybody up to be healthier in who they are and what they do,” Webb said.

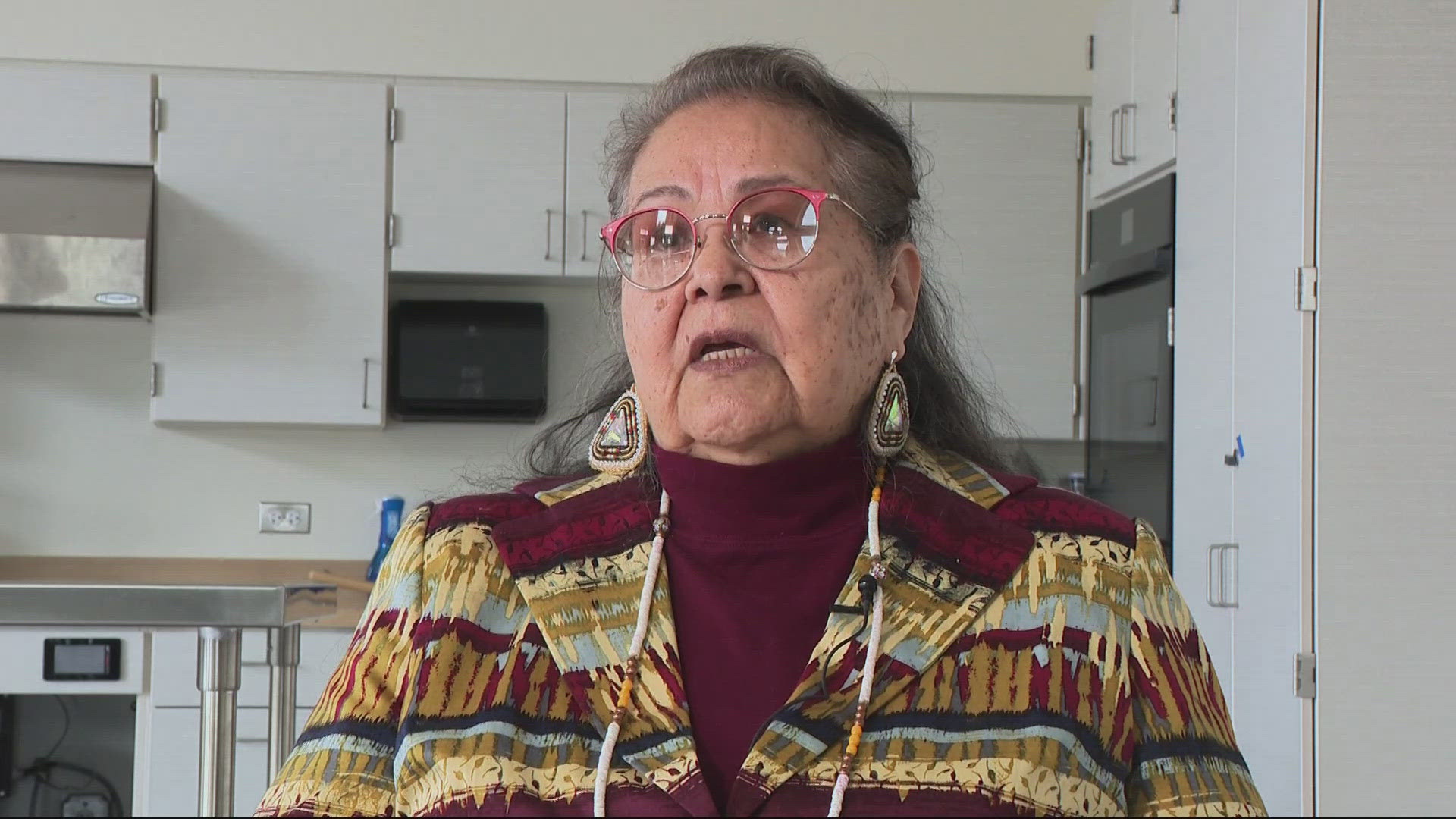

Cheryle Kennedy, chairwoman of the tribal council, said history has taught them that if the tribes need something done, they often have to do it themselves.

In the 1850s, the tribes were forced off their ancestral lands in exchange for recognition from the federal government. But in 1954, the government revoked that recognition in a process called termination.

“That was very difficult for most of the families because the land was taken,” Kennedy said. “Termination meant they came in and stripped you of all the land you had, any service that was provided to you.”

That left tribal members needing to travel long distances for healthcare.

“Services were nonexistent here, so if people wanted healthcare, they had to figure out how to travel to get there,” Kennedy said. “The clinic that serviced Grand Ronde at that time was located in Salem.”

The tribes regained recognition in 1983, around the same time Kennedy joined leadership and began pursuing healthcare services for tribal members.

The new clinic was the natural next step in allowing the tribe to provide for its members.

“This is so important," Kennedy said. “(The clinic) is where our members can come, and we no longer have to fear that we’re the orphaned child, that we’re not going to receive the services that other Americans and Oregonians receive.”

And there are nods to tribal culture throughout the wellness center, Rowe said.

“When you come into the community room, you’re going to see the big, round window. It represents a couple things,” said Rowe. "It's a representation of the medicine wheel. It also mimics our plank house. It’s the round doorway into the plank house.”

The wood siding also holds significance, salvaged from tribal lands that burned in the 2020 Labor Day wildfires.

“We tried to use everything we could from the tribe, to source from within and use things that were important to us as a tribe,” Rowe said.

Next to the fish pit on the patio, the concrete is stamped with traditional depictions of salmon.

“We have the salmon stamped outside and that’s to show it's not just our first food — it's our relationship to the water, it's our relationship to the fish, how important it is for us to be honoring that every time we walk out on that patio,” Rowe said. “We’re going to see that and it’s like, 'Yes, we have that; that’s part of us.'”