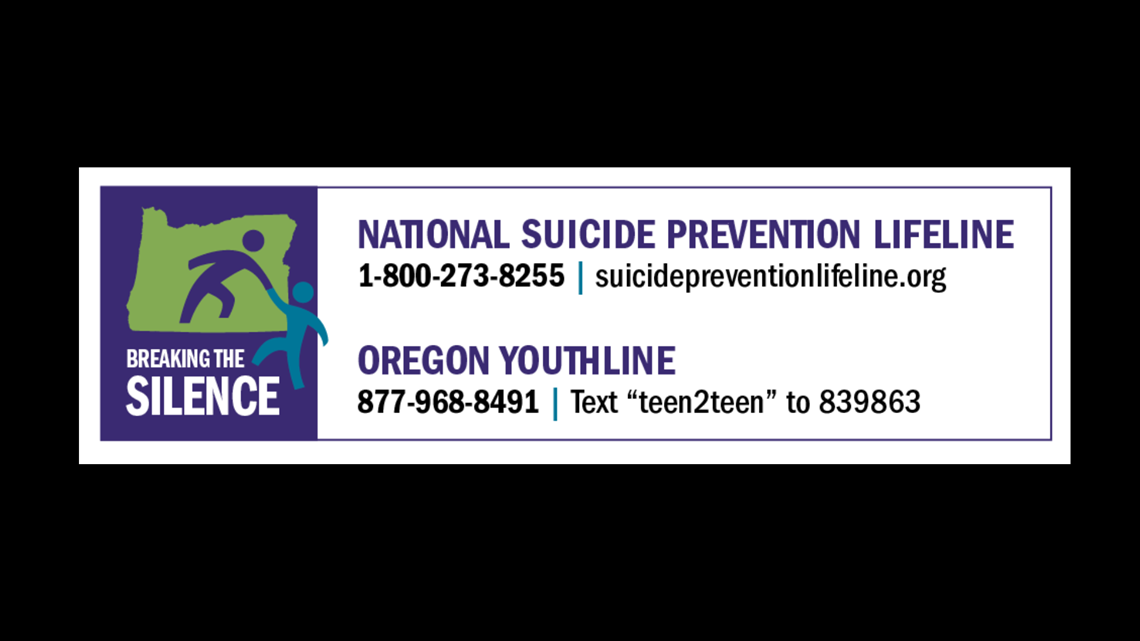

Editor’s note: This month, newsrooms across the state are highlighting the public health crisis of death by suicide. Our goal of “Breaking the Silence” is to not only put a spotlight on a problem that claimed the lives of more than 800 Oregonians last year, but also examine research into how prevention can and does work and offer our readers, listeners and viewers resources to help if they – or those they know – are in crisis.

Most of our work will be published and broadcast April 7-14. The participating media outlets are using a common set of data and have loosely coordinated their coverage in an effort to avoid duplication and better amplify all of our work. When possible, we will promote each other’s stories, but all of them can be found on breakingthesilenceor.com

SALEM, Ore. -- Salem Police Officer Joe Miller knows he can't save everyone, whether it's a woman holding a knife to her neck, an armed man ready to drive his truck off a cliff, or a young person ingesting poison.

His job is to give them a chance.

Miller responds to mental health calls with the department's Behavioral Health Unit. His partner is a mental health professional with a master's in counseling. Their goal is to de-escalate the situation and get the individual help.

Positive outcomes are seldom reported. Salem Police doesn't keep statistics on saves. But it's not hyperbole to say interactions with individuals in suicidal crisis happen at least weekly, if not more often.

"We're getting better at intervening," Miller said. "But despite the best care, some are going to complete, they are not going to survive. I know that's on the table."

But who intervenes when a law enforcement officer is in crisis? Who gives them a chance when they're suffering from anxiety and depression or having suicidal thoughts?

Marion and Polk county agencies often recognize when one of their own is in crisis. They've prevented some from committing suicide, but they've also missed warning signs in others.

Oregon State Police lost a sergeant a few years ago, and no one saw it coming. Co-workers, even family members, rarely do.

That's what makes suicide so complicated. There is no single cause, but it's often linked to mental health conditions and stressful life experiences.

First responders, including firefighters, paramedics, even dispatchers, are at risk of suicide because of their everyday exposure to trauma. They witness more in a few months than most people in a lifetime, and it can affect their mental health.

Post-traumatic stress disorder and depression rates, for example, have been found to be as much as five times higher among police officers and firefighters than among civilians.

Both can increase suicide risk.

Studies continue to show members of both professions are more likely to kill themselves than be killed in the line of duty, which would include everything from being fatally shot, dying in a car accident, or from injuries sustained in a fire.

In 2017, according to the Ruderman Family Foundation, at least 140 police officers and 103 firefighters died by suicide compared to 129 police officers and 93 firefighters in the line of duty.

On top of that, experts believe suicide deaths are under-counted, with many classified as accidental or undetermined. The Firefighter Behavioral Health Alliance estimates less than half of firefighter suicides are reported.

"We're working off limited data," said Dr. Robert Douglas, founder and director of the National Police Suicide Foundation. "We don't have 18,000 agencies opening their books and saying, 'We have had so many suicides.' "

Changing culture, overcoming stigma

Tracking first-responder suicides is difficult. It's often not reported, there typically are no witnesses, and data is collected from multiple sources.

Suicides in Oregon are tracked through the Violent Death Reporting System under the Public Health Division of Oregon Health Authority. But the data is outdated.

The most recent report, "Suicides in Oregon: Trends and Associated Factors," breaks it down by demographic characteristics such as age and occupation.

Among people aged 18 to 64 who died by suicide in Oregon between 2003 and 2012, 89 were police officers and firefighters. During that same period, 33 police officers and firefighters died in the line of duty, according to a review of records for Oregon's fallen memorials.

Officers and firefighters who take their own lives are not eligible for inclusion on state or national memorials. Only the names of those killed in the line of duty are etched on the solemn granite walls.

Reducing the stigma and advocating for recognition of law enforcement officers who suffer emotional injuries on the job and are lost to suicide are the battle cries of the Massachusetts-based nonprofit Blue H.E.L.P.

The organization reports 460 known officer suicides from Jan. 1, 2016 through Dec. 31, 2018. Every state experienced at least one. California had a nation-high 48. Oregon was among the least-impacted states with four documented suicides in the three-year period.

Even so, local agencies in Marion and Polk counties are proactive when it comes to suicide prevention. They've implemented Critical Incident Response Teams (CIRT) and other peer-led programs to promote mental and emotional health in their first responders.

Not every first responder experiences an increased risk of suicide, but if they do, there is more help available than in the past.

New recruits are learning to recognize the signs in themselves and being taught it's OK to seek assistance after a crisis.

Shame and stigma are still barriers, as they are with suicide among any population. But it's compounded in professions that prioritize bravery and toughness.

"The culture in law enforcement when I first started back in 1986 was essentially, if you can't take the heat, get out of the kitchen," Oregon State Police Lt. Steve Duvall said. "If you have difficulty dealing with the death of people, working on crime scenes where there are body parts, organs, and blood, you need to find another career."

Duvall is a 33-year veteran. CIRT teams and peer support programs were unheard of when he was sworn in. Coping with stress in those days typically meant a bunch of cops getting together at a local bar and drinking to forget whatever traumatic event they faced.

Marion County Undersheriff Troy Clausen, a 28-year law enforcement veteran, referred to it as "beer counseling."

But those informal debriefings only added to mounting problems.

Alcohol consumption among first responders is higher than that of the general population, and alcohol dependence is a major risk factor for suicide.

Alcohol abuse is involved in more than 85 percent of police suicides, according to the National Police Suicide Foundation.

The "suck it up and move on" culture has changed, but most agree there's still room for improvement.

Seasoned veterans like Duvall and Clausen are leading the way to further efforts within their own agencies and across the state.

Clausen is a pioneer in the development of crisis outreach and peer support teams for the Marion County Sheriff's Office. He's also co-chair of the Officer Wellness Statewide Task Force, which helped pave the way for the introduction of two bills this legislative session.

Senate Bill 423 would mandate all law enforcement agencies do pre-employment psychological screening to determine a person's fitness to serve. SB 424 would require agencies to establish a mental health wellness policy.

Duvall has been the commander of OSP's CIRT team since 2015. He volunteered for the position. Peer-to-peer counselors are an important resource for those reluctant to use professional mental health services.

Granting confidentiality is the key, Duvall said.

"We talk very bluntly and plainly to people who have been involved in a traumatic event," he said. "There is no shame in being overwhelmed by the things we have to deal with and realizing if you can't handle it yourself, you can reach out to a peer, and in some cases professional help."

OSP, like most local agencies, partners with volunteer chaplains and mental health professionals.

Clausen has presented "Emotional Survival Training" to numerous agencies and seen a shift in attitude when it comes to asking for help. Ninety percent of officers recently answered yes when asked on a questionnaire if he or she would be willing to seek help from a mental health professional if needed.

"Five to 10 years ago, you wouldn't have seen that," Clausen said. "Most would have thought, 'Not if it's going to cost me my career.' "

Teaching resiliency, stress first aid

For new officers, the stigma is being chiseled away before they put on the uniform and badge.

Recruits are getting a block of training on resiliency and stress first aid as part of basic police training at the Oregon Department of Public Safety Standards and Training (DPSST).

"They make clear that seeking assistance for emotional health issues and mental health support no longer has the negative stigma that it used to," Duvall said. "That has been a phenomenal change in law enforcement training."

Linda Maddy, a licensed clinical social worker, is co-coordinator of the Behavioral Health Program at the Center for Policing Excellence at DPSST, where officer wellness parallels officer survival.

She arrived three years ago with a background in veterans' outreach at the Portland VA Medical Center, where PTSD and suicide get more attention.

Maddy said DPSST has been open to restructuring programming and adding curriculum, recognizing the cumulative stress over a career.

According to Blue H.E.L.P. data, 37 percent of law enforcement suicides between 2016 and 2018 were among the 40-49 age group, averaging 17 years of service.

New recruits at the Oregon police academy now get nine hours of training in a course called Resiliency. They are introduced to the topics of vicarious trauma, triggers and stress reduction strategies. They are instructed to build a strong support system and create a resource directory.

"You're a human being when you come into this, and you don't lose that status," is what Maddy and other instructors tell them. "It's OK to have these reactions. It's normal. When you're exposed to these things, it's going to have an impact on you."

A version of the class is included in training for fire service, emergency dispatch, corrections, and parole and probation. The updated and expanded version now used at the police academy will be duplicated in other academies in the future.

They get another three hours in Stress First Aid, learning how to recognize what causes stress in their work and personal lives and how peer teams can promote healing. It's offered in all the academies but corrections.

"They're going to expect a peer support program" when they're hired by an agency, Maddy said. "That awareness has not traditionally been in the culture."

Recruits also learn how to find and screen a therapist and what to expect in a session.

"Knowledge is power," Maddy said. "The more they are informed, the better off they will be."

She said work is being done by a group of therapists in the Portland area to identify providers across the state who are culturally competent to work with first responders.

A fire battalion chief once told her he went to see a therapist and tried talking about a fatal fire he responded to. The battalion chief wound up needing to take care of the therapist who was shaken by the details he shared.

"As a therapist, that makes my heart hurt," Maddy said. "We need to have people who understand the culture and help them navigate that."

'We don't want people to retire broken'

Marion County Sheriff's Office has what it calls a "well baby checkup program."

The agency works with three public psychologists who Undersheriff Clausen said are among the nation's best when it comes to the psychological impact of trauma.

A peer support team offers outreach for both on- and off-duty crises, which could include a death in the family or a medical issue like cancer. But if a deputy appears to be struggling, he or she may be referred to one of the psychologists.

Visits happen while on duty — the agency will pay for up to five visits — and the conversation is confidential.

All Clausen gets is an invoice that says so-and-so showed up.

"It's all done with the mindset to keep them healthy," Clausen said. "We don't hire broken people, and we don't want people to retire broken."

No mental-health exams are required of Oregon police officers other than routine background checks while seeking certification and employment.

The one exception is when an officer is involved in the use of deadly force, after which he or she is required by Oregon law to complete at least one session with a mental health professional within six months of the incident.

Keizer Police Department takes a different approach, making mental-health checkups mandatory.

Last October it launched the "Healthy Badge" program, contracting with Harden Psychological Associates to provide mental health check-ins with sworn officers and civilian support staff.

The goal, Deputy Chief Jeff Kuhns said, is for all 42 officers and nine support staff to have at least one visit with Dr. Sherry Harden, a noted clinical and police psychologist in Beaverton, before June 30, 2020.

It's a commitment Keizer Police is proud of. It costs the agency $150 for a one-hour session, and 11 employees have participated so far.

The hope is it "will provide police employees with information and support about the common pitfalls of police work and strategies for overcoming them," Kuhns said.

"They will gain insights into how police work has affected them and their relationships," he said. "They will also be able to strengthen methods for alleviating this impact, enhancing stress management and resilience-building strategies, and building or rebuilding healthy relationships."

Douglas, the founder of the National Police Suicide Foundation, believes building and maintaining healthy relationships is critical to suicide prevention among first responders.

"As we teach them how to deal with stressors on the street, we need to teach them how to deal with stressors as they interact with their family and the toxic emotions they experience every single day," said Douglas, who spent 25 years in law enforcement and has been lecturing on the subject since 1987.

He's spoken to audiences the country, including several in Oregon. The most recent was in 2016 at the annual conference of the Oregon Peace Officers Association.

His passion for bringing awareness to suicide and other mental health issues within the ranks, and identifying resources and best practices for prevention and intervention, is as strong today as when he launched the crusade.

"Every time you touch hearts," Douglas said by phone before heading to Wisconsin to address police administrators there. "You might even give them encouragement. You might just get them over the hump where they don't take out their Glock one night and pull the trigger."

Capi Lynn is the Statesman Journal's news columnist. Her column taps into the heart of this community — its people, history, and issues. She was born and raised in the Mid-Valley and has spent her entire career at this newspaper, 30 years and counting. Her brother and sister-in-law both work in law enforcement.

RESOURCES

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline can be reached at 800-273-8255. The Crisis Text Line provides free, 24/7 crisis support by text. Text 741741 to be connected to a trained counselor.

Help is available for community members struggling from a mental health crisis or suicidal thoughts. Suicide is preventable.

The Multnomah County Mental Health Call Center is available 24 hours a day at 503-988-4888.

If you or someone you know needs help with suicidal thoughts or is otherwise in an immediate mental health crisis, please visit Cascadia or call 503-963-2575. Cascadia Behavioral Healthcare has an urgent walk-in clinic, open from 7 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., 7 days a week. Payment is not necessary.

Information about the Portland Police Bureau's Behavioral Health Unit (BHU) and additional resources can be found by visiting http://portlandoregon.gov/police/bhu