PORTLAND, Ore. — Two former interns in the Oregon State Legislature filed a lawsuit on Monday over what they describe as repeated sexual harassment by former state Sen. Jeff Kruse and a failure by legislative leaders to prevent the harassment.

The interns – Annie Montgomery, 31, and Adrianna Martin-Wyatt, 26 – both worked in Kruse’s office in 2017 before he was forced to resign from his position over harassment allegations. The suit names Kruse as a defendant, as well as Senate President Peter Courtney, legislative counsel Dexter Johnson and legislative HR director Lore Christopher.

The two women in the lawsuit accuse Kruse of repeated sexual harassment. They also claim the three other men failed to protect female employees in the Capitol and “for years allowed sexual harassment and took no meaningful remedial action.”

KGW reached out to Kruse, Sen. Courtney, Johnson and Christopher for comment.

Courtney and Christopher both declined to comment stating they could not discuss pending litigation.

Kruse and Dexter have not yet responded.

The lawsuit seeks $6.7 million in damages. The suit was filed in Marion County. Both women said they hope the lawsuit will help create a culture on zero-tolerance for sexual harassment at the state legislature.

“It was blatant,” Montgomery said of the harassment, “It happened in front of other people. People make jokes about it.”

Montgomery told her story to KGW’s Laural Porter just before the lawsuit was filed. Her story was part of a January report from the state Bureau of Labor and Industries, although this is the first time Montgomery has shared her story at length and on-the-record.

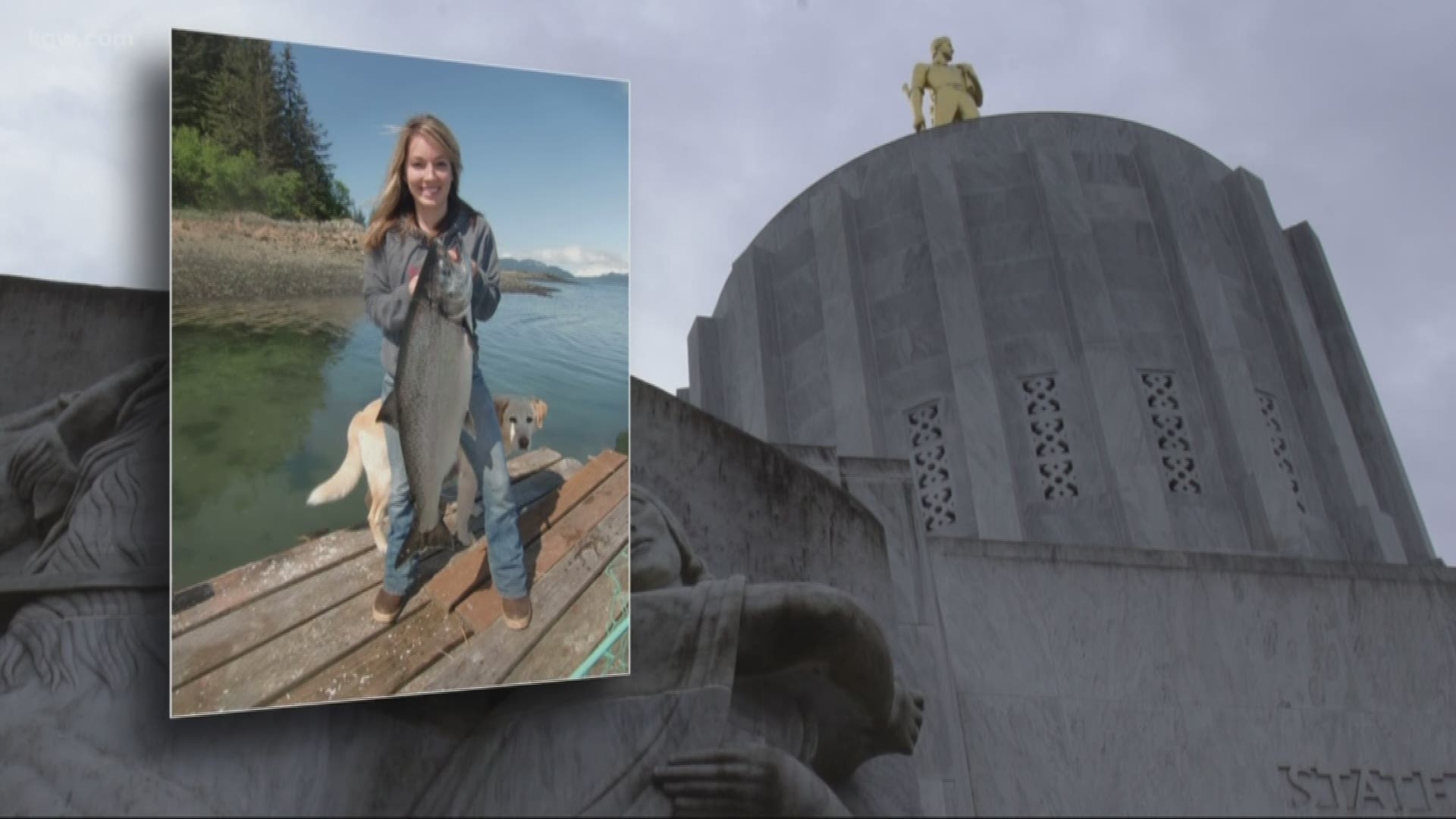

Montgomery describes herself as tough.

She comes from a family of commercial fishermen in Alaska. She went to law school to obtain a degree so she could speak up for the smaller fishermen who she had witnessed being left out of policy decisions.

She’s a licensed fishing boat captain, too.

In the fall of 2016, Montgomery was awarded the Oregon Sea Grant and was placed as a law student intern in Kruse’s office. Kruse, a Republican who represented Roseburg in the state senate, served at the time as Vice Chair of the Coastal Caucus.

“I just remember walking in the building that first day and I had worked so hard to get there, and I had fought against everyone to do it, it was like that moment when you finally realize you’ve made it,” Montgomery said.

She had to withdraw from law school in her last semester to take the position as a paid intern at the Capitol. Despite the naysayers, she felt that this position would help her career.

From day one, Montgomery said she noticed a culture in the legislative offices that tolerated the fact Kruse would inappropriately speak to women and touch them in inappropriate ways.

“The first day it was legislative day and I came in and I met him. Within minutes, I got one of those infamous hugs and I just went, ‘oh.’ It was so uncomfortable to have that first impression to be this long side hug.” said Montgomery.

At orientation, she said other Capitol employees made jokes that during the sexual harassment portion of the day Kruse would take a cigarette break.

Jeff Kruse resigned in March 2018, two years after the first official complaint was filed against him by Senators Sara Gelser and Elizabeth Steiner Hayward for inappropriate touching.

In October 2017, a tweet from Senator Gelser asking “will you ensure no member of your caucus inappropriately touches or gropes female members and staff in cap[itol]” gained media attention. In January 2019 the Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries released a report stating that top lawmakers have not made moves to curb harassment or the hostile work environment at the Capitol.

By the time this report came out, Montgomery and Martin-Wyatt had left their positions as interns.

Montgomery said the violation of her boundaries was frequent. She devised ways to make herself less vulnerable, such as limiting her time standing while Kruse was around. She said he would touch her hips and give unwanted hugs. While sitting, she said Kruse would sometimes reach across to touch her hand, place both his hands on her shoulders while resting his head on hers, or touch her thigh.

She said she took steps to stop the harassment, such as removing his hand from her body or walking away when he would touch her.

When those tactics didn’t work, Montgomery said she drew on a lesson from her upbringing in Alaska.

“We’re taught every time you go on a walk in the woods, ‘what are you going to do if a bear attacks you?’ You’re supposed to play dead,” said Montgomery, “It was this feeling of, ‘I’m in danger, but if I move it’s going to be so much worse,’ so you kind of freeze but you also try not to react.”

Montgomery said Kruse called her “sexy” several times and would refer to her as “my baby lawyer.”

“There’d be a policy discussion about a bill, to include me he would say ‘and what about you little girl, what do you think?’” But no one said anything, and Montgomery felt she couldn’t either.

“Part of sexual harassment is that you don’t ever want them to know that you know, you’re sort of trying to figure out how to get out of this without offending them somehow,” she said.

She focused on trying to do her job.

Montgomery eventually devised a plan with another staffer to move her desk into Senator Betsy Johnson’s office, where she felt protected. She said around powerful women the ‘Mad Men’ atmosphere was less evident.

“I thought maybe, you know I’ve been in law school with a bunch of hippie nerds so maybe I had been in this bubble and I had forgotten what the real world was like at first,” she said. But as she heard more sexual comments in the workplace, Montgomery said she began to realize the Capitol was dominated by a “boys club” attitude.

“You realize, ‘oh, I can’t say anything’. There is no way I am going to complain about this because I would look like I wasn’t a team player,’” Montgomery said.

She had talked about the harassment with other staffers, including her fellow intern, Martin-Wyatt. They both decided to find ways to minimize their time around Kruse.

“We talked about it,” she said, “That was the best we could come up with, just avoid him and don’t be an easy target.”

The lawsuit states that both women suffer from emotional distress, including anxiety and PTSD. Montgomery said she was the victim of domestic abuse in a prior relationship and the harassment by Kruse exacerbated trauma from her previous experiences.

Martin-Wyatt did not sit for an interview for this story but did provide a statement:

“I was not the only woman working at the Oregon State Capitol who experienced inappropriate behavior, and without an intentional change to the culture there, I certainly will not be the last,” said Martin-Wyatt in a statement to KGW. “I often wonder if legislative leaders would be comfortable with their daughters or granddaughters working at the Oregon Capitol. What actions would they have taken if someone they cared for were about to start working in Senator Kruse’s office?

The leaders knew what Kruse did to women long before we ever worked for him and I believe that they would have made sure their loved ones did not work for Kruse. But protecting all persons in that Capitol, not just those they care about, is part of each of their job descriptions - jobs they asked for and agreed to do.

We must have zero tolerance for sexual harassment, even if the perpetrator is somebody we like and admire, or is a political ally.

Unwanted touching, innuendo, and propositions from people in positions of power have no place in our democracy.”

Montgomery said she has only recently found the courage to speak publicly about her experience in the legislature. She testified at a legislative committee hearing in early February and said she couldn’t sign her name in for fear of putting her name on paper because of negative career implications.

“But that has already happened to me, I couldn’t get a job answering phones in that building and I just kind of wanted to confront everyone and say, ‘Listen I know what this is like on the other side,’ talking about women and how they report and what happens.”

Montgomery wanted to be a policymaker, not spearheading a movement against sexual harassment in politics.

“This is my nightmare,” she said of the news coverage. “I never wanted to be known for this. I didn’t want to be a victim, especially again, and so it’s hard to get to that point.

“The only thing that has made me able to identify myself at all is that it doesn’t seem like there is a lot of movement toward making it better and wanting to protect other women,” she added.

Montgomery feels as though she has already been blacklisted in Salem.

“Now I am seen as difficult or unwilling to be a team player, a lot of the political jockeying is about trust and it’s about trusting the person in your office isn’t going to talk and I talked, and I think that I am sort of in the position of whistleblower.”

But she will stay involved until movement is made.

“I think that a strong policy about retaliation would be the first step,” she said. “We shouldn’t be terrified that our names are going to come out because we said that something that happened to us was wrong and made us terrified and not want to go to work.”

She feels that the state Bureau of Labor and Industries should be trusted to handle investigations of this nature in the future and not someone employed from within who could be put in a bad position by reporting.

Her suggestion for women in a similar position to hers is simple: write things down because believability will be questioned.

“Write it down, tell someone about it, tell them to write it down, keep track of everything you can, time of day that it happened and especially write down how it made you feel,” stressed Montgomery, “I think that it can get lost in the – having to explain what happened is so awful that explaining how you felt when it was happening can end up lost in the shuffle. When you write down everything really focus on how it made you feel.”