'She can still learn': School for homeless children delivers class work, food to students during pandemic

Community Transitional School, a Portland nonprofit that serves homeless children, provides more than just education to its students.

On a rainy Monday morning, the hallways of a gray, one-story school in Northeast Portland are empty and quiet, just as they will be throughout the day. Months into a global pandemic, with COVID cases and hospitalizations surging, there's nothing unusual about that. Most Oregon schools are relying solely on remote learning.

What makes operations at the Community Transitional School unique is the fact that the bus drivers are busier than ever.

"Our kids don't have a lot of access to the internet," says principal Cheryl Bickle, who also teaches third through fifth grade. "So we started doing delivery."

The Community Transitional School is a decades-old nonprofit that serves children experiencing homelessness. Before the pandemic, bus drivers picked kids up and dropped them off wherever they lived: shelters, motels, camps, vehicles parked on Portland's streets, etc.

By mid-November, Bickle says, they had their remote-learning routine ironed out.

"We decided that we were going to deliver breakfast and morning work," she says, referring to the brown paper sacks, stuffed with food, sitting alongside plastic bins containing class work and reading assignments. "We pick it up at lunchtime when we deliver lunch [and afternoon work] and then start the whole routine again. And that has worked really well."

Teachers grade the morning work in the afternoon and the afternoon work the next morning, she adds. Roughly three-quarters of the school’s 76 students in grades kindergarten through eighth grade turn in at least one assignment every day.

Still, staff worry. In normal times, housing insecurity breeds chaos and anxiety for kids. The school has always provided a stable haven, with administrators even allowing students to remain on board after their families find housing because it’s familiar.

Now, that haven, like schools across the state, is closed.

"One of the purposes of our school is to make the children believe in themselves and their ability to succeed," Bickle says. "It's really hard to do that when you don't see the kids."

'Is there anything you don't understand?'

The morning route starts around 8:30 a.m., with three buses making a total of 76 stops. Each bus has a driver and a staff member or volunteer on board.

On Monday morning, Bickle rides with Aldin Porcic, the school's transportation coordinator and facility manager.

They stop at two motels and a shelter before pulling up to a third motel near Southeast 92nd Avenue and Foster Road.

The McDowell brothers are waiting by their front door.

"Hi Xander!" Bickle calls as she steps off the bus, holding folders and brown paper bags containing milk, apple sauce and other breakfast items.

The 10-year-old boy, wearing a black hoodie and a mask with monsters on it, hands Bickle his schoolwork from the day before in exchange for his new morning assignments.

Xander is good at math, Bickle explains.

"Is there anything you don’t understand about your work?" she asks.

"No," Xander says, holding his breakfast.

"I’ve been really proud of the way you’ve done it," Bickle says. "I'm really proud of the way your penmanship is changing."

Then, turning to 6-year-old Kyngston, she adds, "And I hear good things about you."

The boys' mother, Amber Ellenberger, stands between her sons, holding their newly assigned class work. It's work for her, too.

"I work the nightshift [as a caretaker], and then I come home and I have to do the homework and all that," Ellenberger says. "It's been a very difficult challenge. Plus, with having a third grader, I'm re-teaching myself some of the math also, which is very difficult because I'm not a teacher."

County officials placed the family of five in their motel room in August. They'd been on the waitlist for a year, she says. For months before that, they lived in their car. She didn't dwell on the difficulties of it.

"I guess I just live it, and I don't think about it," Ellenberger says. "I just do what needs done, and that's what it takes."

While he misses in-person learning, Xander says he likes seeing the bus pull up every morning and afternoon.

"It makes me feel good because I used to go to school, and it made me feel good," he says.

His younger brother is more focused on what this new routine lacks.

"There’s no playground," Kyngston says.

Bickle boards the bus and waves as it pulls away, promising to be back in a few hours.

Sidewalk teaching

After the morning route wraps up, Bickle's bus returns to the school. Teachers divvy up the work collected from their students and prepare the afternoon assignments to be delivered next.

Porcic brings out a stack of folders, ready to be loaded back onto the buses before they depart again at 12:30 p.m.

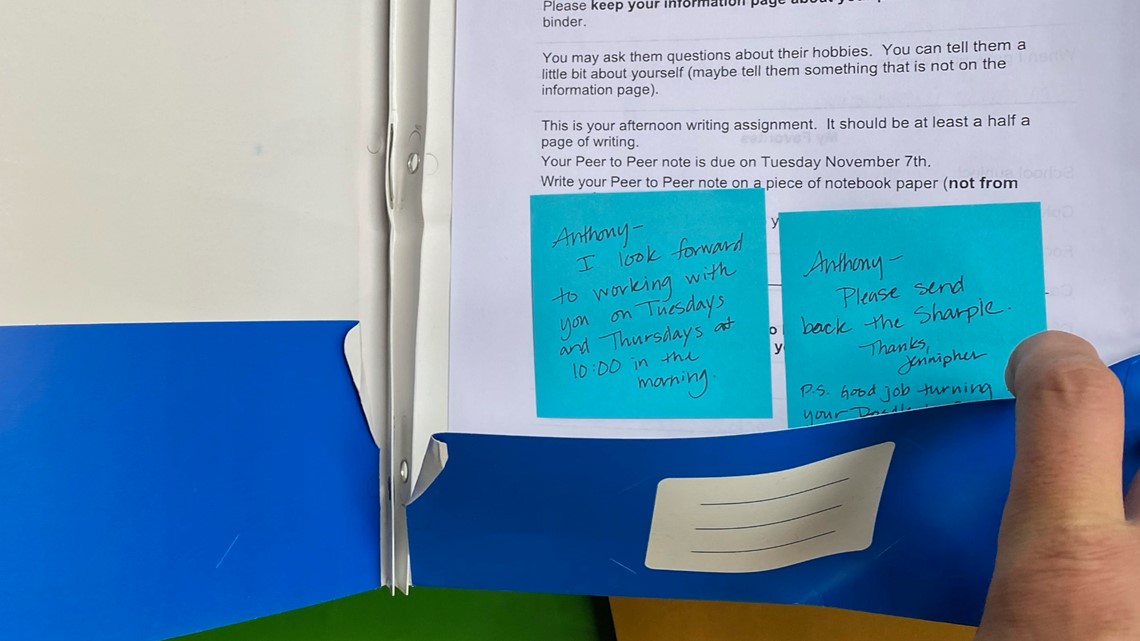

The stack includes instructions on art projects and journals, which kids are encouraged to keep during the pandemic. Others have Post-it notes attached with instructions from teachers.

"Anthony, I look forward to working with you on Tuesdays and Thursdays at 10:00 in the morning," one reads.

It's a tactic that teachers relied on heavily early in the pandemic, Bickle says. They called it "sidewalk teaching."

"We would just stand outside in the parking lot and go over some of the work that they were having a hard time with," she says. "And then when the [COVID] numbers started to surge, we thought maybe we need to give this up right now."

In the months since, she notes, staff and students learned more about the virus. Masks are now a requirement, and while they’re not common, one-on-one sessions are permitted if they're outdoors.

The hardest part comes when kids call with questions about their work, then make it clear they just want to talk.

"[They want to talk] about just their family, their older brothers are bothering them or, 'When is this going to stop?' And 'It's really no fun,'" she says. "Like I had one girl say in her journal this summer, 'This will be remembered as the summer of no fun.' And I thought, 'Well, that's probably true.'"

'She can still learn'

The afternoon route, complete with bagged lunch and the second round of class work, begins at 12:30 p.m.

Bickle's bus pulls into a motel along Northeast Sandy Boulevard near Northeast 122nd Avenue. She steps off and knocks on a door.

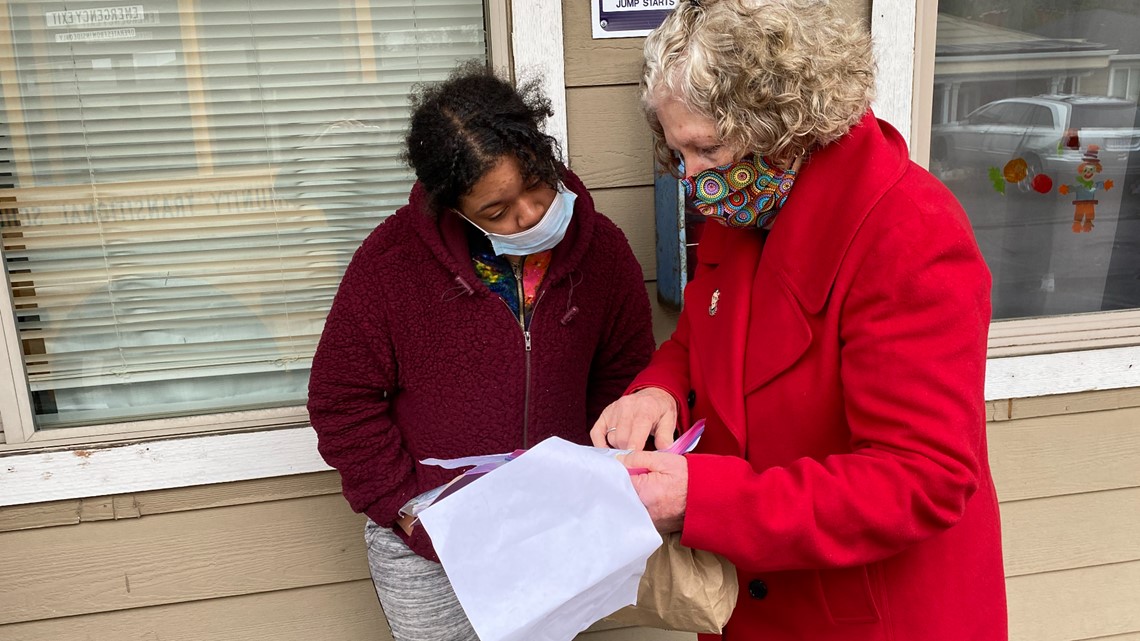

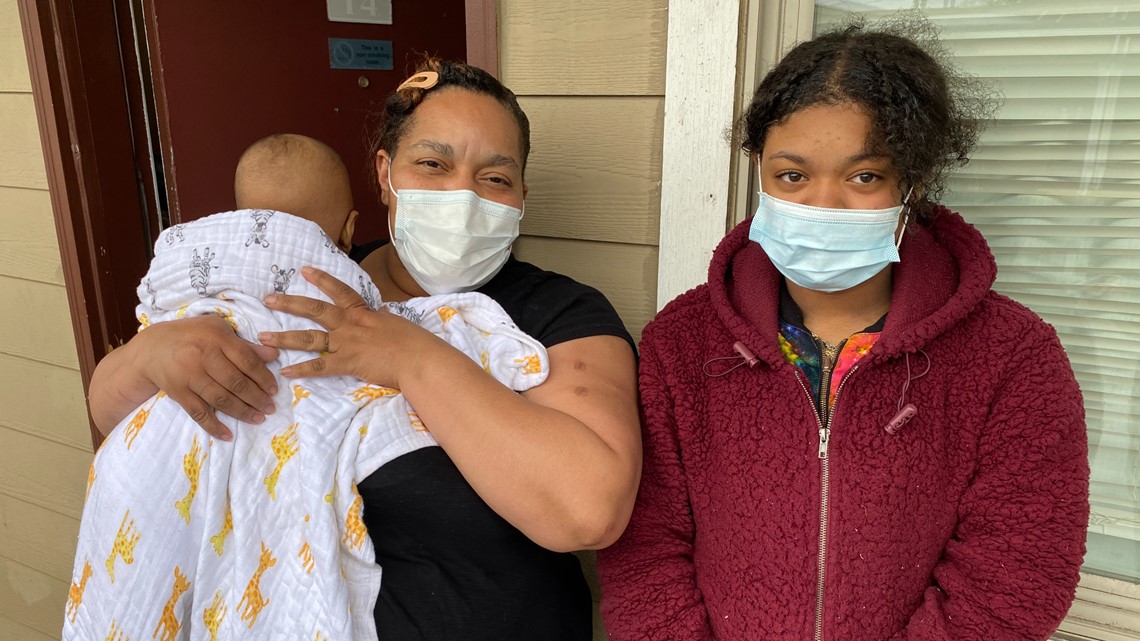

Sheri Brown answers with her infant son in her arms and her 10-year-old daughter by her side. Areeshia Holloway is another student of Bickle’s. She comes out into the parking lot to talk about a math assignment Bickle had brought back, graded.

"Right, so you’ve got to do this," Bickle says. "Let's figure this one out."

Areeshia reads a problem from the assignment out loud.

"He had 600 buttons, but 62 are left," she says. "How many has he used?"

As Bickle walks her through the word problem, Brown comes farther outside, wrapping her baby Genesis in a blanket.

"He’ll be five months tomorrow," she says.

The family has been together in the motel room for a month. Before that Areeshia was living with relatives while Brown completed in-patient rehab, she says.

"I was kind of going through some depression and some other things," she says. "But we're here now, and hopefully we won't be here too much longer. It's kind of small, but it's OK. It's a place to stay."

At 43 years old, Brown is a mother of five children. Her three oldest kids, now in their teens and twenties, all went to the Community Transitional School, she says. The resource has never been more valuable than during the pandemic. Not only do staff bring schoolwork and meals twice a day, five days a week, they also bring boxes of food every Friday to last families through the weekend.

"I thank God for CTS," Brown says. "I know it's hard on [the staff], but they do it anyways. They make it to where she can still learn and other kids can still learn as well."

After a lesson that lasts less than five minutes, Areeshia solves the word problem.

"You did those right!" Bickle says.

Handing off the afternoon work and bagged lunch, she turns toward the bus and promises someone will be back tomorrow, twice.