PORTLAND, Ore. — Educators across the country have said for months that this school year has been especially tough, and coming back to school full time after so much distance learning was hard on students and teachers.

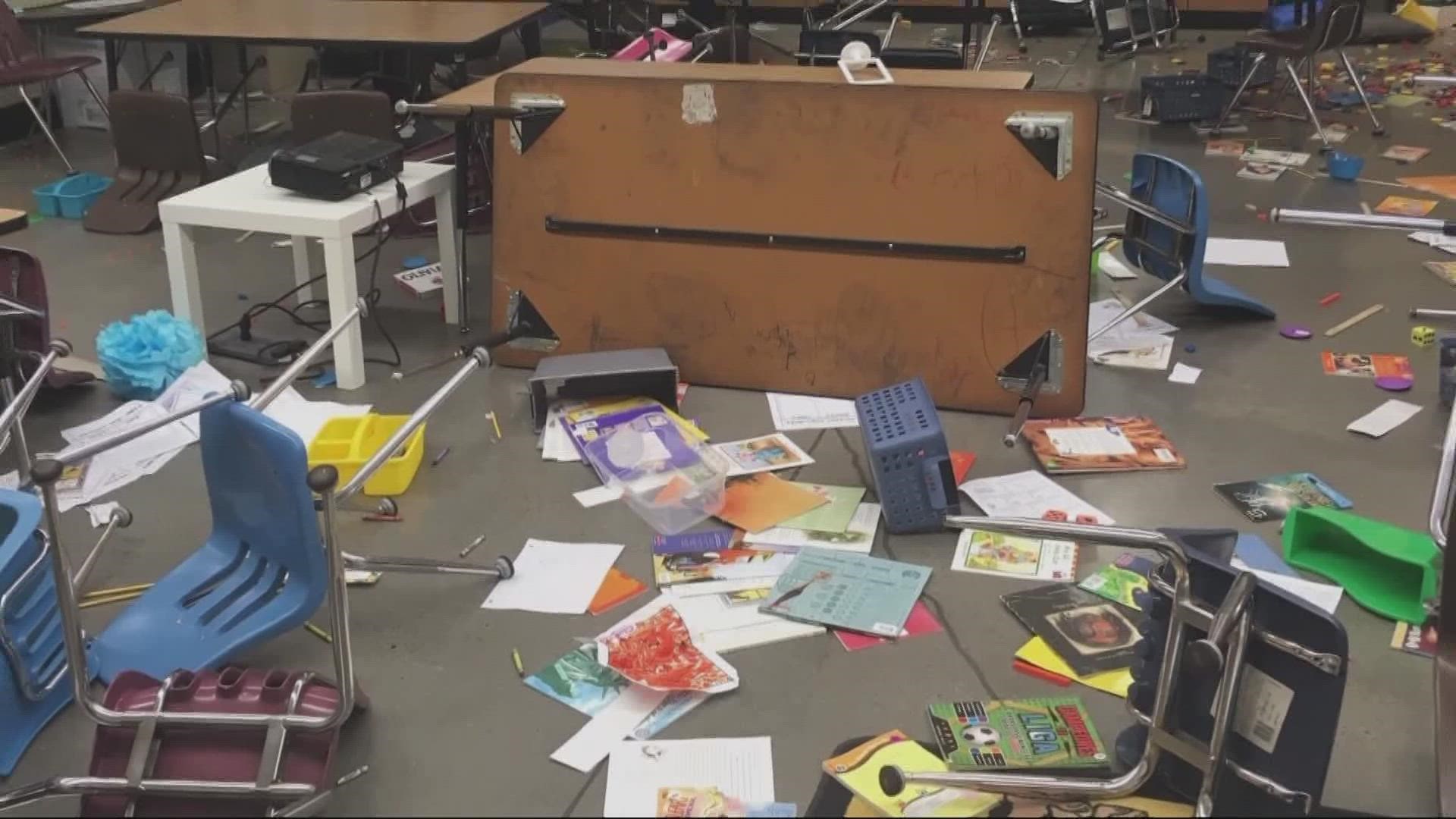

Those struggles have, in some cases, manifested as violence in and outside the classroom.

Colin Hawkins is a science teacher at Roseway Heights Middle School in the Portland Public School District (PPS). He and his colleagues have seen a lot this year. The first few months of the school year included a large brawl and school walkout.

Other educators within PPS told KGW that student behavior and outbursts are issues they deal with on a near-daily basis.

“The behaviors we're seeing are violent to a level that I haven't seen in years past,” said Hawkins. “Teachers have been hurt. Kids have been hurt. I've seen kids savagely beaten in the hallway... Kids will go and solve things at a park nearby.”

He said most recently, there has been a growing sense of vigilantism among students.

“Students are trying to police behaviors on their own, which is not good,” Hawkins said.

Hawkins described a recent incident where students entered a classroom because they were trying to defend a friend that was being bullied.

Outbursts and violence in the classroom had already been trending up before the pandemic, as KGW revealed in the Classrooms in Crisis series during the 2018-2019 school year. But many educators have said the pandemic made things worse.

RELATED: Evergreen Public Schools to cut nearly 200 positions, including some designed to improve equity

Inside special education classrooms

"I know at our school we've had more physical altercations, more staff injuries due to student behaviors than we ever have had and more disrupted learning due to behavioral outbursts," said Mary Darin, a speech language pathologist.

She said she and her colleague, Nathan Earle, who is a licensed clinical social worker, have both been injured to an extent that required medical attention this year. Darin said those types of situations are becoming more and more common.

Both Darin and Earle work with special education students.

“We're seeing hitting, kicking, spitting a lot more this year than ever before,” said Earle.

He said staff have innumerable scratches, bites, bruises and bleeding on extremities. In some cases, educators have received concussions or a broken nose.

“It's become very serious and it's on a daily basis that a staff member will near-daily come away with some kind of physical manifestation of their day at work,” he said.

Darin said the most difficult part is a lot of times, educators know what their students need to thrive, but there isn't enough staffing to support students in the ways they need.

A 'crisis' at the middle school level

Elizabeth Thiel and Angela Bonilla, the president and president-elect of the Portland Association of Teachers said whether general education or special education, much of the violence is happening at middle schools. Sometimes staff are injured while trying to break up a fight between students and other times they're injured due to direct aggression from a student.

“This year has really felt like a crisis at many of our middle schools,” said Thiel.

She said it's been difficult on some kids, who are now 7th grade students, but the last time they were in school was when they were in 5th grade at the elementary level.

“It's not all middle schools equally that we're hearing from. Schools that serve students who are most likely to be taking on the brunt of the impact of the pandemic are the same schools having the most challenge dealing with student behavior,” she said.

Educators said not only are they seeing more behaviors, but those outbursts are also more extreme. They said many students have a lower frustration tolerance.

Districtwide data on fights and disruptions

As of Feb. 28, data from PPS showed fewer incidents this year than previous years.

In the 2021-2022 school year, there have been 1,625 reported incidents of fights and physical aggression. The same period in the 2019-2020 school year saw 2,613 incidents, while for the 2018-2019 school year the number was 2,334. (Data for 2020-2021 was not included because nearly the entire year was spent distance learning.)

For disruptive conduct, this year 1,097 incidents have been logged, but similarly, numbers were higher in previous years.

Thiel and Bonilla weighed in on possible reasons for the discrepancy.

“That is something we frequently hear from educators. How many times do I document the same thing and get no response before I stop using my time that way?” said Thiel.

“It's exhausting to use our planning time that we have so little of to have to document behaviors and student incidents that don't get followed up on,” Bonilla said.

They also said in previous years there have been backlogs when processing documentation. Other educators like Darin and Earle said it’s possible two different reporting systems for special education students may also play a role in the discrepancy.

But one thing is clear: they all say students are experiencing more need than ever.

"Over 225 suicide screenings in quarter one, compared to 91 in quarter one of 2019," said Bonilla.

A response from the district

Administrators at the district level said they know the need is high.

"More data is showing that there are less referrals this year, but our students are demonstrating more overt behaviors, such as running out of the classroom in elementary, fighting or substance use issues in our secondary," said Brenda Martinek, chief of student support services for Portland Public Schools.

Martinek said the district is trying to help classrooms that need the most support.

"We do have additional staff that are out there, working in our classrooms, helping specific teachers, helping to identify and then support the behaviors with some plans," she said.

Martinek also said the nationwide staff shortage doesn’t help efforts to fill positions in special education classrooms and elsewhere.

"We're trying to get some more support out there," she said.

Martinek said money from the state allowed the district to put more counselors, social workers and other mental health providers in schools.

"We also decreased our overall class size in some schools," said Martinek.

She said a new commitment to a policy around discipline is more supportive and less punitive in nature.

"In restorative justice we do have circles and we talk about the harm that's been caused and each person gets a chance to open up and really talk about that," Martinek said.

Educators say they need more support and resources to meet student need

But teachers like Hawkins aren’t convinced the discipline system is working.

"What they'll tell the community is we're doing things like restorative justice, we're doing things like having a study hall room where they're gonna be working with your kids," Hawkins said. But he said at his school, the room meant for students to talk about and work through issues isn’t staffed.

"That position has been open all year. So we have no room for that," said Hawkins.

"We have one person who's running, I believe they have six schools that they're supposed to do a restorative justice program in. They don't work in our school, they work at the central office," he said.

What Hawkins and other educators say it comes down to is more adults or fewer kids per classroom to make sure kids’ needs are met.

In early May, the Portland Association of Teachers said data from the district indicated there would be 26 fewer licensed special education staff in classrooms next year if the proposed budget is approved.

That had special educators in particular reeling. On Monday, a Portland Public spokesperson said that number is now down to five fewer full-time special education staff.

However, educators said students need more support, not less, especially right now.

"We want each of them to be treated as individuals and provide them with what they need to access a great education. We're not going to be able to do that, given less of us. We are already really struggling to meet their needs," said Earle.

"With you know 30 kids in a classroom, all with highly disparate need levels, the decisions become more of triage and less of like a positive educational plan," Hawkins said.

He said often, teachers are faced with a near-impossible choice: to focus on the student who is having an outburst or struggling the most, or teach the majority of students in the class.

"That's a decision that we have to make on a daily basis and it means that somebody is left out, either the majority of students are left out or a minority of students are left out," said Hawkins.

Additionally, he said there aren't enough staff to be present at recess, lunch, or during hallway time. There are also no cameras in school, which makes it difficult to corroborate students' stories about what may have happened in a school hallway.

'We see them. We hear them.'

Martinek said the district is trying to help and appreciates everything educators are doing.

"What I want them to know is that we see them. We hear them. We are trying our hardest to try and provide those supports to them. I don't want to give excuses about the staff shortage, but it is real. And I applaud them for their work. It's just a really, really tough time right now," said Martinek.

The school board is scheduled to vote on approving the budget at its board meeting Tuesday. May 24. A second and final approval vote is expected in June. Between now and then, the budget could continue to change — a Portland Public Schools spokesperson said just last week, the district discovered $9 million in surplus that will go toward supporting students with more staff and counselors. The details are currently being worked out.