PORTLAND, Ore. — For several schools in the Portland area, remote learning is making a comeback. The main reason is that too many teachers are calling out sick because of the quickly spreading omicron variant and there's a shortage of substitutes to take their spots.

So far, a handful of schools in the Portland Public School district have been moved to remote learning. The entire Parkrose School District is doing the same and the Vancouver School District has followed suit.

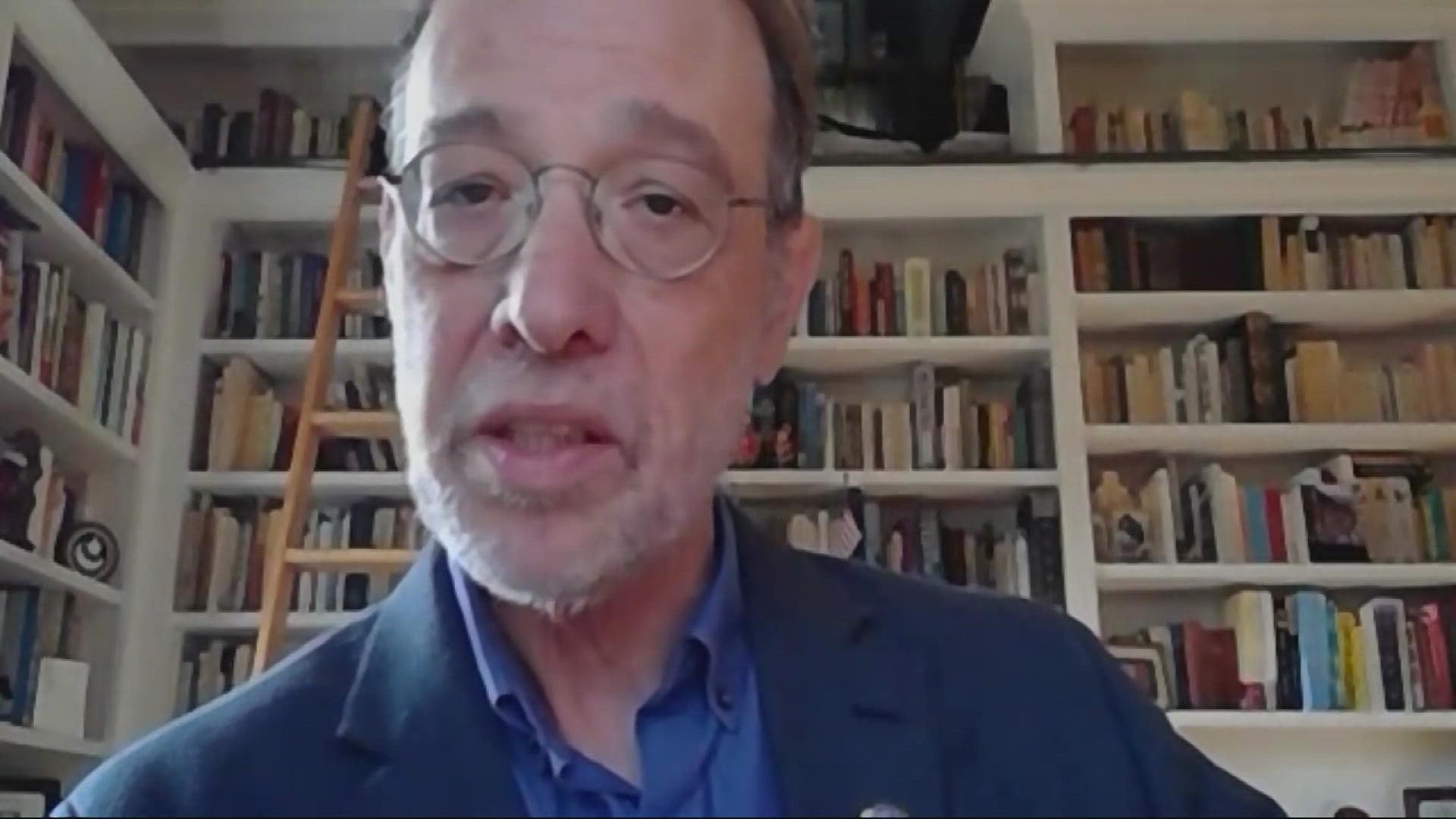

Staffing issues are plaguing school districts all over the country as well. In Oregon, Senator Michael Dembrow is hoping to help fix the school staffing crisis.

“The problem is getting worse by the week with omicron,” said Dembrow.

He represents a swath of northeast and southeast Portland and chairs the Senate's education committee. In December, he put together a workgroup of about 50 people, including legislators, teachers, parents and other people with ties to education.

RELATED: Portland, Vancouver schools transition to distance learning due to COVID staffing shortages

“The goal here, immediately, is to come up with some short-term solutions that we can address in the upcoming short session, the legislature, which starts in February,” Dembrow said.

The workgroup was separated into subgroups tasked with examining a variety of issues, from licensing and recruitment to teacher burnout. Dembrow said a couple of critical problems stood out.

“I hate to say it but our substitute teacher system is really dysfunctional,” said Dembrow.

“The other problem area is in special education. That is really difficult, challenging work,” he said

“The most crucial members of that workforce are the assistants who are pretty poorly paid. They can definitely be earning, in today's job market, much more in other occupations that are much easier, frankly, to do.”

Most of the proposed solutions involved the state putting more money toward the issues, which would need legislative action, to pay for things like incentives, increased pay, or even loan forgiveness.

“Helping with licensing fees to get people back into the profession right away, to help substitutes, to help, you know, attract substitutes […] those kinds of things,” said Dembrow.

Dembrow said he believes barriers to licensure for people who are moving to Oregon from other states, should be streamlined. In addition, he said parents, volunteers and community-based organizations are likely part of the solution and the possibility needs to be examined.

When asked about a timeline for the short-term solutions, Dembrow said he was not sure when dollars might be distributed to districts, but there were non-financial solutions he thought could immediately be put into effect.

For instance, teachers have said they need more time to spend with individual students this year because there is so much more need mentally, emotionally and academically. In addition, some teachers have to file regular reports and fill out other paperwork that takes up their time. Dembrow said if the state can take away some of those requirements for this year, that would give those teachers more time with students and more time with each other to plan and prepare.

He said if the state gets to the school staffing issue in February during the legislative session, it's likely any money given to schools would be federal dollars or surplus the state has saved up.

“The first thing that we need to do […] we need to get a better sense of just how individual districts are already spending the dollars that they've received, the federal dollars,” Dembrow said.

RELATED: Oregon reports 18,538 COVID cases over the weekend

He was referring to federal COVID relief money that he said can be used to recruit and retain educators.

But even while solutions are labeled "short term,” Dembrow said they still take time. If a bill with proposed solutions is passed in the short session, he said it's possible additional money could go out to districts in late spring or summer.

“That will help districts in their planning for next year.”

But if the staffing issue isn't addressed in the legislative session, he said financial help may not come until the 2023-2024 school year.

“So it really is important that we see what we can do right away,” said Dembrow.

Later this week legislators will meet to prioritize the proposals. Eventually, those proposals will be written into a bill and then the short session will start in February and last for five weeks. Dembrow said it's possible the bill won't go anywhere because the session is so short and there are other bills and issues that need to be discussed, but Dembrow hopes that's not the case.

Down the road, he said the group will also look at long-term solutions to the staffing shortage.