PORTLAND, Ore. — Opening arguments began Thursday in a civil trial arising from the 2021 deadly shooting of a Portland man by a private security guard outside of Lowe's Home Improvement in Delta Park. Last year, a Multnomah County jury convicted security guard Logan Gimbel of second-degree murder, earning him a life sentence in prison.

Gimbel shot and killed Freddy Nelson Jr. as he was sitting in his pickup truck next to his wife, Kari Nelson, in the Lowe's parking lot on May 29, 2021. Court documents claim that there was an ongoing personal dispute between Freddy Nelson, the property managers and Cornerstone Security Group, the firm that employed Gimbel.

A few months after the shooting, Kari Nelson filed a $25 million negligence and wrongful death lawsuit, naming property managers TMT Development Co., property owners Hayden Meadows, three representatives of Cornerstone Security, and Gimbel.

READ MORE: Family of man shot, killed in Lowe's parking lot by armed security guard suing for $25 million

The complaint alleges that the property owners failed to do their due diligence on Cornerstone and that Cornerstone was fundamentally a fly-by-night outfit that purported to provide armed security professionals.

"Several Cornerstone individuals, including the security guard that shot and killed Freddy Nelson, Jr., were not certified to carry any firearms, much less open fire on an unarmed man," the complaint says. "The uncertified individuals that the Cornerstone Defendants employed as armed security professionals disregarded the law and illegally carried firearms.

"The Cornerstone Defendants fostered a work environment that glorified violence, ignored de-escalation training, and instilled disregard for human life."

Cornerstone hired Gimbel in August 2020, the complaint alleges, despite him lacking certification to work as armed security, a potential violation of Oregon law.

Plaintiffs: Kari and Kiono Nelson

Jury selection in the trial wrapped Thursday, and the court quickly transitioned to opening arguments. First up was Tom D'Amore, the attorney for Nelson's family.

At the time of the shooting, Delta Park Center was owned by Hayden Meadows. They employed TMT Development Co. to manage the property, and leased portions of it out to different businesses, including Lowe's. TMT hired Cornerstone to provide armed security on the property.

D'Amore described how Nelson had an agreement with a manager at Lowe's to pick up broken pallets from the business, and he'd make money by selling them for recycling. But D'Amore said that TMT Development had a "zero tolerance policy" for rule-breaking, per a Cornerstone memo, and that led to security guards harassing and intimidating Nelson whenever he came onto the property.

Other internal Cornerstone memos would show that their policies were for guards to smile, be polite, but "have a plan to kill everyone you meet," and D'Amore said that the evidence would show that their guards were prone to escalation rather than de-escalation.

Another internal memo, D'Amore said, talked about a "rash of unnecessary deployment of long guns during incidents in the field."

Despite that, D'Amore suggested that even Cornerstone had concerns about the zero tolerance directive from TMT, citing both state regulations and potential liability, leading to an overall lack of clarity on what was expected of them.

"TMT believed that they could exclude anybody from going into, for instance, a Lowe's," D'Amore said. "They believed they could shut down a store by not allowing anybody in."

D'Amore previewed bodycam video from Cornerstone's guards, showing several of their encounters with Nelson outside of Lowe's. In one, Nelson has pallets stacked on a trailer behind his pickup when the guards approach, with one guard audibly telling a colleague that he'd "rather do a show of force on this guy."

For his part, Nelson largely ignores the guards when they tell him that he's excluded for the property for a year, saying, "Whatever." He also references Brian Hugg, the name of a TMT maintenance manager who, D'Amore suggested, may been putting pressure on Cornerstone to keep Nelson off the property.

D'Amore then played the bodycam video from Gimbel on the day of the shooting in the Lowe's parking lot. The attorney described how Gimbel partially blocked in Nelson's pickup, then approached the vehicle with both Nelson and his wife inside. After yelling at them to leave, saying they were trespassing, he took out pepper spray and fired it into the truck.

Nelson had his own can of pepper spray and rolled down his window to retaliate, D'Amore said, when Gimbel sprayed again, hitting Nelson "directly in the face." D'Amore said Gimbel then moved around to the front of the truck as he and Kari Nelson shouted at one another.

"I'm calling the police," Kari Nelson said as she got out of the truck, just as her husband started the ignition.

Freddy Nelson started to drive, lurching forward slightly before pausing, throwing it into reverse and beginning to move back. Gimbel, now yelling at Nelson to get out of the pickup, saying that he'd "already tried to hit (Gimbel) once," then shot four times through the windshield, hitting and killing Nelson.

Kari Nelson can be heard screaming incoherently after the series of shots.

"I told you to stop and do not angle the vehicle at me!" Gimbel shouted. "Call the authorities, now! I told you not to move the vehicle, I told you!"

READ MORE: Private security guard in custody after grand jury indicts him for Lowe's parking lot shooting

After showing the video, D'Amore said that the defense would likely point to Freddy Nelson's flaws, including past domestic violence incidents with his wife and his use of methamphetamine. Nelson had meth in his system on the day he died, D'Amore admitted. But, the attorney indicated, Nelson was not the type to escalate his encounters with security.

"You saw his manner in three videotapes," D'Amore told the jury. "You have a pretty good impression in these videotapes ... of his general reaction to very stressful situations where people were harassing, humiliating and threatening violence against him. He knew better than to, when these guards with their guns or whatever came up to him, his basic response was 'whatever' a few times, and would get in his vehicle or would walk away."

Nelson and his wife were married for 30 years, and were living together in a converted bus. At the time of his death, Nelson was estranged from his three children.

The defense would try to paint Nelson as a transient, D'Amore said. Despite claims that Nelson was complicit in criminal activity, TMT and Cornerstone never pursued a civil or criminal trespass against him, and D'Amore argued that there wouldn't be evidence to support accusations of criminal conduct.

"He wasn't a disruption; he wasn't causing harm. That's what you're going to see in the evidence of this case," D'Amore said.

Defense: TMT Development Co.

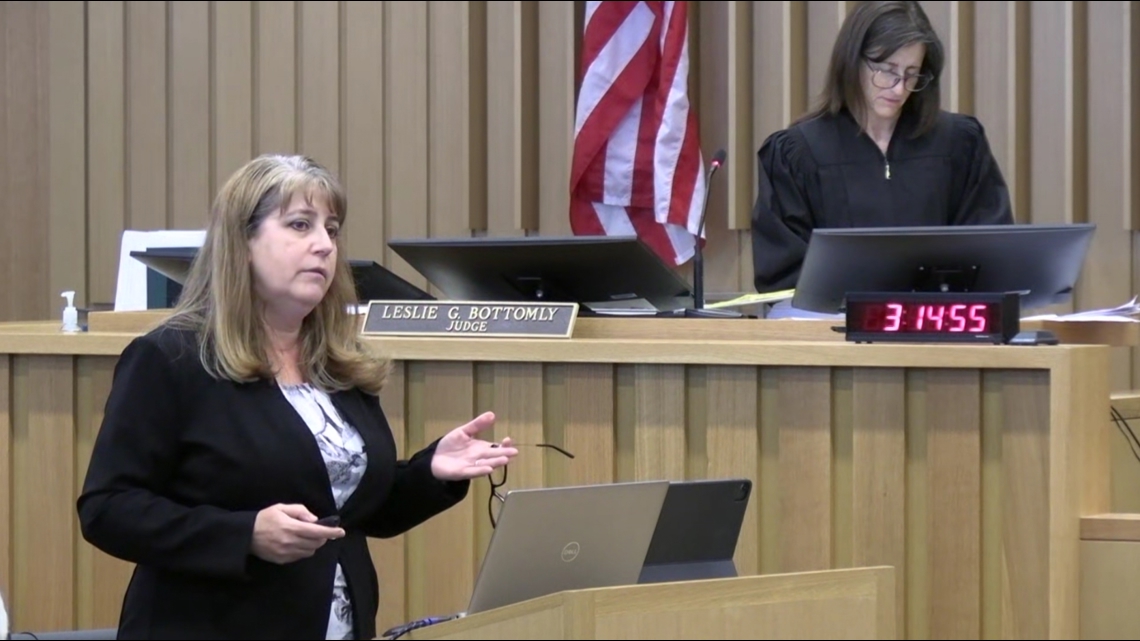

Unlike the plaintiffs, the defense in this trial was split into multiple — and at times, competing — interests. First up for the defense was Sharon Collier, the attorney for property management firm TMT Development Co.

Collier acknowledged that the shooting was "absolutely horrific" and expressed sorrow for the loss to Nelson's family. But, she argued, the blame on her client has been misplaced. It wasn't negligence from TMT that caused Nelson's death, but an intentional act by Gimbel, nothing that the property managers "endorsed, encouraged or foresaw."

In addition to Gimbel, Collier's client places the blame on Cornerstone, which "they were led to believe" could provide experienced and highly trained private security.

TMT did not hire Cornerstone for loss prevention, which the individual businesses might do themselves. Instead, Collier explained, Oregon law requires that property owners in high-crime neighborhoods take "reasonable steps" to prevent, deter and protect tenants from the risk of harm.

When TMT hired Cornerstone, Collier said, the security firm had no prior complaints against its license or business, and it came highly recommended by some of the tenants at Delta Park Center, the name for the property where Lowe's sits.

"This is a very challenging property," Collier said, calling it a known hotspot for sex trafficking, gang activity, violent crimes, drug dealing and use, shoplifting and homeless camps set up on nearby Oregon Department of Transportation property.

Before Cornerstone, TMT employed an unarmed security firm that was "not doing a sufficient job of protecting and maintaining the security" at Delta Park Center. They didn't price shop because they wanted the best firm out there, Collier said — and specifically an armed one, something that TMT still believes is necessary.

Collier said that as of November 2019, the estimated cost of security for Delta Park Center was expected to double by hiring Cornerstone, up to $155,168 per year. After the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020 and TMT decided to expand the security presence there, they paid over $423,430 for the year.

Part of the reason for that, Collier said, was because the BottleDrop location on the property had been "flooded" with patrons as other bottle return locations in the Portland metro area shut down. In late March 2020, Lowe's complained about the long lines obstructing their shared parking lot.

TMT had Cornerstone bring on more guards to manage the BottleDrop lines, charging the Oregon Beverage Recycling Cooperative (OBRC) for the extra expense and causing a dispute between BottleDrop and TMT that dragged on for some time.

Of particular note, Collier said, was that BottleDrop lodged several complaints about the behavior of Cornerstone guards. TMT investigated the complaints and had lawyers look into them, but Collier said that they weren't substantiated.

As for the "zero tolerance policy," Collier told the jury that this was never an official policy of TMT but rather the theme of a meeting that maintenance manager Brian Hugg and the associate property manager had with Cornerstone. In July of 2020, they told Cornerstone that they felt guards were allowing certain violations to occur on the property, and they had "zero tolerance" for those violations. But they didn't direct the security firm to break the law, Collier said.

There were no memos directly attached to that meeting, but a Cornerstone rep later penned one from memory which included some "some self-serving statements," Collier said, and Hugg's testimony would not endorse it as TMT policy.

Collier said that Hugg, the TMT maintenance manager, had met Nelson many months prior to the shooting, when he found Nelson's bus parked along Kerby Avenue near the Delta Park Center businesses. While a public street, Hugg eventually tried to get Nelson to relocate, Collier said. They had a few interactions, and Nelson's bus remained there for 15 months, Collier said.

In April 2021, TMT's property manager received a report from Cornerstone about Nelson, Collier said, alleging he'd "harassed, threatened and undermined" their security guards for over a year. While they'd trespassed him from the property, they said, a manager at Lowe's continued to let him come pick up pallets.

Whatever the local manager allowed, Collier argued, Lowe's corporate policy is to allow only "approved vendors" on the property for things like pallet disposal, and TMT's own policies require that vendors be licensed, bonded and insured. After getting the report from Cornerstone, TMT's property manager contacted Lowe's corporate — ultimately getting the answer from an executive in North Carolina, Collier said, that Nelson was not an approved vendor and should be trespassed from the property.

TMT's property manager asked the Lowe's corporate rep to communicate this to the local manager, then went to Nelson himself. According to Collier, the property manager told Nelson that he wasn't authorized to be on the property.

After talking with Cornerstone, Collier said the security firm claimed that they first trespassed Nelson after May 2020 when they once found him engaged in a "fistfight" and, one another occasion, he was allegedly seen helping a shoplifter get away. They also trespassed him for picking up pallets due to the Lowe's corporate and TMT policy, Collier said.

Regardless, Collier said, the behavior of Cornerstone's security guards toward Nelson was not justified, and TMT's property manager had told them to "not to engage with Nelson."

"If Cornerstone had done what the property manager requested, this wouldn't have happened," she said.

She suggested that the claims of Nelson's family would more accurately amount to $4 million for wrongful death and $2 million for emotional distress.

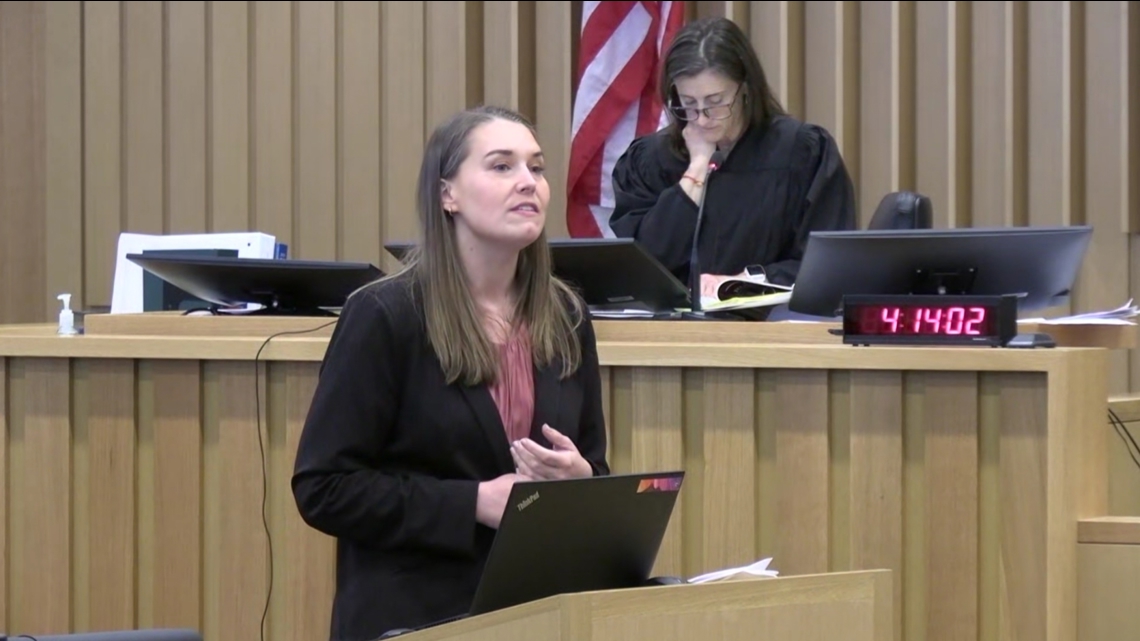

Defense: Cornerstone Security Group

Finally, the attorney for Cornerstone's three representatives, CJ Martin, delivered her opening arguments. She said that the company admitted to negligence, and they didn't do everything right. But, she said, the evidence would show that they didn't do everything wrong.

Martin covered many of the same events described by Collier but made particular note of the complaints from BottleDrop that proceeded the shooting. These, she insinuated, were the result of BottleDrop's unwillingness to pay for the added security, with the location "constantly looking for reasons to complain about Cornerstone."

At the same time, Martin said, the complaints coming from TMT claimed that Cornerstone security guards weren't doing enough to crack down, culminating in the "zero tolerance policy." Internally, Martin said, Cornerstone had no intention of following that policy, citing regulations from the Oregon Department of Safety Standards and Training (DPSST) — the governing body for police and security guards alike — which require that guards give warnings and attempt to de-escalate tense encounters.

Martin then went into the circumstances under which Cornerstone hired Gimbel. While he had not been certified as an armed guard through DPSST, he was certified as an unarmed guard. Even then, Martin said, the state regulations allow unarmed guards to use force, make arrests and use pepper spray.

Gimbel passed a background check and did go through a legitimate training program to become an armed guard, Martin said. His understanding from the trainer for that program, Martin said, would have been that he did not have to wait to begin carrying a gun while working as a guard — as long as he passed his training and mailed off his documents to DPSST, he'd be fine to carry a gun while awaiting the official certification.

But 10 months after being hired by Cornerstone, Gimbel still did not have that official certification. And as the security firm struggled to adapt to the demands of the pandemic, Martin said, they did not check to see that he'd received it.

Partway through Martin's opening arguments, court was adjourned for the day. Arguments are expected to resume Friday.