PORTLAND, Ore. — On a cloudy afternoon in April, Officer Zachary Nell began his evening shift out of the Portland Police Bureau’s Central Precinct.

His first call brought him to a car crash in the Pearl District.

His second brought him to an apartment building off Northwest 21st Avenue, where residents had spotted a strange man in the building’s lobby.

They later found mailboxes had been pried open. The man was gone.

“That was coded as an unwanted person,” said Officer Nell afterward.

An unwanted person

Calls classified by that two-word phrase, "unwanted person," make up the bulk of Officer Nell’s workload, he said. Patterns emerging among 911 calls in the Portland area shed light on why.

First reported by Willamette Week, calls reporting an “unwanted person” have increased 60% since 2013.

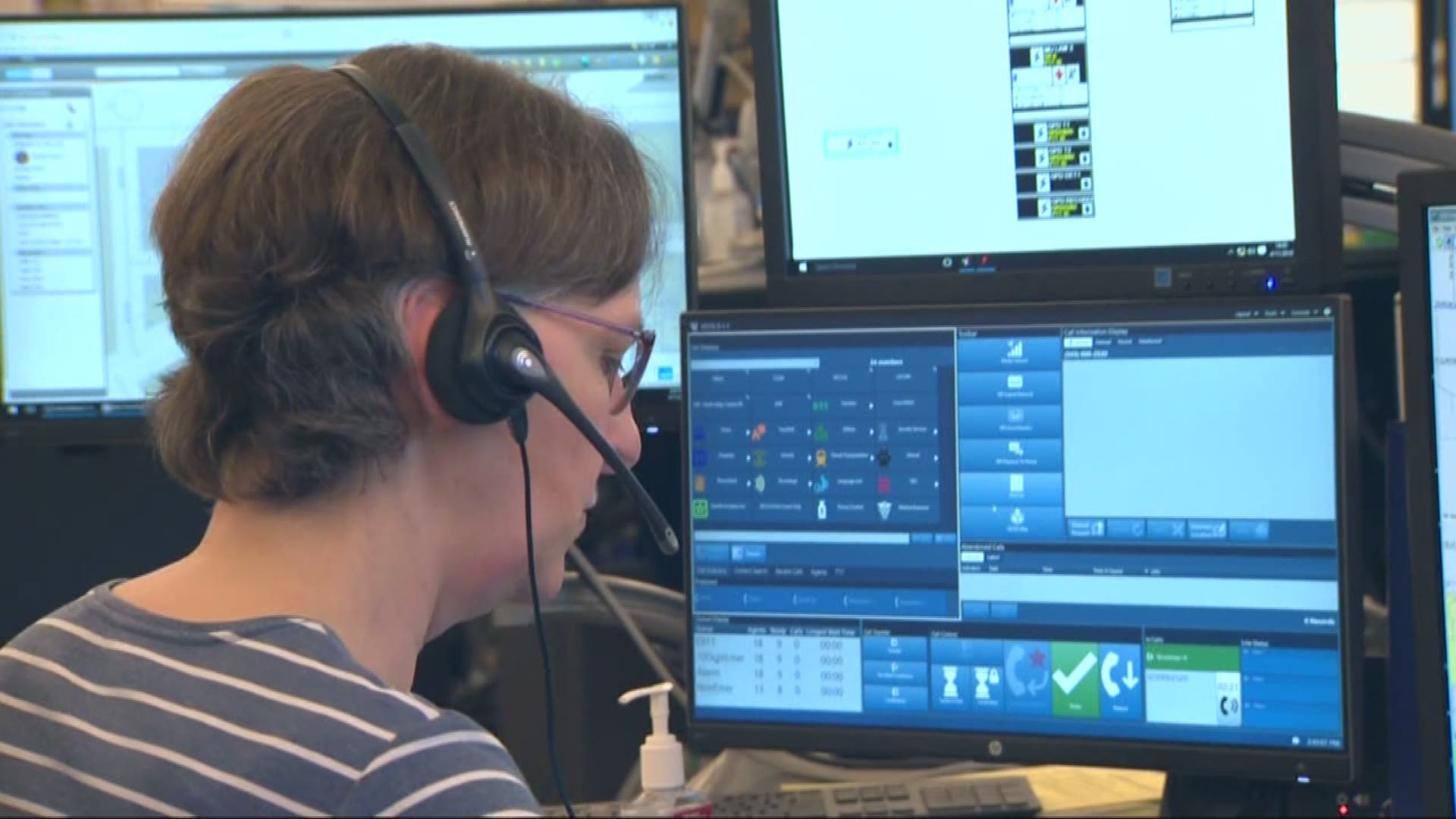

Anne Hamburg has been a voice on the other end of those calls for close to 30 years.

“I work day shift,” she said. “So a lot of times the employees are getting to work and seeing that they can’t get in the door because somebody’s set up their whole camp and sleeping right in the doorway.”

Often, she said, it boils down to complaints about homeless camps existing or someone acting strange. In those cases, when there’s no clear threat to safety, it can be tough to know whom to send.

“Sometimes a caller might be really insistent about wanting police,” Hamburg said.

Now they have another option, courtesy of the 2019-2020 Portland city budget, approved by the city council Thursday afternoon.

Portland Street Response

Following a multi-page editorial from Street Roots, Mayor Ted Wheeler answered calls for an alternative first-response option, setting aside $500,000 to fund a “Portland Street Response” program.

The idea is to, instead of police, send some combination of EMTs, mental health professionals and/or crisis counselors to 911 calls involving mental health or houseless people.

At a press conference earlier this month, the Mayor noted city leaders are allocating the money now, even though there’s no specific plan yet for how this program will work.

Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty, who runs the Bureau of Emergency Communications, is leading that effort.

Amid Portland’s housing crisis our current system wastes resources, she said.

“Many times the 911 call taker doesn't know who to send, so we may send everybody. Many calls, we send the police, we send the fire, we send the ambulance,” she said.

The city’s newest commissioner cited an argument pushed by Street Roots and homeless advocates: Police often aren’t the best fit when it comes to confronting someone in the midst of a mental health crisis, either because their approach, traditionally, can be too forceful or because the sight of an officer with a gun can scare someone not in their right mind.

She, like many in the advocacy community, points to the case of Andre Gladen, who was shot and killed by Portland police earlier this year.

Officers said Gladen, barefoot and paranoid, broke into a stranger’s apartment and, after police officers arrived, produced a knife.

His family said he was partially blind, schizophrenic and never violent.

Commissioner Hardesty believes police shouldn’t have been sent to his call in the first place.

“I don't have a medical degree but I know when you yell at somebody in a mental health crisis that agitates them more,” she said. “One life lost because somebody didn't do what they were told while they were in a mental health crisis is one life too many.”

So a few months back, Hardesty’s office kicked off an 18-month, $950,000 training program--covered by last year's budget--to re-tool how 911 operators receive calls and ask questions.

The strategy, dubbed the “Medical Priority Dispatch System”, is based on other models nationwide.

The goal will be to better judge when it’s necessary to send police officers, and when mental health professionals and EMT’s can suffice.

Those other options will, she points out, be funded by the 2019-2020 budget’s $500,000 allocation.

Commissioner Hardesty admits there are still a lot of questions about how that money will be spent.

“Are they city employees? Are they a combination of city and county employees? Are they private healthcare HMOs who want to be partners in this?”

To get some ideas, she, Mayor Wheeler, and several other city leaders have been heading about 100 miles south to visit a decades-old program that’s suddenly under a growing spotlight.

What Eugene is doing differently

No more than five minutes away from the University of Oregon’s campus, a small group of white vans sat outside an older, blue house, turned clinic and office space.

In the parking lot, two-person crews loaded up medical supplies as Tim Black looked on.

“It really seemed like a matter of time before Portland started to look for alternatives,” he said, laughing about the anticipated visits.

Black is the operations coordinator for CAHOOTS, or Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets.

The program, which started by running first aid tents at Grateful Dead shows in the late '70s and '80s, has worked alongside the Eugene Police Department for the past 30 years, helping field and process calls involving mental health, housing issues and all of the above.

“We also do, like, medical evals. People will call us out on the streets and say, ‘Hey, can you check my blood pressure for me?’ ‘Can you check my blood sugar for me?’ We do all sorts of things like that,” said EMT Daniel Murray. “We also respond to people who are like experiencing their first psychotic break.”

As housing crises loom and draw headlines across the country, attention on the program has ballooned.

On this random Wednesday afternoon in April, Black was fielding calls about future visits from public officials in California and Colorado, as well as a journalist from Al Jazeera.

A lot of the attention, he pointed out, stemmed from a November profile that ran in the Washington Post.

Black said he gets why so many cities are attracted to this alternative, which operates with 40 paid staff members, most of them full-time.

They have one van on the road 24/7 in Eugene. Soon, they’ll have a second one operating 18 hours a day, seven days a week. They also have one van operating 24/7 in a new, parallel program in Springfield.

CAHOOTS costs the city of Eugene approximately $1.2 million per year, said Black, adding estimates vary on how much the program saves the city in police staffing and overtime costs.

“It’s in the hundreds of thousands, if not millions of dollars,” he said. “Having a behavioral health first response, like the CAHOOTS model, can really act as a force multiplier because when we're responding that means that officers don't have to.”

They respond to more than 20,000 calls or service a year, he said, helping between 10,000 and 15,000 people

Lt. Carolyn Mason has worked with the Eugene police department for 20-plus years.

“They're able to go to calls for service that are really social-based problems and not really criminal justice problems," she said. "Whereas we would be responding and dealing with an intoxicated individual who needs to go to a shelter or a detox center. Takes time away from us going to more urgent calls, rescuing people.”

She also pointed out that Eugene’s 911 call center operates within the city’s police department.

Operators are trained to ask questions aimed at deciding whether a sending an officer is truly necessary. If there’s any ambiguity, they’ll often send an officer first to assess the risk factor.

If and when that officer decides the situation is safe, they’ll bring in CAHOOTS, which frees them up to leave the scene sooner than they otherwise would have.

Black said since the program’s founding in 1989, no staff member has ever been in a major traffic collision or suffered a major injury while responding to a call.

Lt. Mason has never worked as a police officer without CAHOOTS, and she wouldn’t want to.

“We’re very lucky,” she said.

Officers with the Portland Police Bureau, though, aren’t so sure.

Would it work in Portland?

It's a routine that makes far fewer headlines than responding to of-the-moment emergencies: Two teams, each made up of an officer and a mental health clinician, work five days a week, checking in on people suffering from apparent mental illness within the city of Portland.

They’re part the Portland Police Bureau’s Behavioral Health Unit, and they follow up on referrals from patrol officers.

“On average we get about 1,000 referrals per year that come in,” said Lt. Casey Hettman. “We may find an individual that's had frequent police contact and maybe their behavior has shown escalation over the recent days or weeks. That would be concerning to us. Obviously, any time there's a weapon or a perceived weapon involved, that's concerning.”

Lt. Hettman runs the BHU, which also helps coordinate a separate partnership with Cascadia Behavioral Health, allowing officers 24/7 access to emergency health clinicians. If and when they want one to respond to a call with them, they can call.

“We do have a number of other things in place that serve individuals with mental health concerns,” said Lt. Hettman.

The strides are among several made by the bureau in recent years, following a 2013 ruling from the U.S. Justice Department that found PPB had a pattern of using excessive force against people suffering from mental illness.

Now all 900-plus PPB officers undergo 40 hours of crisis intervention training, which covers things like talking to someone in a mental health crisis or responding to suicidal threats.

Close to 130 of them have undergone 80 hours of enhanced crisis intervention training. They’re among a team of specialized officers and negotiators sent to calls where someone is in the midst of an immediate mental health crisis.

“Some of these people who are going through a mental health crisis will sometimes be more comfortable speaking to a police officer than they will a social worker or a clinician,” said Officer Zachary Nell.

Officer Nell voiced the same concern highlighted by other members of the Bureau: Portland is a bigger city than Eugene with a larger, more urban homeless population.

They worry about unarmed citizens being sent to calls that seem benign at first but then turn violent. Officer Nell said in his experience, the sight of a universally recognizable authority figure sometimes calms people down.

“I've come across that before where I’ve worked with somebody who is in mental health," he said. "I had a bigger conversation with that person myself because they felt in their mind I would make more of a change.”