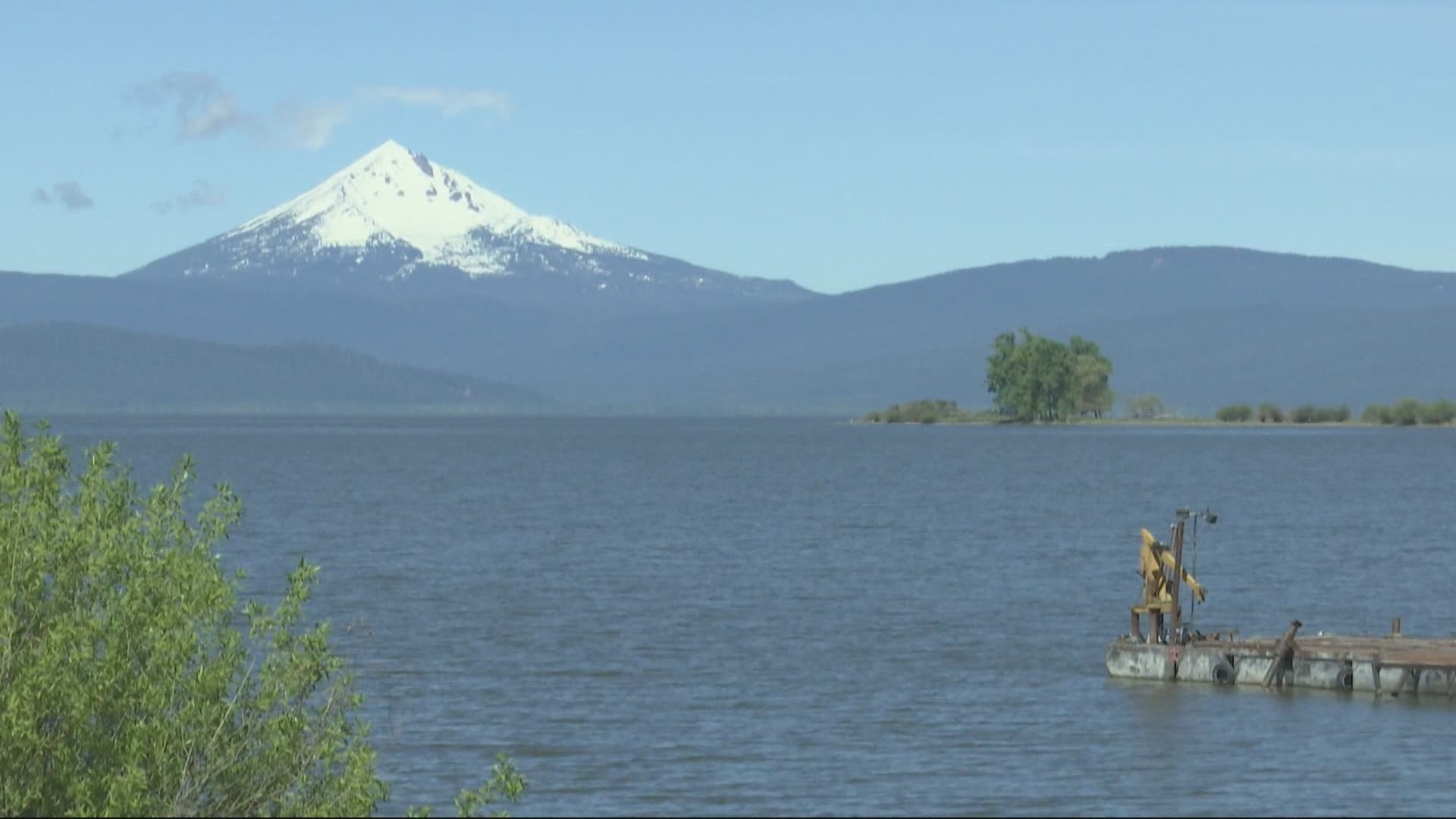

PORTLAND, Oregon — A severe drought in southern Oregon is leading to a crisis for many farmers in the Klamath Basin.

The basin stretches over 12,000 square miles in southern Oregon and northern California. It is home to farmlands that were marshes until the early 1900s.

The lake supplies irrigation water, which is controlled by the federal government's Bureau of Reclamation. But it’s also the source of water that endangered fish need to survive and Native American tribes need as well.

This year, the federal Bureau of Reclamation said there is not enough water and announced the farmers will get nothing in an effort to save the endangered fish, infuriating some.

“Pretty soon we’re gonna get this water flowin',” said farmer Dan Nielson as he stood by a chain-link fence near a main irrigation canal. “One way or another this water is gonna flow this year. We’re not gonna let the government steal our water."

He and another farmer bought a small plot of land right next to something called the "headgate," which controls the flow of irrigation water out of the lake.

Right now, it's closed and the canal the water would flow through is blocked with massive concrete slabs that would stop most of the water even if someone did open the headgate.

Local newspaper reporter Alex Schwartz said most farmers do not want the headgate forced open.

“The majority of farmers in the project don’t support the action that these folks at the headgate plan to take. They don’t support trespassing on government property or removing the headgates,” he said.

Schwartz works for the Herald and News out of Klamath Falls.

For the past year, he's covered the drought and irrigation water. He said many farmers see the threats to force the water to flow as a distraction.

“They believe it’s not going to actually help them this year. It’s not going to get them any additional water, cause a lot of crops have already been planted on the basis of somebody has well water or some districts are still able to divert some surface water from other places,” he said.

There is no question many farmers are being financially hurt by the lack of water.

It’s likely worse than the shortage of 2001, which saw tens of thousands arrive in the area to help with a bucket brigade. Protesters literally took buckets of water from the lake to pour into the irrigation canal. Eventually, some water did flow but it was a fraction of the normal amount and later in the summer.

A report to Congress shortly after the 2001 crisis noted farmers at the time estimated losses at between $160,000,000 and $222,000,000.

So far the federal government has offered $18,000,000 to help the current situation and congressman Cliff Benz, who represents the area, wants another $57,000,000 for farmers.

Governor Kate Brown declared the basin a drought emergency area on April 14.

“My heart goes out to the people of the Klamath basin,” she said last week.

Governor Brown visited the area 20 years ago as a state lawmaker when the bucket brigade took place. Now she is asking for calm.

“I want to encourage everyone to keep their efforts peaceful and to let them know that we are doing everything we can to get resources there to assist,” she said.

But tensions seem to be mounting because of one name.

“I think a lot of the reason folks outside of the basin are being attracted to this now is because of the potential for the Bundys to get involved,” said reporter Alex Schwartz.

Ammon Bundy led the takeover at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Harney County in 2016, then beat federal charges connected to the takeover.

Bundy has not shown up in the Klamath Basin, but his supporters say he's offered to if needed.

In the meantime, farmer Dan Nielson and others set up a big red and white striped tent to hold rallies and spread interest.

It’s also why he bought that property so close to the irrigation headgate.

“It’s kind of an investment property for us. We just bought it for a little investment and set this camp up to keep people from trying to run us off,” he said.

Have a comment or story idea for Pat Dooris? Email him at pdooris@kgw.com