‘Completely derailed our life’: How child care in Oregon became so unaffordable

A single mother in Portland moved into a homeless shelter with four children after losing state-funded child care because her income crossed over the line by $2,000.

With average child care costs in Oregon as high as rent — families statewide have felt the strain — and left some struggling with what to do.

“It keeps them from going to school, and it makes them have to make some hard decisions between paying the rent and paying for child care or paying for food,” said Candace Vickers, director of Family Forward Oregon, a nonprofit part of Child Care for Oregon lobbying for universal child care.

Natalie Kiyah, a single mother of four in Portland, is one of those parents. In 2023, after losing child care support through Oregon’s Employment Related Daycare Program (ERDC), Kiyah checked herself and her three kids, while pregnant, into a family homeless center because she could no longer afford rent.

“That completely derailed our life and our family stability,” Kiyah said.

KGW surveyed over 40 care centers in the Portland metro area in March and found that tuition costs for infants and toddlers averaged $1,167 for part-time care to $1,680 a month for full-time care, while child care costs for preschool-aged children can range from $895 part-time to $1,325 full-time.

“If you think about that, in Portland, that's as much as rent, that's as much as your tuition for one of our state colleges,” Vickers said. “That's a lot of money."

Searching for child care

Kiyah went from having child care access and full-time support, which allowed her to grow her photography business, to having none of it overnight.

In March 2023, she received an “exit letter” from the state because her annual income had crossed over the salary cap for ERDC program by $2,000.

To qualify for ERDC, families must either be working, in school or receiving aid from the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. It has set income limits for how much a family can earn before they no longer qualify. The income limits often increase each year. For 2024:

- Families of three can earn no more than $76,500 ($6,375 monthly)

- Families of four can earn no more than $91,068 ($7,589 monthly)

- Families of five can earn no more than $105,636 ($8,803 monthly)

Prior to Kiyah being kicked off ERDC, she was receiving a stipend of $1,600 per month to send her son to preschool, while her two elementary-aged children attend a Portland public school. For a couple of months, she tried to cover the child care costs on her credit card, but with that and rent, the expenses were piling up.

“I was kicked off ERDC and that was debilitating for our family,” Kiyah said. “We could not pay rent; I couldn’t pay bills. So, I ended up making the decision — well, I had no other option — I moved into a family homeless shelter to attempt to regain stability.”

After her daughter was born, and once at the family homeless shelter, Kiyah switched jobs from doing solely self-employed work at home to a position at the Oregon Food Bank that allowed her to requalify for the ERDC program.

Currently, ERDC covers 100% of Kiyah’s daycare needs, which now exceeds $3,000 per month. It provides infant care for her daughter, preschool for her son and after school care for her second graders. Without the stipend, she said child care would cost 75% of her monthly take-home paycheck.

While at the family homeless shelter, Kiyah learned that she’s not alone.

“I am not the only one whose life has been derailed by losing child care or not having access to it,” she said.

Compared to other states, child care costs in Oregon are among the most expensive in the U.S. In 2023, the Annie E. Foundation, a charitable organization centered on children’s well-being, found Oregon ranked in the top 15 of states with high child care costs. Last year, Oregon families spent on average $13,000 on child care, and around 15% of Oregon families had to make job changes due to child care problems.

Vickers said that in many cases, a family member will leave work and choose to stay home because that’s the only way they can afford child care.

But for single parents like Kiyah, there aren’t many options other than finding child care so she can work.

“I was really thinking after 2023, we’re going to be able to buy a house,” Kiyah said. “But then I ended up being homeless. It was quite the juxtaposition.”

Creating Barriers

The cost of child care is a huge barrier, Vickers said.

"The care economy touches every single part of our economy,” she added. “The care economy is the thing that underskirts everything else that works about our state.”

But rather than helping, the ability for families to find and afford child care have been deepening disparities that the state has been trying to fix, like the housing crisis and labor shortage, while also exacerbating the wealth gap.

Audreona Mullens, a mother in Portland, said her and her husband were jubilated when her son was born. Once he turned 2 years old, Mullens said her family could finally afford to send her son to daycare, but even then, just part-time.

“That happiness was definitely something that we weren’t necessarily fully informed, and fully prepared for the realities of having a child that needed to be in daycare,” she said.

Still, with her son in daycare, Mullens was also able to return to work part-time with a job at Family Forward after staying home for two years. Coming back, she said, really helped her mental health, as she always connected working hard in her career as part of her identity.

But, by only being able to be part-time, Mullens said that her whole paycheck went toward covering the cost of her son’s daycare — leaving little to no room for her family to grow financially.

“Seeing the cost of child care immediately let me know and understand that this is going to be an uphill battle,” she said. “I don’t know how much of this is going to be something that I can mitigate."

When her second child was born, Mullens said they had to move in with her husband’s parents to then afford the costs of a newborn and for her son to be in part-time daycare. This also allowed them to save money to afford a house again.

“Thankfully, when Preschool For All was introduced, my son was able to get a spot,” Mullens said.

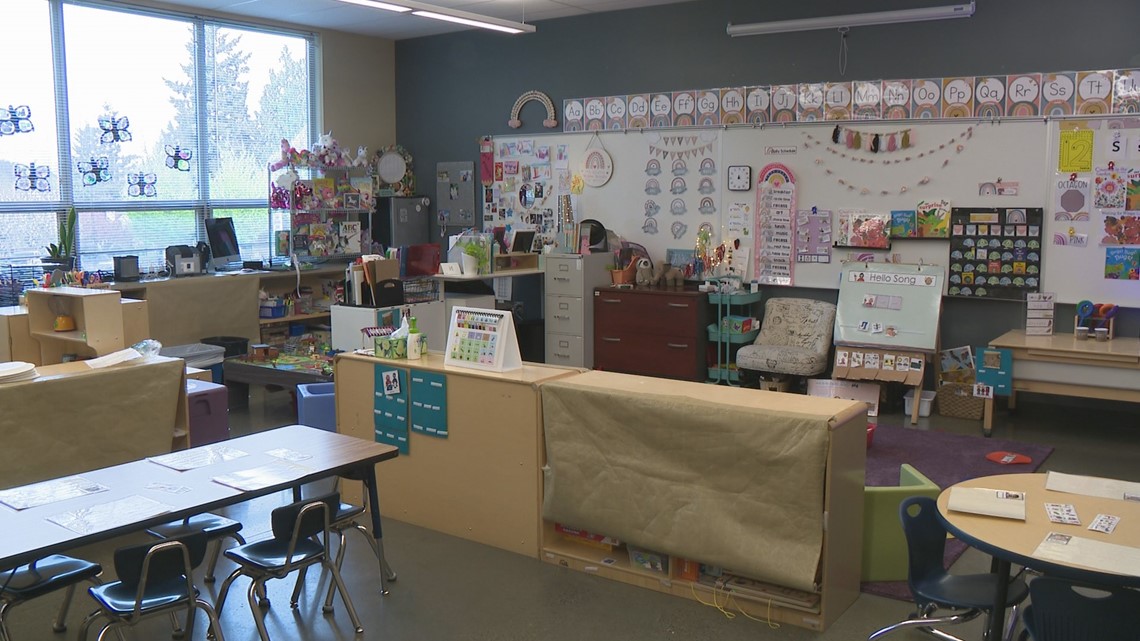

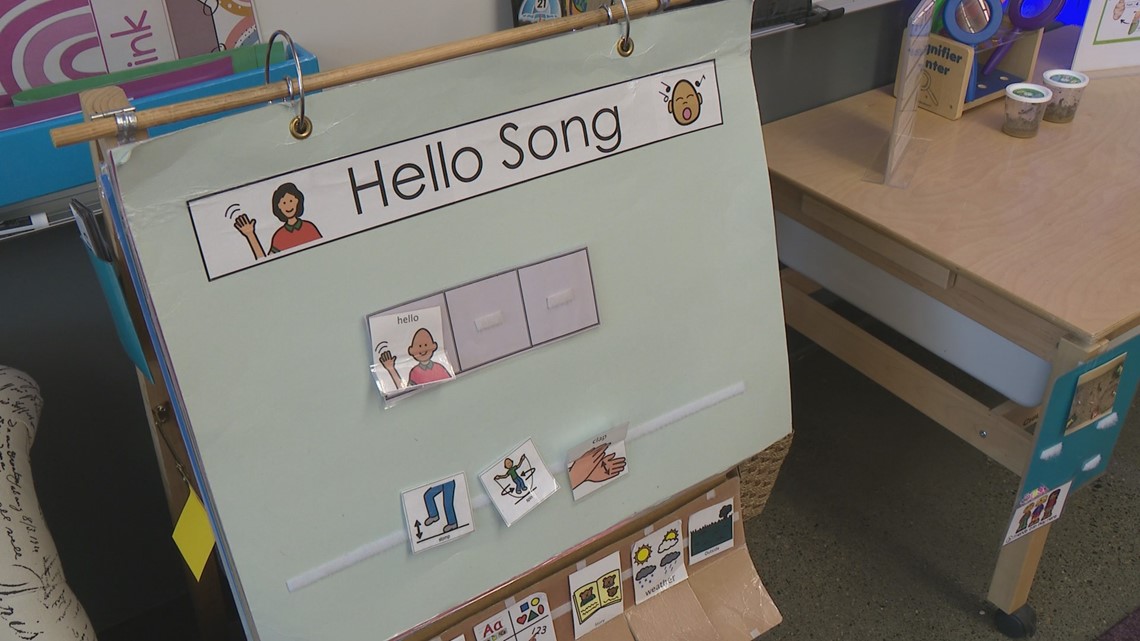

The Multnomah County-led program, approved by voters in 2020, started to offer free preschool to three-and four-year-olds. So far, it has supplied free child care to nearly 1,400 children in Multnomah County.

Mullens said when her son was able to get a spot, it allowed her to go back to work full-time and for her family to grow their financial well-being.

Preschool For All’s goal is to create 11,000 publicly funded slots by 2030. But despite the program’s growing pains, Mullens said without it, she would have still been paying an exponential amount of their income toward child care.

“I think you’ll find that it is a universal experience when you are looking for child care,” Mullens said. “The realities of finding child care and affording child care ... it’s a struggle for almost anyone.”

How did child care get so expensive?

Oregon is a child care desert where there are more children that need care than spots available. One-sixth of infants and toddlers in Oregon have access to child care, and about one-third of preschool children are also left waiting for an available spot, according to an Oregon State University (OSU) study.

Almost all Oregon counties are considered child care deserts for infants and toddler care (0-2-years-old). And without publicly funded slots through programs, like ERDC and Preschool For All, all Oregon counties, except three, would be considered child care deserts for preschool care.

While the state’s child care network has been broken for a while, the COVID-19 pandemic made it worse. The child care industry is seeing a depleting field of workers who are leaving due to exhaustion or in search of higher pay.

In Multnomah County, the decrease was substantial. Multnomah County Chair Jessica Vega Pederson said the county lost about a quarter of its child care capacity during COVID-19, deepening the region’s child care gap.

While some private facilities have found success, others often work on thin profit margins and can struggle with the high costs that come with providing child care: staff.

For safety, the state requires a certain number of care-staff-to-child ratios for businesses certified or licensed to be child care providers. This leaves little to no flexibility on labor costs for providers, other than paying the minimum and employing the minimum number of staff needed.

According to the OSU study, staffing can account for more than 80% of provider costs.

In Oregon, providers are required to maintain a 1:4 caregiver ratio for infants, 1:5 for toddlers and 1:10 for preschool. There are also restrictions on how large the groups of children can be.

So it’s no wonder that providers struggle to find staff or why early-learning educators may leave for a higher salary.

Where some providers might make up costs is with additional child care expenses for parents, ranging from enrollment fees, material fees, waitlist fees and late fees for pick-up. This can typically add at least $170 to families’ annual child care costs, based on the care centers KGW surveyed.

This is why Vickers has been lobbying for universal child care and why programs like Preschool For All have been granting subsidies to providers rather than directly to parents, in the hopes of creating sustainable child care solutions.

“There’s been a lot of concern about a decrease in birthrate,” Vickers said. "We have to recognize that families are making a decision between having another child or being able to feed the children that they have.”